![]()

PART I

Discovery

This book begins with a simple premise, that it is possible to write a history of Native North America in the seventeenth century. Of course, any history of Native peoples during this time period must also be a history of the encounter between the indigenous peoples of this continent and the European empires that brought settler colonialism to the Western Hemisphere. And so one might expect that this Native history of North America is also a book about the discovery of the New World.

The idea that Europe “discovered” the Americas is obviously flawed as a historical concept. The two continents existed before Europeans arrived and began to interact with the peoples they found living there. From a European perspective, however, the Americas were a New World because they had been conspicuously absent from the Old World that they had known for millennia. This place and its people were not in the sacred texts and origin stories of Europe, Asia, or Africa. They were absent from maps, and even from the historical imagination. Given this absence, it makes sense that colonists thought of this place as a New World even though it was occupied by people who had a long history in the Western Hemisphere.1 It also makes sense that they relied on a language of discovery to describe their experiences in a place so completely unknown to them.

These are the biases that encode virtually all of the textual evidence that historians must rely on to write the history of seventeenth-century North America. Stephen Greenblatt has argued that narratives of discovery, as historical artifacts, actually teach us about the writer rather then the New World. What we witness is not the discovery of The Other—be it place, person, or thing—but rather the experience of the author confronting a radically different world. It is that experience, that confrontation with the unknown that the writers describe.2

The discovery of the New World, in other words, was a discursive act. Europeans used the tools at their disposal—particularly written narrative and cartography—to reveal this unknown world to the peoples of Europe. These texts were an attempt at translation. They described and labeled the New World so that it could be observed, understood, and ultimately possessed by the peoples of the Old World. “The ritual of possession,” Greenblatt argues, “though it is apparently directed toward the natives, has its full meaning then in relation to other European powers when they come to hear of the discovery.”3 In this way narratives of discovery and claims of possession went hand in hand.

Thus, much of what Europeans had to say about the New World had nothing to do with the reality on the ground, but rather was directed toward a European audience. The English, French, and Spanish Empires, for example, all claimed possession of vast territories in North America by right of discovery. This was particularly true for the French Empire. With a small number of settlements situated along the bank of the Saint Lawrence River, the colony of New France laid claim to territory stretching deep into the interior and encompassing the regions we now think of as the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains. In reality, European colonies in seventeenth-century North America consisted of a small number of settlements on the east coast, except for Spain, which controlled the former territory of the Aztecs at the southern tip of the continent. The vast interior of North America remained indigenous. The empires of Europe could, at times, influence the peoples and events in the interior, but most of the continent lay beyond their control, even beyond their comprehension.

To dismiss the idea of discovery as mere political fiction, however, leaves untold a crucial part of the epic story of encounter that defined the early modern world. The New World was, in effect, created through a process of mutual discovery. Just as European empires confronted the implications of discovering a New World, indigenous social formations like the Anishinaabeg were forced to comprehend and incorporate new peoples, animals, tools, weapons, and countless other material artifacts into their social world. In North America these adjustments altered the social relations of production by which human communities sustained themselves. But this encounter had the same effect on the peoples of Europe and Africa. Increasingly, the people, things, and ideas that circulated between their homelands connected human communities on each of these continents. This was the true meaning of the New World: a place of mutual discovery that forced human beings to imagine themselves and their place in the world anew.

To understand the New World and the process of discovery in this way, however, demands a fuller accounting of the history of Native peoples. This, in turn, requires that we rethink the historical archive. If the language of discovery constitutes a literary convention that privileges a European perspective and European social, cultural, and political categories, how do we make sense of the Native peoples that appear in these records? We can begin to answer this question by taking indigenous social formations seriously. This will require that we think about the self-representations of Native peoples as political and diplomatic actors in the era of discovery. And we must recognize that some of the social, political, and cultural constructs and categories used by Native peoples will have no easily translatable equivalent in the social world of Europeans.

Historians of early North American history, like the agents of the English and French Empires, have treated the Iroquois Confederacy as a significant social formation and important political power. This has occurred in large measure because the Iroquois presented European observers with a recognizable social formation. The Iroquois or Haudenosaunee consisted of five culturally related social units, easily recognizable from a European perspective as Native nations, linked as allies in a political confederation governed by commonly accepted laws and religious customs. The political, economic, and military power mobilized by this confederacy resembled the social formations of Europe.

The indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains, however, presented European empires with a different kind of social formation. The peoples of these regions lived largely as hunter-gatherers with a habit of seasonal migration. The patterns of this movement and the social structure that made it possible resulted in a social adaptability that European observers interpreted as politically unformed and culturally primitive. The interactions between these peoples and the empires of Europe have been more difficult to historicize, in large part because European observers struggled to make sense of their social organization and political identity. Nevertheless, the peoples of the Great Lakes constituted a majority among the Native peoples allied to New France, and they constituted a demographic majority in the region they occupied and controlled by virtue of a sophisticated and interlocking system of diplomatic and economic relationships. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries no European empire managed to establish more than isolated outposts in this region.

The fact that Native peoples maintained a demographic majority in the Great Lakes throughout the colonial era makes this region unique. What does this demographic fact say about European claims of discovery and possession? Certainly it raises questions that ask us to go beyond an interrogation of the discourse of discovery. The idea that large Native confederacies like the Iroquois influenced the development of North America permeates most of early American history. But what should we make of the idea that the vast heartland of this continent was occupied and controlled by Native peoples, rather then being possessed by European powers? Should we consider the seasonal migrants of the Great Lakes and the Great Plains to have been political, economic, and military powers in their own right? If so, should this change the way we think and write about the discovery of the New World, and the colonial period in North American history?

In the aftermath of the discovery of the New World, or rather the arrival of European explorers and settlers in inhabited lands, Native peoples nonetheless remained in control of the vast majority of the North American continent. They were not conquered and dispossessed. This stunning fact means that during the colonial era the settler regimes of Europe were surrounded by autonomous Native communities that governed access to the vast majority of the continent’s land and resources. If we acknowledge that the possession of large portions of Native North America by the empires of Europe never occurred, changes must be made to the national narratives of Canada and the United States. But in order to realize the full impact of this history, we must tell it as part of a continental history that traces the simultaneous development of Native and colonial settler social formations in the early modern era.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Place and Belonging in Native North America

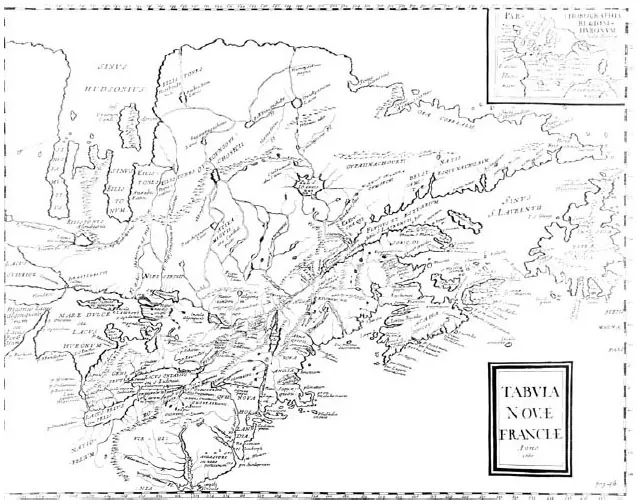

In the spring of 1660 the Anishinaabeg converged on a central location below Gichigamiing (Lake Superior), the largest freshwater lake in North America. They came to a village at another smaller lake, Odaawaa Zaaga’igan (Ottawa Lake, which the French designated as Lac Courte Oreilles). This lake connected two important watersheds, one flowing north into Gichigamiing, the other southwest into the headwaters of Gichi-ziibi (Mississippi), a massive river system that flowed from the heartland of North America into a large ocean gulf that framed the southeastern shoreline of the continent. This village was situated at a crossroad of sorts. It linked the vast grasslands that spread across the interior of North America to the watersheds and lakes that connected the center of the continent to the eastern seaboard (Figure 1). The Anishinaabe bands that lived at the west end of Gichigamiing sent word to the peoples of these regions—other Anishinaabe bands, the Wyandot (Huron) to their east, Muskekowuck-athinuwick (Lowland Cree) peoples from the north, and the Dakotas to their west—that they planned on hosting a ceremony in the spring.1

In the spring people arrived at the Anishinaabe village burdened with the things they valued most in the world. They carried food, animal skins, and peltry fashioned into clothing. They brought wampum, beaded belts made from purple and white shells exchanged as a signifier of alliance or a declaration of war, and used as a ritual gift to mourn the dead. They brought trade goods manufactured by the Europeans who had settled on the east coast of North America. They also carried the bones of their dead ancestors. These things represented the building blocks of a potential exchange network that would link the peoples together in an alliance relationship. This was why they had come together. The Anishinaabeg of Gichigamiing wanted to end the bitter warfare between their community and the Dakota and the Muskekowuck-athinuwick, and replace it with a new relationship. They wanted to end the cycle of raiding and counterraiding that killed off their young warriors, and saw their women and children taken into the villages of their enemies as slaves. To do this they needed to find a way to transform their enemies into allies. In the world of the Anishinaabeg there were two categories of people—inawemaagen (relative) and meyaagizid (foreigner).2

