- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Formalist Theatre

About this book

Michael Kirby presents a penetrating look a theater theory and analysis. His approach is analytically comprehensive and flexible, and nonevaluative. Case studies demonstrate this unique approach and record performances that otherwise would be lost.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

part one

formalist

analysis

analysis

We have a great heritage In the analysis of dramatic literature, but it is vitally necessary to develop techniques and methods for the analysis of actual presentations. Many continua for the analysis of performance are constructed in this opening part of the book. Its constant focus is on live performance as opposed to and contrasted with dramatic literature. Although some of the concepts developed here may be useful in working with dramatic literature—most of the techniques of structural analysis, for example, may be applied easily to dramatic texts—emphasis is on the spectator rather than the reader. Thus much of the discussion and many of the tools presented here have limited or no application to dramatic literature.

We begin with an analysis of acting itself. Although, as the reference to playscripts by Peter Handke shows, there can be some indication of acting in written texts, the text does not necessarily control or predict the performance. Any script may be interpreted in many ways; the qualities and characteristics of acting can be determined only in the presence of a live presentation. Traditional, literary-oriented approaches have treated the actor as a tool for conveying information. Here, the concern is with the entire range of behavior on stage, whether or not information is involved.

As is made clear in the fourth chapter, the emphasis throughout is on the experience of the spectator. We are not dealing with the way a performance is done—with theatrical technique—but with the perception of the performance. The attempt is to provide something that will be useful not only as philosophy but for the theatre practitioner. Just as literary analysis contributed much to playwriting, performance analysis should contribute to all of the arts of the stage. This is an attempt to examine and analyze the nature of performance itself.

chapter one

acting and not-acting

To act means to feign, to simulate, to represent, to impersonate. As Happenings demonstrated, not all performing is acting. Although acting was sometimes used, the performers in Happenings generally tended to “be” nobody or nothing other than themselves; nor did they represent, or pretend to be in, a time or place different from that of the spectator. They walked, ran, said words, sang, washed dishes, swept, operated machines and stage devices, and so forth, but they did not feign or impersonate.

In most cases, acting and not-acting are relatively easy to recognize and identify. In a performance, we usually know when a person is acting and when not. But there is a scale or continuum of behavior involved, and the differences between acting and not-acting may be small. In such cases categorization may not be easy. Perhaps some would say it is unimportant, but, in fact, it is precisely these borderline cases that can provide insights into acting theory and the nature of the art.

Let us examine acting by tracing the acting/not-acting continuum from one extreme to the other. We will begin at the not-acting end of the scale, where the performer does nothing to feign, simulate, impersonate, and so forth, and move to the opposite position, where behavior of the type that defines acting appears in abundance. Of course, when we speak of “acting” we are referring not to any one style but to all styles. We are not concerned, for example, with the degree of “reality” but with what we can call, for now, the amount of acting.

There are numerous performances that do not use acting. Many, but by no means all, dance pieces would fit into this category. Several Far Eastern theatres make use of stage attendants such as the Kurombo and Kōken of Kabuki. These attendants move props into position and remove them, help with on-stage costume changes, and even serve tea to the actors. Their dress distinguishes them from the actors, and they are not included in the informational structure of the narrative. Even if the spectator ignores them as people, however, they are not invisible. They do not act, and yet they are part of the visual presentation.

As we will see when we get to that point on the continuum, “acting” is active—it refers to feigning, simulation, and so forth that is done by a performer. But representation, simulation, and other qualities that define acting may also be applied to the performer. The way in which a costume creates a “character” is one example.

Let us forsake performance for a moment and consider how the “costume continuum” functions in daily life. If a man wears cowboy boots on the street, as many people do, we do not identify him as a cowboy. If he also wears a wide, tooled-leather belt and even a western hat, we do not see this as a costume, even in a northern city. It is merely a choice of clothing. As more and more items of western clothing—a bandana, chaps, spurs, and so forth—are added, however, we reach the point at which we see either a cowboy or a person dressed as (impersonating) a cowboy. The exact point on the continuum at which this specific identification occurs depends on several factors, the most important of which is place or physical context, and it undoubtedly varies from person to person.

The effect of clothing on stage functions in exactly the same way, but it is more pronounced. A performer wearing only black leotards and western boots might easily be identified as a cowboy. This, of course, indicates the symbolic power of costume in performance. It is important, however, to notice the degree to which the external symbolization is supported and reinforced (or contradicted) by the performer’s behavior. If the performer moves (acts) like a cowboy, the identification is made much more readily. If he is merely himself, the identification might not be made at all.

