![]()

PART I

Life Under Siege

![]()

Chapter 1

Civilian, Soldier, Deserter

How can people who have never experienced war understand what it is like to live in a city under siege in a state that has disintegrated into warring national armies? The terror aroused by the constant threat to life is intensified by the disruption of everyday existence that living in a war zone entails. Most of us have experienced a similar kind of shock on a smaller scale. Our first confrontation with the death of a person close to us, a disastrous accident with casualties whose faces we recognize, or a natural catastrophe in the place we call home—experiences of devastating loss seem incomprehensible and make us feel powerless. The world as we knew it has been destroyed. With no satisfactory way of dealing with this unprecedented existential situation, we question our previous faith in the orderliness of the world and the social norms that had governed our lives up to that point. This feeling of disorientation is not necessarily harmful in itself; indeed, it might even be necessary for the process of mourning that we must undergo to reorient ourselves to a new reality. War is like other experiences of devastating loss, but with two crucial differences: the losses are caused by fellow human beings, and we can never reorient ourselves completely to the new existential reality. Time after time, as the violence of war inflicts new losses, we are overwhelmed by the incomprehensibility of the situation and our powerlessness within it. As Michael Taussig puts it, we find ourselves swinging wildly between “terror as usual” and shock (1992:17–18). When the agents of death and chaos are not impersonal forces but other people, former compatriots, and even neighbors, who suddenly bring destruction down upon us, the situation is even more profoundly unsettling. The faith in humanity on which society itself is founded is constantly undermined, and every action we take to try to save ourselves seems trivial or pointless.

In this light, some of the most shocking experiences of loss and disorientation in our peacetime lives in Europe and America resemble wartime experiences. Deaths caused by criminal gang violence in the inner cities and by terrorist attacks in New York City, London, and Madrid—as well as the “peacekeeping operations” that the United States, NATO, and the United Nations conduct in African countries and the ongoing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—are all caused by people, yet they are incomprehensible and out of control. In these circumstances, we react in ways that are similar to those of people caught up in war. This resemblance makes the experiences of people in Sarajevo during the siege of much more profound interest to us than we would have expected.

Both the immediate experiences that being caught up in war entails and the moral dilemmas that arise when struggling to survive in a city under siege make untenable the notion that wars are rational, controlled, sometimes even honorable, ordered and limited by the laws of war, with legitimate aims and clearly distinct opposing sides—a notion that still dominates the practice of international politics.1 Almost without exception, whether conflict rages across international borders or attempts to impose new boundaries between peoples, war is gruesomely devoid of logic. Perhaps that is why fiction and film seem to capture wartime realities more powerfully than journalistic accounts and expert analyses. The moral unacceptability of “the laws of war” becomes appallingly clear when we examine the terminology designed to disguise the more ghastly rules of war: “collateral damage,” “low-intensity conflict,” and “ethnic cleansing” are among the euphemisms that obscure killing, starvation, and displacement. War legitimizes mass murder and destruction of property, which no other legal system allows on such a scale within such a short period of time.2

By trying to find the causes and logic of war—often in hope of understanding it and being able to control the damage it inflicts, if not stop or prevent it in future—we unavoidably fall into reifying the divisions into distinct warring sides, with their aims and justifications for mass violence. Such was the case with many expert analyses of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also with many Sarajevans in their attempts to orient themselves in chaotic life circumstances and to justify their often morally ambiguous practices. In order to avoid the pitfalls of oversimplifying war and ignoring its incomprehensible, unjustifiable, and unacceptable nature, I chose to let individuals’ lived experiences of violence stand at the center of research and from that point to trace the effects of war on society and culture.3 This account explores Sarajevans’ subjective responses to the death and destruction that engulfed their city and their repeated, though often futile, efforts to make sense of the disturbing and irrational situations in which they found themselves.

After struggling to orient myself in the midst of chaotic and contradictory experiences, I realized that these feelings and ideas could be sorted into three different modes of perceiving war. At first, people are so struck by the outbreak of a war they had thought impossible that the social norms they had thought secure collapse. I call this initial disbelief and the vacuum of meanings that follows the “civilian” mode of perceiving war. Then people attempt to order and explain the events and actors, adopting what I call the “soldier” mode. Aligning themselves with one or another of the warring sides, they seek protection and solidarity, giving some meaning to the risks they must face. The soldier mode offers a moral rationale for conflict, making the destruction and killing seem necessary and even acceptable. Finally, people realize through their own experiences of war that these explanations do not hold and shift to a third standpoint that I call the “deserter” mode.4 Abandoning the neat divisions between citizens and armies, friends and foes that mark the civilian and soldier modes, people give up allegiances to any opposing side and take responsibility for their own actions. This stance does not constitute treason or betrayal but expresses profound skepticism about the high ideals that justify vicious acts and an effort to recover some small measure of humanity in a world gone berserk.

