![]()

Chapter 1

The Majority-Minority Relationship and the Formation of Informally Institutionalized Conflict Dynamics

After defeating communism as an ideology, the liberal creed in the early 1990s appeared to triumph globally. Capturing the Zeitgeist of the time, institutionalist accounts offered democratic solutions for mitigating ethnic conflicts by such strategies as respect for minority rights in line with international norms, power-sharing agreements, fair electoral rules and proportional representation, ethnic balance in military and police structures, decentralization, autonomy, and federalization.1 Principles of respect for diversity, division of power, and competition for power were placed at the core of these solutions.2

By the late 1990s some scholars became aware that such institutional solutions might be productive for a more mature polity, but not for a transitional setting. Policies leading to the devolution of power to minority regions—such as decentralization, autonomy, and federalization—were problematized because of their controversial consequences. Sometimes they relieved minority discontent by facilitating representation, but at other times they aided secessionist struggles associated with more violence.3 The devolution of power to highly concentrated minorities whose loyalties lay outside the state became especially questionable.4 Aware of such challenges, in the 2000s scholarly voices sang in harmony that transitional regimes were among the most violence prone, especially in polities with highly divided societies.5

Transitions can significantly weaken state institutions, which in turn may provide fertile ground for nationalist activities by dominant or subordinate peoples. In Eastern Europe, the transition from communism exerted simultaneous pressures to replace one-party dictatorship with multiparty democracy and a command economy with a market economy, and often to build the state anew, which weakened state institutions.6 When institutions are weak, using nationalism for instrumentalist purposes faces few constraints. Elites may mobilize the population by evoking ethnicity as “the only politically relevant identity.”7 Public discussion may become skewed by state or monopolistic control of the media, and average citizens may back groups or parties based on incomplete information.8 Governance suffers: state ability to provide political goods diminishes and corruption rises.9 Under such conditions, groups that can provide services gain popularity, often invoking a nationalist doctrine while building patron-client relationships.

This chapter focuses on the early transition period (1987/89–1992), when structures and institutions established during communism were fundamentally transformed. Under conditions of high volatility and uncertainty, the choices of majority and minority elites mattered to how the new “rules of the game” of interethnic relations would be defined, and how the ground would be laid for the establishment of conflictual, semiconflictual, and cooperative dynamics.

In this chapter I explore three interrelated questions:

• How did antecedent conditions in Bulgaria, Macedonia, and Serbia influence the options available to majorities and minorities in decision-making during the critical juncture at the end of communism?

• Did the opening of the political system for political competition in each case precede or follow changes in minority status and how did it affect majority-minority relations?

• How did the changes in constitutional status of the Turks of Bulgaria, the Albanians of Macedonia, and the Albanians of Kosovo (Kosovars) create new rules of the game in a transitional environment?

I argue that three factors were highly important for establishing the rules for ethnonational actions during the critical juncture and subsequent development of cooperative (Bulgaria), semiconflictual (Macedonia), and conflictual (Kosovo) dynamics. First, in the volatile late 1980s, communist elites within the dominant ethnic group competed with rival ideas on minority status. When a faction won, it sealed its vision about the minority’s status in the newly adopted constitution. I show the importance of the relative change in minority rights compared to the communist period, rather than the absolute scope of minority rights judged against global or regional normative standards. The relative scope of decreases in status also mattered. Constitutional changes created a political threshold that propelled causal chains of majority-minority interactions leading to different degrees of violence over time.

The second factor was a decision-making sequence that aimed at reinforcing the earlier majority decision. Majority elites decided to make minorities comply with these decisions through co-optation or coercion. The third factor, depending on the combinations of majority choices about the type of minority status change (increase/decrease) and strategy for compliance (co-optation/coercion), was the development by the minorities of a reactive sequence of counter-strategies. These took the form of rejection of the state, using state institutions to advance their goals, or both. In Bulgaria, policy liberalization in the form of slightly increased minority constitutional status and co-optation worked to reduce ethnic Turks’ demands and minimize subsequent levels of violence. In Macedonia, policy restriction in the form of moderately decreased status combined with co-optation prompted a two-pronged strategy among the Albanians. The level of violence remained low when they pursued their goals through formal state channels, but increased when they engaged in informal clandestine activities. In Kosovo, drastically decreased status, in combination with coercion, triggered the establishment of clandestine minority institutions that clashed regularly with government forces.

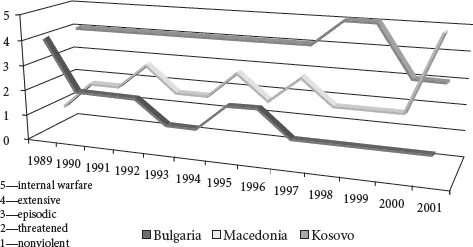

Historical, cultural, and economic explanations relevant to the end of communism are also important, and others are woven in later in the chapter, at different stages of process-tracing. Interactions between majorities and minorities during communism created some of the antecedent conditions informing agents’ choices during the formative period. Majority-minority relations during the critical juncture have theoretical implications. Competition among communist elites within the dominant ethnic group, timing of minority status change in relation to opening for political liberalization, and the nature of constitutional changes played important roles. Specific reinforcing and reactive sequences helped establish conflictual, semiconflictual, or cooperative dynamics that became ultimately responsible for degrees of ethnonational violence over time. Figure 2 presents this evolution through the 1990s.

