![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Boundaries of Nature

Monsters swam, climbed, walked, and flew in the Atlantic basin in the sixteenth century. Real monsters, or at least they seemed real in the opinion of those who described them, could be found everywhere. Native peoples in the Orinoco basin told the English explorer Sir Walter Ralegh (Raleigh) that if he peered into the woods, he could encounter creatures with faces in the middle of their chests and eventually come upon a city of Amazons.1 European cartographers, after reading the works of cosmographers, squeezed monstra marina into almost every open space on their maps.2 One renowned French surgeon depicted specimens who seemed part human and part animal and provided clinical explanations for how such creatures came to exist.3 Time and again, the monstrous stare out from an early modern page, invading our imaginations and making us wonder why people half a millennium ago thought so often about them.4

Europeans did not need to sail out into the Atlantic to encounter the monstrous. By the time Christopher Columbus set sail in 1492, they already possessed deep knowledge about the monsters that purportedly roamed far away, primarily to the east and the south.5 Texts and images of nonhuman creatures had circulated since Antiquity, dating back at least to the fourth century BCE. Even scripture contained multiple references to marvels and otherworldly entities.6 Details about monstrous creatures circulated in reports by the physician Ktesias from Knidos, who worked in the Persian court, and Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador who took up residence in modern Patna, on the Ganges, after the military expansionary campaigns of Alexander the Great. The geographers and ethnologists of the ancient world collected such reports and republished them, including Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and especially Pliny, who completed his massive natural history in 77 CE. Monsters also appeared prominently in the works of early Christian authors such as the third-century encyclopedist Solinus and the Etymologiae of Isadore, written in the first half of the seventh century. Images of monsters copied from classical texts can be found in eleventh-century manuscripts.7 They proliferated during the medieval period, primarily in the analytical category known as “wonders.”8 Churchgoers could see carvings of them in local shrines along pilgrimages, even at remote outposts such as the Priory of Serrabone, secluded in the hills of the Aspres range not far from the modern border between France and Spain. Dog-headed cynocephali appeared at Vézelay, a major pilgrimage site in Burgundy, and churchgoers across the continent walked by monstrous creatures carved into columns while gargoyles stared down on Parisians from the roofline at Notre Dame.9

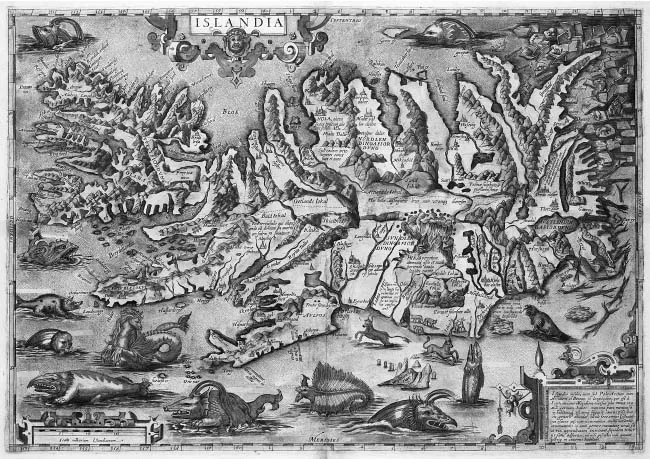

FIGURE 1. Dutch cartographers produced many of the most influential maps of the Atlantic basin in the sixteenth century. Among them was Abraham Ortelius, who created an atlas of the world drawn from various authorities. This map of Iceland in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, first published in Antwerp in 1570, depicted its famed fjords, already long explored by Norse sailors, as well as the fierce denizens that swam off its shores, seemingly patrolling the border of the scarcely peopled island. Wikimedia Commons.

Did Europeans who saw such representations of ludicrous and terrifying beings believe that such creatures existed? Perhaps not. Lucretius, writing in the last century before the Common Era, understood that belief in the monstrous was widespread. But he contended that such entities occurred only in the mind, not in reality. “For certainly no image of a Centaur comes from one living,” he wrote in On the Nature of Things, “since there never was a living thing of this nature,” which explained the absence of a real-world Cerberus, or light-withholding Furies, or a Tartarus “belching horrible fires from this throat,” or a Scylla that was half-fish and half-dog, or a Chimera with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the hind parts of a serpent. None of these things could exist, he was certain, because there was no possible explanation for how they could come into being.10

But knowledge of Lucretius’s ideas almost entirely disappeared for the next millennium and hence could not have halted the spread of visual iconography of the monstrous, which appeared with regularity in bestiaries and church carvings.11 Similar images began to appear with ever-greater frequency in books, too.12 Konrad of Megenberg’s Buch der Natur, written in the mid-fourteenth century, circulated in multiple manuscripts (many still preserved) and appeared in print first in 1475 (and was reprinted five more times before the turn of the next century). The long unpaginated text contained multiple woodcuts of the prosaic aspects of nature, such as insects, flowers, and fish. It also contained representations of the monstrous—including mermaids, a chicken with a crown, a creature that had the head of a man, the body of a large feline, and wings, winged horses, and a creature with the body of a mammal, the tail of a fish, and the head of a tonsured monk.13 By the fourteenth century, scribes had also circulated important manuscripts, such as St. Lambert of Omer’s twelfth-century Liber Floridus, which similarly included the monstrous as well as representations of divine judgments.14 Manuscript news of the monstrous spread across Europe, recycling ideas earlier propagated by Pliny.15

In the town of Fréjus in the south of France, local legend tells that the bishop ordered everyone attending mass to enter the church through its cloister. If this is true, then the parishioners had regular, perhaps weekly, encounters with a provocative series of images painted on wooden panels slotted into the cloister ceilings. The location of the images makes it difficult to see them clearly, since they perch about twelve feet above the floor. Still, after almost seven centuries, the surviving paintings (some have faded almost entirely) still attract the gaze. They evoke a moment when the boundaries between the known world and the unknown constituted a topic of active discussion in the churches, streets, libraries, and courts of Europe—and, indeed, across much of the Atlantic basin.

