![]()

CHAPTER 1

Translating the Language of Architecture

PETER BURKE

One of the major shifts in cultural history in the last generation, as indeed in economic history, has been the inclusion of consumption alongside production. The new emphasis on consumers of culture treats them not as passive receivers but as active “reemployers” and as makers of meaning. Literary historians now study readers as well as writers; musicologists study listeners as well as composers and performers; historians of art and architecture study clients and viewers as well as artists; and theorists of reception offer generalizations about all these processes, shifting attention away from the individual creator and examining collective processes of transmission that often involve changes of meaning, linked to the consumers’ horizons of expectations.1 It is therefore no surprise to see a rise of interest in the history of translation.

In the case of the Renaissance (a term used here to refer to a movement rather than a period), an academic interest in the reception of Roman law and of humanism goes back to the later nineteenth century.2 As his collected works show, the central enterprise of the scholarly life of Aby Warburg was the way in which the classical tradition was received and transformed over the centuries, especially but not exclusively in the realm of visual culture.3

All the same, it is only recently that reception has become a major theme in the study of the Renaissance, especially in the case of literature, often focusing on individual writers or their books.4 General interpretations of the Renaissance outside Italy have also been paying more attention to the question of reception.5 The proliferation of studies in the history of reading is a move in the same direction. Terms such as “cultural transfer” and “cultural exchange” are coming into increasingly frequent use to refer to the past as well as the present. For example, they underpinned a recent collective project on the cultural history of early modern Europe, planned by the French historian Robert Muchembled and financed by the European Science Foundation.6

A related concept, which is coming to show its usefulness, is that of “cultural translation.” This phrase was originally used by British anthropologists such as Edward Evans-Pritchard to describe their own attempts to interpret to a public in their own society the cultures that they had studied in Africa, Oceania, and elsewhere. They tried to present the customs and beliefs of the Azande or the Trobrianders, for instance, in ways that would be intelligible to Western readers.7 Like anthropologists, historians may be regarded as translators, in their case from the language of the past into that of the present, facing the same basic dilemma as translators between languages—in other words, the conflict between fidelity to the culture from which they are translating and intelligibility to the audience at whom their work is aimed. More generally still, anyone who adapts ideas or artifacts to new situations and new uses, as so often happened in the course of the Renaissance, might be described a cultural translator. It should be added that translation in the literal or interlingual sense may be regarded as a kind of litmus paper that makes the process of cultural translation more visible than usual.8

What follows is concerned with translation in both senses, literal and metaphorical. It retells a small part of the story of the reception of the Renaissance, moving backward and forward between the translation of texts and the translation of artifacts, between the idea of transfer and the idea of translation (words derived from the same irregular Latin verb, transferre, transtuli, translatum). Indeed, some sixteenth-century translators such as Hermann Ryff, discussed in what follows, described themselves as “transferring” a text from one language to another.

The case study presented here concerns the “language of architecture,” as Sir John Summerson and other scholars have called it.9 The metaphor is actually an ancient one, since Doric and Ionic were the names of Greek dialects before the terms were applied to forms of columns. The shift from the Gothic style to the revived classicism of the Renaissance may be seen as a change in architectural language, both in the vocabulary of ornament and in what we might call its “grammar,” in other words, the rules for combining different elements.

For the transition from Gothic to Renaissance to take place, the physical transfer of artists and artisans was surely a necessity. It has been persuasively argued by some economic historians and also by some historians of science that “through the ages, the main channel for the diffusion of innovation has been the migration of people,” and that “the transfer of really valuable knowledge from country to country or from institution to institution cannot be easily achieved by the transport of letters, journals and books [or indeed, one might add, works of art]: it necessitates the physical movement of human beings.” In short, “ideas move around inside people.”10 The point is surely even more valid in the case of practical know-how than in that of more theoretical knowledge. A “habitus,” as Pierre Bourdieu (following Aristotle via Thomas Aquinas and Erwin Panofsky) called it, requires personal encounters in order to be transferred effectively.11

In the case of Renaissance architecture, these encounters are quite well documented, revealing the central role played by Italian artisans, especially masons from the Lake Como region, in the construction of Italianate buildings in France, Bohemia, and Poland.12 Conversely, the travels in Italy of foreign architects such as Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, Philibert Delorme, John Shute, and Inigo Jones had important cultural consequences. What they saw and learned in Rome in particular shaped the work of these architects for the rest of their lives.

