![]()

Chapter 1

Mass Murder in Eastern Congo, 1996–1997

Filip Reyntjens and René Lemarchand

A story as macabre as any other, involving genocidal attacks against refugees some of whom were guilty of genocide themselves; mercenaries of the traditional “dogs of war” variety; the smashing of refugee encampments and the perversion of humanitarian assistance; Western businessmen with mobile telephones and an intense desire to follow the victors and fix new contracts for exploiting Zaïre’s diamond and copper mines; and the defeat of a dying old dictator. All of these and more were involved in a vicious game of pursuit through the steaming jungles of eastern Zaïre.

—William Shawcross, Deliver Us from Evil

Of the countless human rights violations committed by President Paul Kagame’s army before, during, and after the Rwanda genocide, the systematic extermination of tens of thousands of Hutu civilians in eastern Congo (then known as Zaïre) between October 1996 and September 1997 can only be described as a case of mass murder. Some would not hesitate to call it a genocide—a term used by a UN panel to describe what it perceived as a distinct possibility.1 Very few outside Central Africa remember the horrendous scale of this human tragedy, let alone the complicated circumstances behind it. Nonetheless, the disastrous sequel of these events continues to plague the relations between Kigali and Kinshasa, and to mortgage the prospects for a durable peace in eastern Congo.

Although the exact number of victims will never be known, several things are reasonably well established. One is that, contrary to official Rwandan propaganda, the victims included a majority of civilians rather than being made up exclusively of génocidaires. Another is that the number of refugees who chose to return to their homeland—or had no other option—after the destruction of their camps must not have exceeded half a million.2 This means that of the 1.1 million refugees who fled to the Congo in the wake of the genocide, more than half remained unaccounted for. Tens of thousands died of hunger, disease, and sheer exhaustion as they fled the avenging arm of the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA); others, mostly former interahamwe (civilians) and ex-Forces Armées Rwandaises (FAR), managed to survive the manhunt, thanks to their weapons and physical stamina; the remainder, consisting mainly of women, children, and the elderly, fell under the blows of the RPF.

Estimates of the number of refugees killed by RPF soldiers vary widely. In an interview with the news agency Congopolis on October 15, 1997, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Herman Cohen came up with what seems a wildly exaggerated figure: “I believe that the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA, ex-RPF) massacred as many as 350,000 Hutu refugees in eastern Congo.” Stephen Smith’s “guesstimate” of “200,000 Hutu killed by Rwandan troops during Laurent Kabila’s march to power” could be closer to the mark.3 On the basis of a careful scrutiny of the evidence another observer, K. Emizet, arrives at a death toll of about 233,000.4

That such massive bloodshed should have made so little impact on Western consciousness is due in no small part to the deliberate efforts of the Kagame government to conceal the truth by a sustained campaign of disinformation—a task in which it received considerable assistance from the U.S. Embassy in Kigali. What Lionel Rosenblatt, president of Refugees International (RI), refers to as “a reverse form of the CNN factor” suggests another explanation: “Because the current humanitarian catastrophe in eastern Zaïre is not on television, many don’t believe it’s happening (or feel that, politically, they can afford to ignore it).”5 Not unnaturally, public attention was largely focused on the more widely publicized dimension of the war in eastern Congo. The triumphant march of the Rwanda-backed rebels to Kinshasa all but eclipsed public attention to the horrendous crimes that have accompanied its victory. Philip Gourevitch aptly described the image that impressed itself most forcefully on the minds of casual observers: “The Congolese rebellion,” he averred, “offered Africa the opportunity to rid itself of its greatest homegrown political evil, and to supplant the West as the arbiter of its own political destiny.”6 As we now realize, Kagame’s Rwanda—the central orchestrator of Kabila’s victory—emerged as the real arbiter of the Congo’s destiny, but at horrendous cost to the Congolese and to many of its own citizens.

The Roots of Disaster: Security Threats and Minorities at Risk

Before going any further something must be said of the potentially explosive regional situation that came into existence in the wake of the Rwanda genocide. In the context of an increasingly tense relationship among the three principal actors—Mobutu’s Congo (then known as Zaïre), ethnic Tutsi communities of eastern Congo, and the new rulers of Rwanda—the provocations of Hutu (and Congolese) extremists can best be seen as the fuse that ignited the wider conflict.