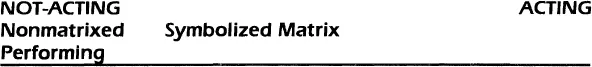

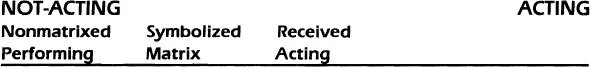

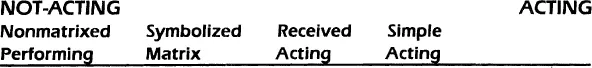

At this stage on our acting/not-acting continuum we are concerned with those performers who do not do anything to reinforce the information or identification. When the performers, like the stage attendants of Kabuki and No, are merely conveyed by their costumes themselves and not embedded, as it were, in matrices of pretended or represented character, situation, place, and time, they can be referred to as being “nonmatrixed.” As we move toward acting from this extreme not-acting position on the continuum, we come to that condition in which the performer does not act and yet his or her costume represents something or someone. We could call this state a “symbolized matrix.”

In Oedipus, a New Work, by John Perreault, the “main performer,” as Perreault refers to him rather than calling him an actor, limps. If we are aware of the title of the piece and of the story of Oedipus, we might assume that this performer represents Oedipus. He does not pretend to limp, however. A stick has been tied “to his right leg underneath his pants in such a way that he will be forced to limp.” When the “main performer” operates a tape recorder, as he does frequently during the presentation, we do not think that this is a representation of Oedipus running a machine. It is a nonmatrixed performer doing something. The lighting of incense and the casting of a reading from the I Ching can be seen as a reference to the Delphic Oracle; the three lines of tape that the “main performer” places on the floor so that they converge in the center of the area can be seen as representing the place where, at the intersection of three roads, Oedipus killed his father, and the limp (and the sunglasses that the “main performer” wears throughout the piece) can be considered to stand for aspects of Oedipus. The performer, however, never behaves as if he were anyone other than himself. He never represents elements of character. He merely carries out certain actions.

In a symbolized matrix the referential elements are applied to but not acted by the performer. And just as western boots do not necessarily establish a cowboy, a limp may convey information without establishing a performer as Oedipus. When, as in Oedipus, a New Work, the character and place matrices are weak, intermittent, or nonexistent, we see a person, not an actor. As “received” references increase, however, it is difficult to say that the performer is not acting even though he or she is doing nothing that could be defined as acting. In a New York luncheonette before Christmas we might see “a man in a Santa Claus suit” drinking coffee; if exactly the same action were carried out on stage in a setting representing a rustic interior, we might see “Santa Claus drinking coffee in his home at the North Pole.” When the matrices are strong, persistent, and reinforce each other, we see an actor, no matter how ordinary the behavior. This condition, the next step closer to true acting on our continuum, we may refer to as “received acting.”

Extras, who do nothing but walk and stand in costume, are seen as “actors.” Anyone merely walking across a stage containing a realistic setting might come to represent a person in that place—and, perhaps, time—without doing anything we could distinguish as acting. There is the anecdote of the critic who headed backstage to congratulate a friend and could be seen by the audience as he passed outside the windows of the on-stage house; it was an opportune moment in the story, however, and he was accepted as part of the play.

Nor does the behavior in received acting necessarily need to be simple. Let us imagine a setting representing a bar. In one of the upstage booths, several men play cards throughout the act. Let us say that none of them has lines in the play; they do not react in any way to the characters in the story we are observing. These men do not act. They merely play cards. They may really win and lose money gambling. And yet we also see them as characters, however minor, in the story, and we say that they, too, are acting. We do not distinguish them from the other actors.

If we define acting as something that is done by, rather than something that is done for or to, a performer, we have not yet arrived at true acting on our scale. “Received actor” is only an honorary title. Although the performer seems to be acting, he or she actually is not. Nonmatrixed performing, symbolized matrix, and received acting are stages on the continuum from not-acting to acting. The amount of simulation, representation, impersonation, and so forth has increased as we have moved along the scale, but, so far, none of this was created by the performer in a special way we could designate as “acting.”

Although acting in its most complete form offers no problem of definition, our task in constructing a continuum is to designate those transitional areas in which acting begins. What are the simplest characteristics that define acting?

They may be either physical or emotional. If the performer does something to simulate, represent, impersonate, and so forth, he or she is acting. It does not matter what style is used or whether the action is part of a complete characterization or informational presentation. No emotion needs to be involved. The definition can depend solely on the character of what is done. (Value judgments, of course, are not involved. Acting is acting whether or not it is done “well” or accurately.) Thus a person who, as in the game of charades, pretends to put on a jacket that does not exist or feigns being ill is acting. Acting can be said to exist in the smallest and simplest action that involves pretense.

