eBook - ePub

The Swahili

Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500

This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Swahili

Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"As an introduction to how the history of an African society can be reconstructed from largely nonliterate sources, and to the Swahili in particular, ... a model work."— International Journal of African Historical Studies

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Swahili by Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1SWAHILI AND THEIR HISTORY

Dotted along the eastern coast of Africa from Somalia to Mozambique are a number of old Swahili towns (see map 1). Perched on the foreshore or on small offshore islands, their whitewashed houses of coral rag masonry crowd around a harbor where a few seagoing dhows are tied. Among the coral houses are a number of small mosques where men from the immediate neighborhood gather in their white gowns and small embroidered caps for prayers and outside of which they gather afterward to discuss town affairs in measured tones. Their wives and older daughters are not to be seen until evening, when, under cover of darkness and their loose, flowing black robes, they visit discreetly with their female relatives and friends.

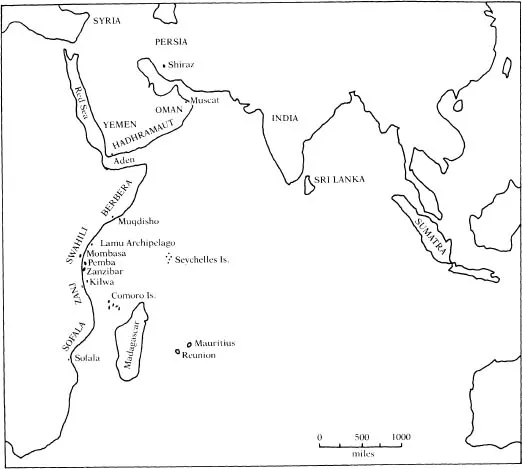

The East African coast has long been involved in the wider world of Indian Ocean trade and culture. From early in the first millennium after Christ, dhows have sailed south from the Arabian peninsula and the Persian Gulf on the annual northeast monsoon to trade pottery, cloth, and iron tools for African slaves, ivory, gold, timber, shells, dyes, and perfumes, returning home after the monsoon winds shifted around to the southeast. Although African goods reached the Greco-Roman world before the third century and China by the seventh, trade during the first millennium was largely with Arab and Persian traders from Shirazi ports in the Persian Gulf. For much of the second millennium, however, East African trade passed to the Arabian peninsula. The first sign of the shift occurred in the ninth century with the rise of the First Imamate at Oman, but the focus of trade shifted permanently during the twelfth century to southwestern Arabia (Aden, Yemen, and the Hadhramaut) and, later, to Oman.

Map 1. Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean

Most trade in East Africa itself during the first millennium was coasting trade, conducted on the beach between seafaring Arab merchants and African residents of the mainland. Only two market towns (Rhapta and Kanbalu) are known to have existed before 800, but we still do not know where they were located. The first permanent trading settlements that we can identify were established during the ninth century in the Lamu Archipelago (at Pate, Shanga, and Manda) and on the southern Tanzanian coast at Mafia and Kilwa. By the eleventh century, trade centered on Muqdisho in Somalia, where local dhows brought gold north from Mozambique and ivory, slaves, and other goods from elsewhere along the coast to trade with Arabs during the annual trading season. Muqdisho was noted in the thirteenth century for its wealth, size, and Muslim character, and Arabs had already begun to settle in the town. During the fourteenth century, however, Muqdisho lost its monopoly over the gold trade to Kilwa, located nearer to the gold fields at the southern limits of the monsoon trade. Kilwa continued to dominate coastal trade until conquered by the Portuguese in 1505, when the center of trade shifted north again to Mombasa in the fifteenth century and Pate-Lamu in the sixteenth. Trade and the coastal towns were badly disrupted during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by ongoing Portuguese raids and conquests until Oman defeated the Portuguese late in the seventeenth century, initiating two centuries of Omani Indian Ocean dominance, which culminated in the establishment of the Omani sultanate at Zanzibar and the extension of Omani power and cultural influence to towns all along the coast during the nineteenth century.

Though the Muslim maritime towns of the coast were not exceptional by themselves, they contrast with the rest of eastern and southern Africa. The Swahili language is spoken in towns scattered along two thousand kilometers of coastline, while their neighbors on the mainland speak dozens of different local languages. In the drier areas of Kenya and Somalia to the north, these neighbors are pastoralists, herding cattle, camels, sheep, and goats, whereas in the more fertile areas of southern Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique they raise maize, eleusine, millet, and sorghum together with various fruits and vegetables and small numbers of livestock. The peoples of the mainland rarely live in concentrated villages and never in coral houses, preferring to construct their thatched mud and wattle houses among the fields they farm or to erect simple temporary shelters as they migrate with their herds. And until recently very few were Muslim; most respected the spirits of their own particular lineage and clan ancestors.