These modes of feeling and thinking are not necessarily sequential or mutually exclusive; often people hold them simultaneously or shift back and forth between them as their situation changes. Everyone caught up in a war, or dealing with war as a journalist, diplomat, or researcher, employs all three of these perspectives. The inconsistencies in perceptions of war that are characteristic of those who are subjected to it involuntarily arise not only from war’s chaotic character but also from the best efforts to come to terms with it.

Imitation of Normal Life

As I focused on the experience of violence, I listened closely to what preoccupied my informants and how they spoke about everyday concerns. I noticed that people in Sarajevo often used the concept of normality to describe some situation, person, or way of life. The concept carried a moral charge, a positive sense of what was good, right, or desirable: a “normal life” was a description of how people wanted to live; a “normal person” thought and did things that were regarded as acceptable. The term pertained not only to the way of life people felt they had lost but also to a moral framework that might guide their actions. Normality not only communicated the social norms held by the person using it but also indicated her or his ideological position. The preoccupation with normality reflected Sarajevans’ utmost fear and their utmost shame: that in coping with the inhumane conditions of war, they had also become dehumanized and that they might be surviving only by means they would previously have rejected as immoral. Had they become psychologically, socially, and culturally unfit to live among decent people?

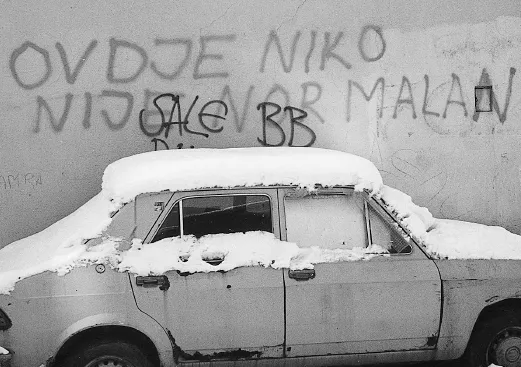

Figure 1. In 1995 graffiti appeared saying: “Nobody here is normal” (“Ovdje niko nije normalan”). Sarajevo, spring 1996. Photo by author.

Social norms are always in flux. Each person continuously defines and redefines his or her norms of conduct and perceptions of society in accordance with his or her daily experiences. In the context of war, the wholesale destruction of people’s homes, the intensity of chaotic feelings, and the constant demand to respond to unprecedented conditions make the pace and scope of change so dramatic that it is more easily noticed than in peacetime. I found it useful to follow the process of change in perceptions of normality in order to understand and explain people’s experiences of war in Sarajevo.

Schematically, change can be described as a process that occurs again and again:

• A norm exists.

• Violence disrupts normality; the norm does not hold anymore.

• Chaos reigns—a vacuum of meaning, disorientation, and normlessness.

• New truths compete to fill this vacuum: political ideologies, media interpretations, social contacts, rumors, and individuals’ own experiences.

• A new norm emerges, but it too is disrupted as the cycle continues.

Massive political violence disrupts the way we know the world works in peacetime and makes it worthless for orienting ourselves in a war zone. We feel plunged into a state of chaos, yet we are forced to take action in response to constant emergencies. What we previously found meaningful has been shattered, vanished, or become impossible, even inconceivable. As we struggle to make some sense of our situation, we seek desperately to fill this vacuum with new meanings. At this point, differing interpretations of the conflict compete for our allegiance. These contesting truths are promulgated by politicomilitary organizations and power elites; they are manufactured or propagated by the media, whether politically controlled or independent; they arise and circulate within our social circles, often in the form of rumors; and they come from our own desperate efforts to make sense of our disparate personal experiences. Amid a dizzying variety of interpretations, we settle on whatever seems to us the most useful guide to action and a notion of the world we can live with. On this basis, we join with like-minded and similarly situated others to develop a new norm, however provisional. But the cycle is repeated as new experiences fracture whatever tentative certainty and fragile consensus has been attained. The process continues on all levels of our lives, from the most existential through the material to the ideological.

Two examples illuminate this process. The first highlights how perceptions of normality changed on the most basic material level. A young woman, a doctor of medicine who became a friend, told me a story from the first months of war, when most Sarajevans were still reasoning within their peacetime standards. She and a friend of hers were going to a party one Saturday evening. As parties were very rare at that time, they fixed themselves up the best they could. Her friend even put on nylon stockings, which were already a scarce commodity. As they walked, the shelling started, and the explosions were very near. My acquaintance threw herself into the nearest ditch and shouted at her friend, who was still standing in the street, to do the same. The bewildered girl shouted that she could not because her nylon stockings would get torn. “To hell with your nylon stockings,” replied my acquaintance, “It is your head that will get blown off if you don’t get down immediately.”

