![]()

Chapter 1

First Impressions

The Presse, the most-honorable Presse, the most-villainous Presse

—Gabriel Harvey (1593)

Prologue: Some Foundation Myths

Let me start with some of the foundation myths that reveal long-lasting attitudes toward printing on the part of Western Europeans. They concern Gutenberg's one time partner, Johann Fust (sometimes spelled Faustus). He helped to subsidize the operations of the Mainz press, and his daughter married Peter Schoeffer, who fathered the first Mainz printing dynasty. Thus, there is good reason to consider him as a founding father of the new industry.

The mythic dimension is supplied by the long-lived confusion between Johann Fust, who died in 1466, and the necromancer “Doctor” Johann Georg Faustus, whose life provided the prototype for the Faustbuch and who was born around 1480.1

According to the anticlerical author of an eighteenth-century dictionary, Fust was wrongly confused with “one Johann Faust, a fraudulent magician” owing to “lies circulated by monks who hated anyone associated with the invention of printing.”2 A nineteenth-century biographical dictionary provides a different, more detailed version:

FUST, or FAUSTUS (JOHN) a citizen of Mainz and one of the earliest printers. He had the policy to conceal his art; and to this policy we are indebted for the tradition of “The Devil and Dr. Faustus,” handed down to the present times. About 1460, he associated with John of Guttemburgh…and…having printed off a…number of copies of the Bible, to imitate those which were commonly sold in MS, Fust undertook the sale of them in Paris, where the art of printing was then unknown. As he sold his printed copies for 60 crowns while the scribes demanded 500, this created universal astonishment: but when he produced copies as fast as they were wanted and lowered the price to 30 crowns, all Paris was agitated. The uniformity of the copies increased the wonder; informations were given in to the police against him as a magician;…a great number of copies being found [in his lodgings], they were seized; the red ink with which they were embellished was said to be his blood; it was seriously adjudged that he was in league with the devil; and if he had not fled, most probably he would have shared the fate of those whom ignorant and superstitious judges condemned…for witchcraft.3

Whereas the first version took for granted the hostility of monks (a common misconception even now), this one depicts a mystified urban populace. It takes note of the sudden rise in output, drop in price, and uniformity of copies which led contemporaries to suspect magic. In view of recent assertions that the handpress was incapable of standardizing texts and that uniformity came only in the nineteenth century, it's worth citing the early eighteenth-century version of a similar tale by Daniel Defoe:

the famous doctors of the faculty at Paris, when John Faustus brought the first printed Books that had been seen in the World or at least had been seen there, in to the City and sold them for Manuscripts: They were surprized…and questioned Faustus about it; but he kept affirming that they were manuscripts and that he kept a great many Clarks employ'd to write them thus satisfying his questioners for a while. But then they observed the exact agreement of every Book one with another, that every line stood in the same place, every page [had] a like Number of lines, every line, a like number of words; if a word was misspelled in one, it was misspelled also in all; nay, that if there was a Blot in one, it was alike in all; they began again to muse, how this should be…not being able to comprehend the Thing…[they] concluded it must be the Devil, that it was done by Magic and Witchcraft…[and that]…poor Faustus (who was indeed nothing but a meer Printer) dealt with the Devil…[This is the] true original of the famous Dr. Faustus…of whom we have believed such strange things…whereas poor Faustus was no Doctor and knew no more of the Devil than any other body.4

Defoe, who certainly knew his way around printing shops, thus held the handpress capable of the sort of standardization that recent critics have deemed impossible.5 He also reflected the superior attitude of an eighteenth-century writer who treated belief in magic and witchcraft as evidence of ignorance about the actual workings of a machinery behind the scenes. In his account, however, ignorance was deliberately cultivated by the secretive bookseller who pretended his products had been hand-copied.

In the tales of Fust-cum-Faustus, the duplicative powers of print are mistaken for magic by the uninitiated.6 Different attributes, entailing expropriation and exploitation, also became associated with Gutenberg's onetime partner. Long after printing had ceased to be viewed as a magical art, it continued to be stigmatized as a mercenary métier. Johann Fust was less and less likely to be accused of sorcery, but more and more likely to be viewed as an exploitative capitalist who robbed an unworldly, impractical inventor of the fruits of his labor.7 In this instance, the wordplay is not on the variant spelling of Fust as Faust but on the meaning of “Fust” as “fist”—as something that is, by its nature, “grasping.”8 To cite a standard nineteenth-century reference work: “greedy, crafty, and heartless speculator, who took a mean advantage of Gutenberg's necessity, and robbed him of his invention.”9 This mythic Fust has recently been described by a Marxisant literary critic as embodying Western printing's primal crime. In her view, the document attesting to the lawsuit that Fust won against Gutenberg (the most valuable piece of evidence concerning the Mainz invention) points to the “legitimation” of the capitalistic control of the book trade: “capital, comes to control the book trade and the skilled labor of printers and writers alike.”10 In another version, industrial sabotage is at work. The poor inventor who was robbed turns out to be, not the “German” Gutenberg of Mainz, but the “Dutchman” Lawrence Hans (Laurens Coster) of Haarlem, who was robbed “on a Christmas daye att night, of all his instrumentes by John Faustus who fled to Mentz in Germany.”11