Coastal Swahili-speakers have long stressed the differences between themselves and their neighbors, emphasizing their descent from immigrants from Shiraz in Persia and from Arabia who had come centuries earlier to the African coast to trade and who stayed to settle, build coral towns, live a sophisticated urban life, and rule. Later, when Omanis established themselves in Zanzibar and sought to impose their rule over the coast, Arabs exerted strong economic and cultural influences. Trade boomed, and during the prosperity that followed merchants from the Hadhramaut in southern Arabia became prominent community leaders, immigrant sharifs reformed and revitalized coastal Islam along contemporary Arabian lines, and people built elegant houses copying current Arabian and Indian features.

Thus, when Europeans visited the coast in the nineteenth century, Swahili towns appeared to be products of a Persian and Arabian diaspora that had spread around the Indian Ocean. The towns were not then very numerous or very large, numbering no more than a dozen containing a few thousand inhabitants each, but abundant evidence was found in ruins all along the coast of a vibrant period of Swahili civilization in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, marked by extensive and elaborate building and large-scale imports of Islamic and Chinese pottery, that lasted until the Portuguese destroyed a number of towns during the sixteenth century in their attempt to monopolize Indian Ocean trade. With the loss of trade, the coast went into decline until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the Omanis initiated a new period of prosperity and of Arab influence.

The marked Arab appearance of the coastal towns, in contrast with the villages of neighboring Africans, and the claim to Arab and Persian origin made by the Swahili themselves have long led historians to portray coastal culture as an alien Muslim civilization divorced from the cultures of indigenous Africans, “strange foreign jewels on a mournful silent shore.” Writing in the 1890s, Justus Strandes observed of Mombasa:

Shirazi Sheikhs are described as the earliest rulers, and according to the History of Kilwa found by the Portuguese, Muhammad the son of Ali bin Hasan, the founder of Kilwa, is considered to be the first of the line. These written accounts are confirmed by the verbal traditions of the native inhabitants. Many buildings now lying in ruins are characteristic of Shirazi building. Even today the inhabitants of whole villages like to boast of Shirazi descent. The fact that it is generally the chiefs, or the village notables, members of the ruling families of the past, who usually describe themselves as being descendants of the old Persian emigrants, confirms the credibility of the claim. As is natural, the centuries which have passed, and the continued intermarriage with the native African have done much to efface the characteristics of the original stock. They are not, however, pure Bantu and it is indeed remarkable how frequently the Aryan physiognomy and bearing distinguishes these people from the Africans amongst whom they live.1

Though archaeologists digging in the ruins of coastal towns found little specific evidence of Persian influence, they continued to emphasize the foreign nature of coastal civilization, attributing basic architectural styles and subsequent innovations to Arab inspiration.

The religion was Islam and the fundamental bases of the culture came from abroad. In language and the materials of everyday life local African influence was stronger. The standing architecture however reflects little African influence and its forms are entirely alien to those of the hinterland—its origins were outside East Africa and it is present fully fledged in the earliest known buildings. If anything, only a slow subsequent decline can be traced in both design and technique. Nevertheless, the resulting style is individual to the coast and homogeneous throughout its length. The culture was provincial—initiative was always from abroad.2

Similarly, linguists stressed the large number of Arabic words in Swahili and the use of Arabic script in writing Swahili, while ethnographers wrote of the Muslim basis of Swahili society. The overall message was consistent: “These cities of the coast look out over the ocean; their society was primarily Islamic, and their way of life mercantile. . . . We should picture this civilization as a remote outpost of Islam, looking for its spiritual inspiration to the homeland of its religion.”3

Recently, a number of discoveries and revised perspectives have begun to reveal the deep indigenous bases of Swahili culture and history. Archaeologists have begun to analyze more closely the evidence for the early period of Swahili history between ca. 800 and ca. 1100 before they began trading extensively, building in coral rag, and converting to Islam. Linguists have shown that Swahili is clearly an African language, closely related to the Bantu languages now spoken along the northern Kenya and Somali coast, and that it has acquired much of its extensive Arabic vocabulary only in the last few centuries. Anthropologists have started to expand their studies from the cultures of the towns to those of Swahili fishing villages and mainland neighbors to uncover basic features of Swahili culture that reflect wider regional patterns. And historians are now reassessing documentary accounts and Swahili oral traditions in the light of these discoveries to reconstruct the local history of the Swahili that underlies the Arab veneer. These discoveries have fundamentally revised our view of Swahili history, so it is important to examine them and the implications they have for that history carefully.