Acting also exists in emotional rather than strictly physical terms. Let us say, for example, that we are at a presentation by the Living Theatre of Paradise Now. It is that well-known section in which the performers, working individually, walk through the auditorium speaking directly to the spectators. “I’m not allowed to travel without a passport,” they say. “I’m not allowed to smoke marijuana!” “I’m not allowed to take my clothes off!” They seem sincere, disturbed, and angry. Are they acting?

The performers are themselves; they are not portraying characters. They are in the theatre, not in some imaginary or represented place. What they say is certainly true. They are not allowed to travel—at least between certain countries—without a passport; the possession of marijuana is against the law. Probably we will all grant that the performers really believe what they are saying—that they really feel these rules and regulations are unjust. Yet they are acting. Acting exists only in their emotional presentation.

At times in real life we meet people who we feel are acting. This does not mean that they are lying, dishonest, living in an unreal world, or necessarily giving a false impression of their character and personality. It means that they seem to be aware of an audience—to be “on stage”—and that they react to this situation by energetically projecting ideas, emotions, and elements of their personality, underlining and theatricalizing it for the sake of the audience. That is what the performers in Paradise Now were doing. They were acting their own emotions and beliefs.

Let us phrase this problem in a slightly different way. Public speaking, whether it is extemporaneous or makes use of a script, may involve emotion, but it does not necessarily involve acting. Yet some speakers, while retaining their own characters and remaining sincere, seem to be acting. At what point does acting appear? At the point at which the emotions are “pushed” for the sake of the spectators. This does not mean that the speakers are false or do not believe what they are saying. It merely means that they are selecting and projecting an element of character—emotion—to the audience.

In other words, it does not matter whether an emotion is created to fit an acting situation or whether it is simply amplified. One principle of “method” acting—at least as it is taught in this country—is the use of whatever real feelings and emotions the actor has while playing the role. (Indeed, this became a joke; no matter what unusual or uncomfortable physical urges or psychological needs or problems the actor had, he or she was advised to “use” them.) It may be merely the use and projection of emotion that distinguishes acting from not-acting.

This is an important point. It indicates that acting involves a basic psychic or emotional component; although this component exists in all forms of acting to some degree (except, of course, received acting), it, in itself, is enough to distinguish acting from not-acting. Since this element of acting is mental, a performer may act without moving. This does not mean that, as has been mentioned previously, the motionless person “acts” in a passive and “received” way by having a character, a relationship, a place, and so on imposed on him by the information provided in the presentation. The motionless performer may convey certain attitudes and emotions that are acting even though no physical action is involved.

Further examples of rudimentary acting—as well as examples of not-acting—may be seen in the well-known “mirror” exercise in which two people stand facing each other while one copies or “reflects,” like a mirror, the movements of the other. Although this is an exercise used in training actors, acting itself is not necessarily involved. The movements of the first person, and therefore those of the second, might not represent or pretend. Each might merely raise and lower the arms or turn their head. The movements could be completely abstract.

It is here, however, that the perceived relationship between the performer and what is being created can be seen to be crucial in the definition of acting. Even “abstract” movements may be personified and made into a character of sorts through the performer’s attitude. If the actor seems to indicate “I am this thing” rather than merely “I am doing these movements,” we accept him or her as the “thing”: the performer is acting. But we do not accept the “mirror” as acting, even though that character is a “representation” of the first person. He lacks the psychic energy that would turn the abstraction into a personification. If an attitude of “I’m imitating you” is projected, however—if purposeful distortion or “editorializing” appears rather than the neutral attitude of exact copying—the mirror becomes an actor even though the original movements were abstract.

The same exercise may easily involve acting in a more obvious way. The first person, for example, may pretend to shave. The mirror, in copying these feigned actions, becomes an actor now in spite of taking a neutral attitude. (We could call the mirror a “received actor” because, like character and place in our earlier examples, the representation has been “put upon” that person without the inner creative attitude and energy necessary for true acting. The mirror’s acting, like that of a marionette, is controlled from the outside.) If the originator in the mirror exercise put on a jacket, he or she would not necessarily be acting; if the originator or the mirror, not having a jacket, pretended to put one on, it would be acting, and so on.

As we have moved along the continuum from not-acting to acting, the amount of representation, personification, and so forth has increased. Now that we have arrived at true acting, we might say that it, too, varies in amount. Small amounts of acting—like those in the examples that have been given—would occupy that part of the scale closest to received acting, and we could move along the continuum to a hypothetical maximum amount of acting. Indeed, the only alternative would seem to be an on-off or all-or-nothing view in which all acting is theoretically (if not qualitatively) equal and undifferentiated.

“Amount” is a difficult word to use in this case, however. Since, especially for Americans, it is easy to assume that more is better, any r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Formalist Analysis

- Part Two: The Social Context

- Part Three: Structuralist Theatre

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Formalist Theatre by Michael Kirby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.