The second example illustrates the changes in the relations between neighbors who belonged to different ethnoreligious and national groups and in the moral values attached to these relations. It was told to me by my host, a middle-aged man and an avowed anti-nationalist from a Muslim family background. At the height of the war, now and then he helped an old lady in the neighborhood by fetching water for her. It started one day when he saw her at her window and offered his help. After that she would sometimes wait for him with her canisters. One day a man in the street, presumably a neighbor who knew the old lady, commented, “Oh, you Serbs always stick together.” My host froze and told him his name, which was Muslim. “I think the man was ashamed,” he commented when he told me the story. As my host saw the situation, he was doing his neighborly duty. The man misinterpreted this solidarity in ethnoreligious terms, because the meanings of neighborliness and national identity were being renegotiated in the new atmosphere of rumors and media reporting of betrayal, or at least the lack of neighborly protection across national lines.

In peacetime, most people perceive normality as a stable, taken-for-granted state. Indeed, an essentialist conviction that this is how things really are seems central to our feeling of security, and discovering that nothing can be trusted anymore is almost as unsettling as the immediate dangers of living in a war zone. Political actors can exploit people’s need for security to promote their own versions of reality, and consequently those with more power have more to say about what normality is. However, even in wartime people do not automatically accept new explanations, ideas, and norms. It is more accurate to say that the redefinition of normality takes place in a political space where the power to define the truth is highly contested.

Characteristically, during the siege of Sarajevo, as in other situations of war, occupation, and captivity, powerful feelings of shame followed each breach and fall of a cherished social norm, while feelings of pride were associated with every solution to a predicament or resolution of a dilemma that created a new meaning in daily life. Yet even resourcefulness and resilience did not break the cycle. There were ways of escaping it, either by disconnecting psychologically or by fleeing. The local term for the emotional numbness and irrationality that followed an excess of pain was prolupati.5 People I saw who simply stood in open places during the shelling as if nothing was going on, or an elderly man with a distant look who was not interested in joining the rest of his family in their summer house in a peaceful part of coastal Croatia, might have escaped the exhausting circle of constantly reestablishing some sort of normality, but the price was the loss of all meaning. They lost contact with their feelings, including the fear necessary for physical survival and the need for closeness necessary for emotional survival. They were the zombies of the war. Refugees who escaped from the physical perils of war found very quickly that escape did not free them from a need to come to terms with the politics of national belonging, the violence they had witnessed and evaded, and their decision to leave while others remained, with all that that meant materially, socially, and morally.

Each and every turning in this spiral of shattered and re-created norms was marked by a movement between some semblance of normality and the eruption of chaos. People who could easily give me a sophisticated political analysis one day would the very next day express bewilderment and ask me to explain to them why all this was happening. Something that had made sense could suddenly become meaningless; what had momentarily seemed normal could crumble into nothingness. Taussig has described this oscillation as a “doubleness of social being, in which one moves in bursts between somehow accepting the situation as normal, only to be thrown into a panic or shocked into disorientation by an event, a rumour, a sight, something said, or not said—something that even while it requires the normal in order to make its impact, destroys it” (1992:18).

What people meant by “normality” swung back and forth between two points of reference, peacetime and wartime. When Sarajevans spoke of normal life, they meant the prewar way of life and social norms that had been lost amid the violent circumstances of the siege. They saw the way of living that they had been forced to adopt during the siege as abnormal, yet it became strangely normal during wartime. Taussig calls this incomplete shift of mental stance the “normality of the abnormal” (1992:17–18). Sarajevans coined the expression “imitation of life” to mark this coping strategy. They patched together a semblance of existence, living from day to day on terms they could neither finally accept nor directly alter. This stance enabled Sarajevans to conduct themselves according to wartime norms while remembering their prewar norms and enshrining them as the ideal of how life should be. It did not, however, resolve the ethical dilemmas that arose amid their daily struggles: What is an acceptable everyday normality? What is a decent human life? Sarajevans were caught in a constant pendulum swing between the two sets of norms. Should they resist the impulse to run before the sniper? Should they cling to the cosmopolitanism that, like their city, lay in ruins, or should they judge others on the basis of national belonging?

Almost every detail of everyday life was subject to constant evaluation and revaluation. The most intensely charged and deeply disputed domain was that of ethnonational identification. Sarajevans had to reconcile their own lived experiences as members of ethnocultural groups in a multicultural city with the mutually exclusive, even hostile constructions of ethnonational identity that political leaders formulated and the war increasingly forced upon them. Whatever position they chose, it was both existentially unstable and morally charged.

Finding a Method for an Anthropology of War

Most authors who have tried to understand individuals’ lived experience of violence and transform it into words that others can comprehend encounter serious difficulties. The experience of traumatic violence is profoundly personal; it penetrates to the very core of our being. How do we translate existential fear and bodily pain into terms that those who have not shared this psychological and somatic violation of the self can understand? For all who lived through it, the siege of Sarajevo was a “limit situation,”6 plunging them into life circumstances that were on ...