Figure 1. Tabula Novae Franciae [Pere Creuxius] Anno 1660. Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Provincial Archives of Manitoba, G. 5/24 Plate 16 (N15248). This detailed map created from information obtained from Native informants presents the western interior, or Anishinaabewaki, as a complex social space mapped according to Native place-names and self-designations.

The Anishinaabeg needed to find a way to transform their enemies into relatives. To create this new relationship they borrowed a ceremony from the Wyandot, a form of the athataion, or a Feast of the Dead. This Feast of the Dead lasted fourteen days; each filled with dancing, games, gift exchanges, ritual adoption, and arranged marriages between members of the different bands in attendance. The ceremony culminated in a massive eat-all feast where the living dined alongside the corpses of their dead relatives, consumed all the food in the village, and then gave all of the goods that they had accumulated to their guests as gifts. Following the feast, the dead were interred in a common grave.3

The Feast of the Dead ceremony inscribed the past with a new meaning. With the bones of their ancestors joined together, the Anishinaabeg, Muskekowuck-athinuwick, and Dakotas could imagine a shared history of kinship and alliance. Their pasts were buried together. Their futures, in the form of their children—now intermarried—also joined them together as an extended family. Enemies literally and ritually had been transformed into allies by being made into kin. They were now inawemaagen, relatives.

In this way, the Feast of the Dead represented a rebirth. It represented the possibility of uniting a landscape divided by violence and warfare. Relatives shared a sense of responsibility for one another. Along with this responsibility came rights to trade, hunt, fish, harvest rice, and generally sustain the life of the community, all of which were negotiated among the composite parts of a social formation that operated as an extended family. The social relations of production for any Anishinaabe community involved the recognition of reciprocal rights and responsibilities between the different beings (human and other-than-human) occupying a given territory. Alliance expanded the scope of these relationships to include new people and spaces, effectively expanding the physical and social world of the Anishinaabeg.4

In effect, the Feast of the Dead refashioned the rights and responsibilities that defined the relationship between people and landscape. It linked the peoples from the north and south shores of Gichigamiing together, and tied them to the people from the region of Gichi-ziibi, the enormous river valley that drained the forests and grasslands of the interior west. The political and economic integration of these peoples represented a significant reconfiguration of power and space. Joined in alliance, the combined social formations of the Anishinaabeg, the Muskekowuck-athinuwick, and the Dakota possessed the ability to control the circulation of people, animal pelts, and trade goods throughout the heartland of North America. This ceremony, in other words, created an indigenous sociopolitical formation that could, potentially, rival or surpass every other power—Native and European—vying for control of North America’s fur trade. And control of the fur trade translated into power; the power to determine the fate of the Indians and European immigrants struggling to make their place in the New World.

The New World was born of this struggle between Natives and newcomers over place and belonging, and over the rights and responsibilities owed to one another. On a continent that came to be defined by the mass immigration of outsiders, and the wide-scale displacement of the indigenous population, understanding who belonged where, and by what right, are among the most fundamental questions that can be asked or answered. This was what made the Feast of the Dead hosted by the Gichigamiing Anishinaabeg significant in 1660, and this is what makes the story of this event important now.

This ceremony was an act of political self-determination that redrew the boundaries of Anishinaabewaki, Indian country, the homeland of the Anishinaabe peoples. What makes this event remarkable is that it captures a moment of political imagination that represented a rebirth and expansion of Native power and social identity at a time and place usually associated with the expansion of European power. This alone makes the ceremony stand out as a narrative about the history of early modern North America. Reading about the feast we are told a story that cuts against the grain of the usual meanings associated with this period of the continent’s history—stories about the death and diminishment of Native peoples and Native power. But perhaps the story of this Anishinaabe Feast of the Dead only seems remarkable because we know the outcome of Native America’s encounter with the empires of the Atlantic World. That is the central problem of writing the history of North America, vantage point. How to write a history of the New World where it is possible to imagine a Native present, the possibility of a North America that was not entirely consumed by European and then American, Canadian, and Mexican colonization? Begin with a story that all...