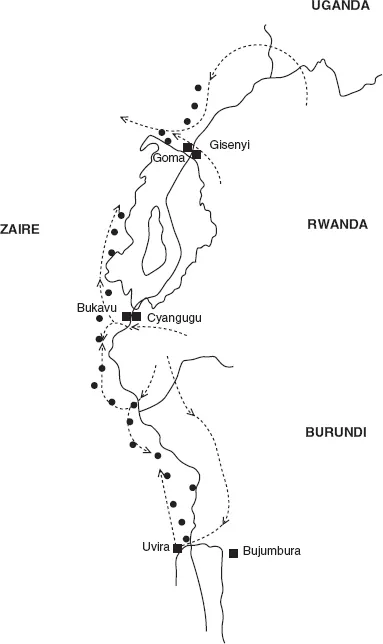

At the root of the crisis lay the existential threat posed to Rwanda’s security by the presence of thousands of Hutu hard-liners in the refugee camps. Of some forty camps strung along the border with Rwanda and Burundi, the two largest, Katale and Mugunga, both in North Kivu and sheltering 202,566 and 156,115, respectively, accounted for nearly one-third of the total refugee population of 1.1 million registered by the UNHCR in June 1996.7 The camps’ strategic locations, the control exercised by armed extremists over the civilian refugee population, the refugees’ widespread support of the radical opposition movement in exile, the Rassemblement pour le retour des réfugies et la démocratie au Rwanda (RDR), the substantial military assistance Hutu hardliners received from Mobutu, and the cross-border raids organized from the campsites—all this made the Rwandan authorities acutely conscious of the clear and present danger looming on their doorstep.8

Insecurity inside the camps only served to magnify the external threats posed to Rwanda. In most cases, recourse to violence was the work of Hutu extremists trying to assert their control over civilians. In response to mounting criticisms of the international community for its inability to rein in the extremists, Sadako Ogata, the head of UNHCR, decided to turn to Mobutu’s troops to maintain security in the camps, a step that turned out to be totally counterproductive. What became known as the Contingent Zairois Chargé de la Sécurité des Camps (CZSC)—consisting of some 1,500 subcontracted Zairian soldiers—proved even more dangerous than the troublemakers they were sent to control, as many reportedly went about stealing refugee property, raping women, and even selling weapons to those they were supposed to disarm. Most of them ran away when confronted with units of the Rwandan army.

A matter of equal concern for Kigali was the menacing tone of the provincial authorities in North and South Kivu toward the ethnic Tutsi minorities indigenous to each province. Although most of them consider the Congo their homeland and trace their ancestry to long-established immigrant communities, the so-called Banyamulenge of South Kivu (“the people of Mulenge”) and the ethnic Tutsi of North Kivu claim strong cultural and psychological affinities to the Tutsi of Rwanda. That many volunteered to join the ranks of the RPF in the early 1990s as it fought its way into Rwanda testifies to their sense of solidarity with their kinsmen in exile. As Congolese politicians intensified their anti-Tutsi rhetoric through much of 1995 and 1996, threatening to expel all Tutsi and Banyamulenge residents—now globally seen as foreigners collaborating with their Rwandan kinsmen—Rwanda’s sympathy for “the near abroad” only strengthened its sense of revulsion toward the Mobutist state and its provincial satraps.

Eastern Congo has a long history of anti-Rwandan sentiment going back to the years immediately following independence when Kinyarwanda-speaking elements were viewed with mounting hostility by local Congolese politicians. There was no precedent, however, for the intense anti-Tutsi hostility triggered by the outpouring of Hutu refugees from Rwanda to North and South Kivu. Until then, Hutu and Tutsi were objects of equal distrust by self-styled “native Congolese,” being lumped together as they were into a single “Banyarwanda” (or “Rwandophone”) entity. Now the Tutsi were singled out as the prime cause of the problems facing the Congo. Hatred of the Tutsi found expression in countless acts of aggression and a ratcheting up of threats, culminating with officially supported anti-Tutsi public demonstrations in Bukavu and Uvira. A number of Tutsi were killed in Bukavu during a “march of anger” on September 18, 1996; a week earlier, according to Amnesty International (AI), dozens of Tutsi were arrested in Uvira. Illustrative of the venomous mood among “native” Congolese is the statement of a local civil society organization in South Kivu comparing the Banyamulenge to “disloyal snakes who have abused Zaïrian hospitality and must be sent back to Rwanda, where they come from.”9 Ethnic tension reached its peak after the South Kivu governor called for “all Bayamulenge to leave Zaïre within a week,” adding that “those remaining would be considered as rebels and would be treated as such.”10