Even if people come first, as suggested earlier, the migration or transfer of texts was also crucial in the reception of the Renaissance. Hence what follows will attempt to combine the history of architecture with the history of the book. As a number of scholars, notably Don McKenzie, Gérard Genette, and Roger Chartier, have pointed out, the format of a book, including so-called paratexts such as prefaces, headings, indexes, and illustrations, is almost as influential in terms of a book’s reception as the text itself.13 Following their example, it is possible to trace the history of a whole shelf of architectural treatises as they were written, printed, reprinted, edited, translated, studied, annotated, borrowed, or imitated.14

The only surviving classical treatise, written by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio around the year 27 BCE, was rediscovered in the age of Charlemagne, and circulated in manuscript, sometimes in incomplete form, in the Middle Ages. It was known to medieval scholars such as Hugh of St. Victor and Albertus Magnus as well as to Petrarch and Boccaccio. In 1416, the Tuscan humanist Gianfrancesco Poggio Bracciolini found a complete text in Switzerland, at the monastery of Sankt Gallen. The text was printed for the first time in the 1480s and many times thereafter.15 (See Figures 2 through 6.)

Another leading Italian humanist, Leon Battista Alberti, both criticized and imitated Vitruvius in the first Renaissance treatise on architecture, written mainly in the 1430s and presented to Pope Nicholas V around the year 1450. Like Vitruvius’s work, Alberti’s De re aedificatoria was first printed in the 1480s.16 Together, Vitruvius and Alberti inspired a new genre that laid down the rules for proper building just as Pietro Bembo and other humanists had laid down the rules for writing well. Examples of this new genre included the following:

Diego de Sagredo, Medidas del Romano, 1526

Sebastiano Serlio, Sette libri dell’architettura, 1537–

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, Livre d’architecture, 1559

Philibert Delorme, Nouvelles Inventions, 1561

Giacomo Barozzi de Vignola, Regola delli cinque ordini

d’architettura, 1562

John Shute, Grounds of Architecture, 1563

Jean Bullant, Reigle générale d’architecture, 1564

Andrea Palladio, Quattro libri dell’architettura, 1570

Hans Vredeman de Vries, Architectura, 1578

Wendel Dietterlin, Architectura, 1593–

Vincenzo Scamozzi, Idea dell’architettura universale, 1615

Henry Wotton, Elements of Architecture, 1624

Today, the most famous of these treatises is surely Palladio’s. However, Serlio’s was by far the most widely read at the time, translated into Flemish, German, French, Spanish, Latin, and finally, in 1611, into English. He probably owed his popularity to his clear, down-to-earth style, together with his interest in ornament, which—helped by the numerous illustrations—made it possible to use the treatise as a pattern book.

The treatises were usually prescriptive as well as descriptive. For this reason Serlio entitled his fourth book Regole generali, Vignola and Bullant entitled their treatises Regole delli cinque ordini and Reigle générale d’architecture, while Scamozzi’s book 6 was translated into Dutch under the title Grondregulen der Bow-Const (1640).