Timeline

| Bulgaria |

| 1989 | Government violence, expulsion, and expropriation of minority property. |

| 1990–1992 | Nationalist demonstrations against the minority, minority boycotts of schools. |

| 1993–1994 | Nonviolent channeling of interests. |

| 1995–1996 | Threats by the government and the minority. |

| 1997–2001 | Nonviolent channeling of interests in most policy areas. |

| Macedonia |

| 1989 | Primarily nonviolent channeling of interests. |

| 1990–1991 | Minority demonstrations, boycotts. |

| 1992 | Violent clash between minority and government forces. |

| 1993 | Tensions around the discovery of a paramililtary conspiracy. |

| 1993–1994 | Minority and governmental threats, constitutional boycott by the minority. |

| 1994 | Tensions around elections and in the parliament. |

| 1995 | Minority demonstrations crushed by the police. |

| 1996 | Tensions around the functioning of a semi-parallel university. |

| 1997 | Minority demonstrations crushed and leaders imprisoned. |

| 1998 | Tensions around the semi-parallel university. |

| 1999–2000 | Tensions related to the Kosovo crisis. |

| 2001 | Guerrilla clashes with government forces. |

| Kosovo |

| 1989 | Several violent demonstrations crushed by the police. |

| 1990–1997 | Government violence against minority members on a daily basis. |

| 1998–1999 | All out clashes between guerrillas and governmental forces involving civilians on a large-scale basis. |

Figure 2. Evolution of ethnonational violence, 1989–2001.

Alternative Explanations: Historical, Cultural, and Economic Factors

Accounts claiming that ancient hatreds and historical enmities explain violence in the Balkans only perpetuate nineteenth-century ethnic stereotypes and have been rightfully refuted by sound scholarship.10 My account adds more fuel to this fire: Serbs and Albanians, Macedonians and Albanians, and Bulgarians and Turks harbor many historical enmities, but they did not have the same levels of violence during the transition period. This holds true even if we consider “sleeping beauty” theories: that ancient hatreds dormant during the highly repressive communist regime were awakened with the end of communism.11

Aware of this easy dismissal of hatred-based accounts, a few related theorists took a step farther. Petersen argued that “hatreds” do not need to be ancient to lead to violence. Emotions such as fear, hatred, resentment, and rage are part of the human condition. When triggered by landmark external events and structural change, they provide the mechanisms driving groups to violent ethnic mobilization.12 Kalyvas found that personal vengeance is a recurrent motive for participation in civil wars.13 Kaufman argued that elites cannot mobilize ethnic groups for violence unless deeply ingrained, socially acceptable “myth-symbolic complexes” justify hostility against the other group.14 These accounts go into the mechanisms leading to ethnonational violence, but they do not explain the situations I am examining. I do not reject the importance of emotion following constitutional changes, or of deeply ingrained myths, but I stress that specific sequences of majority-minority relations laid the foundations for conflict dynamics.

Language is considered a primary culprit for the emergence of contentious politics in the Eastern European context, where nationalism developed along linguistic lines. “Linguistic territoriality” designates the expectation that “the national space would be mapped by a national language” officially standardized.15 Language conflicts have their own dynamic compared with other forms of cultural conflict, civilizational or religious.16 Classic works on ethnic conflict observe that language differences can easily leave politics and become a threat to peace. More recent large-N studies demonstrate exactly the opposite: greater linguistic differences do not lead to higher levels of violence, but tend to relocate the conflict from the military to the political realm.17 Language conflict offers only a partial explanation in my cases. Certainly, linguistic tensions exist between minorities that do not speak Slavic languages (Albanians, Turks) and Slavic-speaking majorities (Serbs, Macedonians, Bulgarians). But these differences did not become politically salient unless they were attached to autonomist or territorial demands. Evidence (see below) supports David Laitin’s argument that language grievances are not associated with group violence per se, but can turn dangerous in conjunction with other discriminatory factors such as kin-state support of minority grievances or a rural basis for contention.18

Civilizational and religious differences are not explanatory either. I side with the critics of the much debated “clash of civilizations” thesis of Samuel Huntington, who argued that after the end of the Cold War the world’s conflict lines would be drawn along cleavages of civilization and religion, most notably Christianity and Islam.19 Although the three minorities of this research are Muslim and the majorities Christian Orthodox, the outcomes in levels of violence vary. Also, while religion was certainly politicized, it did not play a strong nation-building role and was subsumed under other nationalist claims. For example, Albanians have often emphasized that the “religion of Albanians is their Albanianism,”20 not that Albanians are Muslims.

Economic arguments are also inconclusive. Some scholars find that the determinants for insurgency are primarily based on economic greed, because rebels calculate more expected gains from war than from productive economic activity.21 Some argue that political grievances and opportunities for violence rather than greed and economic motivations pose better explanations.22 According to others, economically strong regions do initiate secessionism.23 Most scholars assert that higher levels of violence are more likely in economically weak states that are also institutionally weak and have difficulty controlling rebellious activity within their borders. There is an association between high poverty and onset of civil war, since poverty reduces the opportunity costs of forgoing productive economic activity for participating in armed rebellion.24

Empirical evidence suggests that economic decline and rise in unemployment toward the end of communism are important factors, but they did not always lead to large-scale violence. Kosovo was the poorest region of former Yugoslavia, Macedonia was not far ahead, and both were less affluent than Slovenia, Croatia, or Serbia. In 1988, “the per-capita output in Kosovo was 28 percent of average output in ...