The Swahili Language

Much of the traditional view of the origins and status of Swahili is captured by the following extract from a Nairobi newspaper:

History has it very clearly that Swahili is a combination of more languages than one, the major one being none other than Arabic. When the Arabs came to the East Coast of Africa before the exploitation era and consequently colonized it, they had no way of communicating with the indigenous people they met. Gradually and inevitably they tactically (and rightly so) combined what of their language they could with the languages that were being spoken there. There were many and still are—Giriama, Banjuni [sic], Digo, etc., not to mention those spoken further north and south of the East Coast of Africa. The result—Swahili. Some of the most prominent words in the language owe their origin to Arabic: salamu, salama, chai, lakin, etc.4

The first, and most obvious, fallacy here is that the most important feature of Swahili is its Arabic component. This feeling is widespread in both popular and academic writing and takes many forms. It is akin to saying that English, a Germanic language, is really a Romance language because of French influence during the centuries following the Norman invasion. This feeling is distorted because it fails to distinguish between what is inherited in a language and what is absorbed later. Swahili is clearly an African language in its basic sound system and grammar and is closely related to Bantu languages of Kenya, northeast Tanzania, and the Comoro Islands, with which it shared a common development long prior to the widespread adoption of Arabic vocabulary. Though some Arabic words were assimilated into Swahili before A.D. 1500, most are attributable to the post-Portuguese period. The Arabic material is a recent graft onto an old Bantu tree.

The second fallacy is that a single language arises in different places and, presumably, at different times: the Arabs “tactically . . . combined what of their language they could with the languages that were being spoken there.” This view sees Arabic as a catalyst, which, on coming in contact with any available coastal language, ineluctably turned it into a form of Swahili. Another variant of this fallacy, while denying that Arabic was the catalyst, nevertheless sees Swahili as arising simultaneously at several different points along the coast. This polygenetic view of Swahili contradicts what we know from countless other languages in the world. A language arises in one place, over a period of time. Its speakers multiply, and the language starts to diversify internally. Its community splits up and some of its speakers move away, thus increasing the linguistic differentiation. It was during this stage in the history of Swahili that Arabic intervened. A language is created in a specific area and time, which is not to be confused with its subsequent development and differentiation.

The final objection to the view expressed in the quotation is the confusion of people and language. Most outsiders coming to the coast are usually struck by the images evoked in the opening paragraphs of this chapter, with their suggestion of foreign dress, religion, buildings, way of life, and even physical appearance of the people. From there it is an easy step to assume that the language of these people is also swamped with foreign elements. Though we do not deny that language and culture are intertwined or that foreign elements have been absorbed into the Swahili language, it behooves us to avoid any simplistic association of linguistic and nonlinguistic habits and to look more carefully at what in the language is Bantu and what is not, and how and when this non-Bantu element appeared.

Much of the distortion of the nature of Swahili is due to the lack of serious debate about the historical background of Swahili. Though there has always been considerable interest in the Swahili language, this largely concentrated on Swahili literature and, more recently, on the development of the language as a lingua franca for Tanzania and Kenya. Little interest was shown in its historical development, and that focused largely on the allegedly Swahili words quoted by early Arab travelers and on the language used in the earliest Swahili literature. But since the words cited by the Arabs are few in number, unreliable in form, and often present in neighboring languages, it is difficult to determine if most were in fact Swahili. Similarly, the evidence for the language of older Swahili literature is negligible. Most Swahili manuscripts date from the last two centuries, a very few possibly from the seventeenth century. Swahili literature was essentially oral, and manuscripts were handed from scribe to scribe, each of whom felt justified in revising vocabulary, content, grammar, and dialect features in accord with current practice. Little was fixed. In addition, there arose a stylized convention for the language of verse, which in the last few centuries was based on the dialect of Lamu. The result is that very few manuscripts have reached us in a form of Swahili ascribable to a period earlier than the eighteenth, or, possibly, the seventeenth century. When we consider that the first signs of Swahili appeared in the ninth century, it is obvious that the language of the manuscripts has limited historical value.

Languages develop when people speaking a common language become separated from one another. In time the speech of each community changes, evolving into different dialects and eventually different languages. The problem linguists face in studying this development, however, is that they must st...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Swahili and Their History

- 2. The African Background of Swahili

- 3. The Emergence of the Swahili-Speaking Peoples

- 4. Early Swahili Society, 800–1100

- 5. Rise of the Swahili Town-States, 1100–1500

- Appendixes

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index