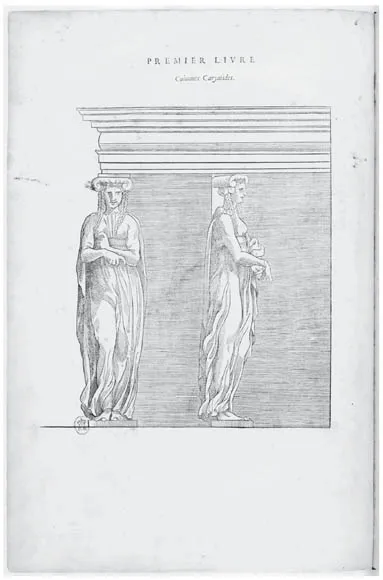

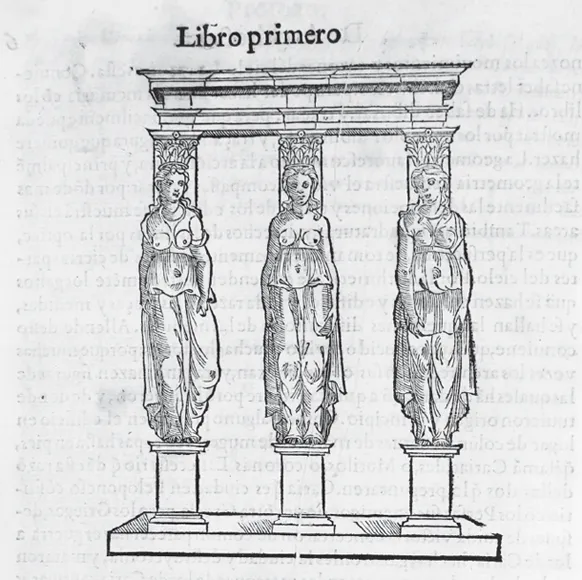

Figure 2. Caryatids, in Architecture, ou Art de bien bastir. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, 1547. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

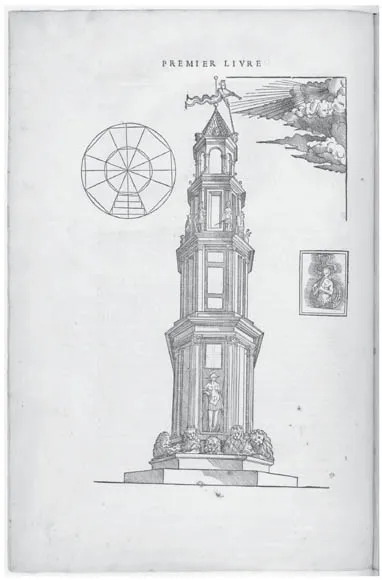

Figure 3. Tower, in Architecture, ou Art de bien bastir. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, 1547. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

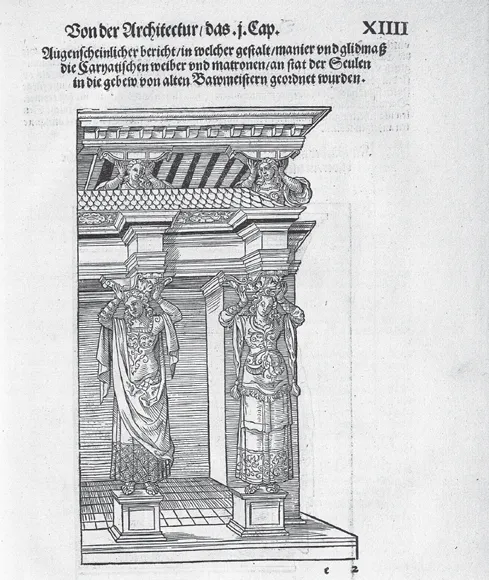

Figure 4. Caryatids, in Vitruvius Teutsch. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, 1548. Universität Heidelberg.

The fact that Vitruvius was difficult to interpret needs to be emphasized. The dedications to the two Italian translations of Alberti refer to “gli oscuri scritti di Vitruvio” and note that the text is “molto difficile e oscuro.”17 The French sculptor-architect Jean Goujon noted that misunderstandings of the text had led to what he called “oeuvres . . . desmesurées, et hors de toute symetrie.”18 It is therefore no surprise to discover that the treatise generated an abundant literature of commentary. In the case of the Italian translation of 1521, for example, each page of the text of Vitruvius is completely surrounded by a commentary in smaller type. The French humanist Guillaume Philandrier published another commentary on Vitruvius, and so did the Venetian patrician Daniele Barbaro.19 The Italian humanist Bernardino Baldi devoted a treatise to elucidating the vocabulary of De architectura.20

Figure 5. Caryatids, in De Architectura. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, 1582. Universidad de Sevilla.

The importance of these texts for the reception of th...