In what turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy many of the Banyamulenge subsequently joined Kabila’s rebel organization, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo/Zaïre (AFDL), a broad-based coalition of anti-Mobutist forces stitched together through the joint efforts of Kagame and Museveni. Long before its existence became known ethnic Tutsi were being actively recruited by President Kagame to beef up his armed forces. As early as 1995, according to President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, some 2,000 joined the RPA in anticipation of a major strike against the refugee camps, later to be joined by an additional 2,000. By June 1996, many Banyamulenge “rebels” were being trained in northwestern Burundi, under the protection of the predominantly Tutsi Burundi army. Among the truckloads of soldiers that crossed the Burundi border into eastern Congo in September 1996 many were Banyamulenge, eager to serve the RPA units as their scouts and auxiliaries in their march to the campsites.11

Securing Eastern Congo

What began as concerted attacks against urban communities—Uvira fell on October 24, Bukavu on October 30, and Goma on November 1—quickly mutated into a systematic “clean-up” of the refugee camps and immediately thereafter into a wide-ranging manhunt directed against all refugees, be they civilians, interahamwe, or ex-FAR. The largest of the camps, Mugunga, now home to 200,000 refugees, was attacked on November 14, two weeks after the fall of Goma. During those two weeks frantic efforts were made by the UNHCR, with the active support of France and Canada—and against the strenuous opposition of the United States and the United Kingdom—to open up safe corridors that would “simultaneously allow delivery of relief in one direction, and the secure passage of refugees back to Rwanda in the other.”12 No less important was the assembling of a multinational force of some 10,000 to 12,000 troops to ensure the safety of the operation, a task entrusted to Maurice Barril, senior military adviser to UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali (of which more later). Meanwhile, in clear disagreement with the Franco-Canadian initiative, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees, and Migration Phyllis Oakley flatly suggested cutting off all assistance to the refugees in order to force them back into Rwanda, a country where, in her words, “we have seen a great improvement.”13

As has become painfully clear, the destruction of Mugunga on November 14 was a move carefully calculated by Kagame, and presumably with the full approval of the United States,14 to ensure the failure of the UNHCR’s humanitarian strategy and at the same time present France and Canada with a fait accompli. In Samantha Power’s blunt assessment, “They decided to strike a knockout blow before the international troops had time to assemble.”15

After a sustained shelling of the campsites, units of the AFDL and RPA moved in from the west, leaving the refugees no other option but to walk back to Rwanda. As noted earlier, as many as one-half million poured back into Rwanda. Pointing to the massive return of refugees, Kagame made the argument that those who stayed behind could safely be presumed to be génocidaires—their refusal to come home being cited as proof of their culpability. In such circumstances, there was no need for either the safe corridors or the MNF. What Kagame failed to recognize is that, in addition to thousands of interahamwe and ex-FAR, hundreds of thousands of civilians were now on the run, desperately trying to evade the tightening noose of the search-and-destroy operations conducted by the RPA, who quickly caught up with the huge flow of refugees from other camps, also desperate to outpace their pursuers.

Figure 1.1. Attacks on Refugee Camps (Fall 1996)

The Rwandan army played the key role in the destruction of the camps, as it would in the next few weeks in the wanton slaughter of innocent civilians. Long before the attack on Mugunga, the Voice of America made clear the implication of the RPA: on October 28, Rwandan authorities, speaking on condition of anonymity, admitted that “the Rwandan government was sympathetic to the Banyamulenge and that some officers from the Rwandan army had helped organize rebel groups.” The participation of Rwandan troops was particularly clear in the capture of Goma after attack units were sent in from Rwanda by land and across Lake Kivu. By early November the borders between the Congo and neighboring Rwanda and Burundi had been secured by a buffer zone stretching along 250 kilometers from Goma in the north to Uvira in the south.

The next phase was now about to begin. In addition to the countless men, women, and children who died of hunger, disease, and sheer exhaustion in a murderous game of hide-and-seek, tens of thousands were savagely murdered.

The Manhunt

As the exodus of refugees wound its way toward Kisangani and ultimately to Mbandaka, the last station on their Golgotha, new camps were hastily assembled in hopes that their inhabitants would be spared. For survivors of the ordeal, the names Shanji, Lula, Ubundu, Kasese, and Tingi-Tingi are not just geographical references to temporary campsites; they are evocative of collective agonies that have been virtually obliterated from the rest of the world’s memory.

This is how Howard French, one of the rare journalists to visit the camps, described what he saw at Tingi-Tingi as his old DC-3 landed nearby:

I looked out the window as we banked for the descent and discovere...