The cloister at Fréjus offers us a chance to consider the relationship between physical environments and human cultures in the early modern era. Its images reveal a time when there were porous borders between the natural world, which earlier Europeans could understand and examine, and the other, less visible worlds that early modern peoples also believed to exist simultaneously. Those worlds included, as one eighteenth-century scholar (writing about North America) called it, the “païs des ames,” or the country of the souls.16 Nature hosted monsters that roamed forests and seas and occasionally threatened humans. It boasted wonders and prodigies, apparent signs of divine favor or disgust. Nature also offered manifestations of the divine, sometimes in the form of animal spirits that controlled the movements of game or in the guise of an invisible saint who interceded with God on behalf of humans. The clambering chaos of the surviving images at Fréjus—with centaurs, serpents, griffons, and dragons interspersed among mundane images—suggests that the conceptual boundaries of premodern Europeans’ consciousness were mutable, imperfect, and flexible. Similarly, while no one in Europe would have known it, Americans too had created images of what would now be seen as the monstrous, the grotesque, or the supernatural. Fantastic creatures were not just figments of one’s imagination or a familiar literary trope. They were part of the real world, even if they were invisible or existed only in the stories told from an alleged eyewitness to credulous listeners.

FIGURE 2. Depictions of the monstrous could be found in churches across Europe before the sixteenth century. These pictures constitute a small minority of the scores of images that survive from the fourteenth-century commission to decorate the cloister in the cathedral at Fréjus. Photo by the author. (See Plate 1.)

Fréjus sits along the Mediterranean about halfway between Cannes and St. Tropez. Greek traders settled there, followed by Romans, who built the port of Forum Iulii, the market of Julius Caesar. Earlier generations of scholars were consumed with the imperial and late Antique remains of the Roman town. Only a century ago, a historian could write an entire history of the old church there, now the Cathédrale Saint-Léonce, famous for its elegant fifth-century baptistery, without even mentioning the fourteenth-century cloister and the spectacular paintings that cover its ceilings.17 After its port silted, Fréjus became a quiet town and its religious architecture was little known, although in the early seventeenth century Jacques Maretz, a mathematician on the faculty of the university at Aix-en-Provence, included a bird’s-eye depiction of the town in his map of the coast of Provence.18

The painted panels of the cloister ceiling in Fréjus stand in stark contrast to the rest of the stone edifice. These once-brightly painted boards have suffered from the elements over time, but of the 1,235 original panels slotted into the wood ceilings, it is still possible to see clearly about one-third of them. Artists likely painted these works between 1353 and 1368, soon after the Black Death devastated the continent.19 Provence, among the first regions to suffer from the pandemic when it appeared there in 1348, was not alone. Plague swept through much of France, especially from 1360 to 1362.20

Many panels feature iconography common across the continent in the late Middle Ages. About one-third of the surviving images show biblical scenes and saints. Another third presents scenes from daily life of clerics and laypeople in medieval Provence. Three tonsured monks stand side by side in one panel, dressed in seemingly identical flowing white robes. Saint Barthelmy holds the knife that brought his martyrdom in Armenia. Saint John is here too, holding a book, and an angel, poised on the verge of flight, looks on. One painting depicts the celebration of mass. Others feature individual men and women, possibly portraits of the donors whose funds made the project possible. Angels can still be seen, their wings crammed to fit into the borders of panels.21

Yet many images in Fréjus have no obvious religious theme. One features an acrobat, groups of dancers appear in several panels, and men hunt, fish, and go falconing in still others. Some pictures depict men at war. In one, two women sit at their toilet preparing themselves to be seen, while a companion holds vials of medicine or cosmetics. One woman, gingerly holding her dress, is gathering plants while another grips her formidable hairdo. One talented man takes a ride on the back of a pig. Painters depicted local animals and birds too, including a hound about to pounce on a boar. The artists seem to have been familiar with books depicting wildlife from well beyond Europe’s borders, in Asia and Africa. A whole catalog of exotic beasts roamed above the heads of late medieval congregants.22

Mingling among these quotidian scenes are depictions of monsters and prodigies. It is one thing for a symbolic lamb to strut around carrying a cross, a well-known visual representation of Christ. But many of the nonhumans do not fit such religious iconography. A painting of a unicorn might not seem too shocking on its own. But what to make of the head of a bald man perched on a neck so long that it doubles back in the painting to peer over the creature’s nonhuman body? There are centaurs here too, of both sexes, and dragons with jagged teeth. Hybrids abound, with humorous and hideous appendages, while others seem to be crosses of real with mythical beasts. One has a human head on its chest—a blemmye—and, as if that was not terrifying enough, it wields a spear. There are people with the heads of dogs, a...