The split identity of the inventive craftsman/thieving financier is a remarkably persistent feature of Western literature on printing. It reappears in the eighteenth-century good author/bad bookseller fiction (with the gifted

author replacing the inventive artisan as a victim of the exploitative bookseller). It is elaborated in more recent studies of the “social history of ideas.”12 Despite the well-documented existence of commercial copying centers before Gutenberg's day, the sinister figure of the exploitative capitalist appears to have no equivalent in stories about scribes and copyists.13 It makes its debut only after the advent of printing, when would-be authors became reliant on “the commercial judgment of publishers to establish their place in the world of letters.”14 It looms ever larger as the centuries progress until it merges with antisemitic propaganda during the Dreyfus years, when Fust (who came of Christian burgher stock) gets recast as a usurious Jew.15

We need not wait for centuries to pass to encounter complaints about the sharp dealings of the greedy printer or profiteering merchant/publisher. But such complaints should not be mistaken, as they frequently are, for a repudiation of the craft itself. More often than not, they were directed only at the shortcomings of certain practitioners. When medieval anticlerical writers condemned the lechery or gluttony of monks who fell short of embodying an ascetic ideal, they took a different position from that of eighteenth-century philosophers who rejected “penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, solitude, and the whole train of monkish virtues.”16 Similarly there is a difference between objecting to error-filled editions and repudiating the art of printing. When Conrad Leontorius attacked ignorant and careless printers, he was not rejecting the “divine art,” as he called it, but rather deploring the way it was being mistreated. He went on to compliment his friend Johann Amerbach on his superior products.17

Initial Reactions: Pros and Cons

This brings me to the question that the rest of this chapter will explore: how did Gutenberg's contemporaries and immediate successors react to the advent of printing? The question has received different and often contradictory answers. According to Paul Needham,

The invention of printing made a striking impression on the literate minds of the time…historians are often tempted to produce an artificially “balanced” view…by arguing that to contemporary eyes, the new invention held both advantages and disadvantages; or that printed books infused themselves so gradually into the European world that no dramatic date of cultural change can be identified…it is abundantly clear that from the earliest days of their appearance, printed books were considered and accepted as a great success in their own right, that is, as more than an ersatz for manuscripts.18

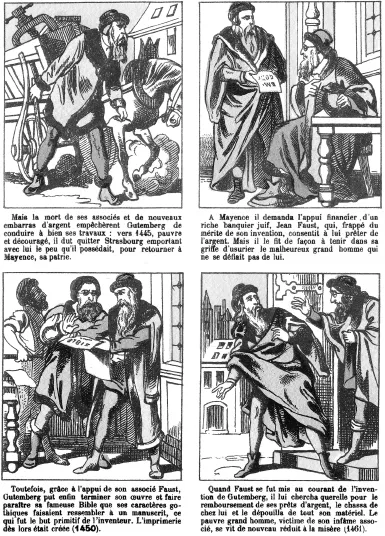

Figure 1.1. Details from Image d'Epinal #382 (1890). Gutenberg travels from Strasbourg to Mainz to get financing for his invention from Johann Faust. The Jewish banker supports printing the Mainz Bible, then bankrupts the inventor and confiscates his equipment. Courtesy of the Musée National de l'Education.

The two separate issues that are intertwined in this citation need sorting out. Whether printing “made a striking impression” from the first is a different matter from whether the invention was invariably accepted as a “great success.” On this last point Needham's verdict seems to be too sweeping, even though citations from the writings of contemporaries seem to bear him out.

Thus, a letter of 1455 written to a Spanish cardinal by a future pope about seeing unbound quires of a printed Bible (probably the forty-two-line Gutenberg Bible) conveys both an immediate and highly favorable impression. The text was exceedingly clean, wrote Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini. It was without error and could be read without glasses. Several people reported that over one hundred copies were finished.19 This letter has the additional significance of showing that the printing of a sacred text was welcomed without any reservations by highly placed churchmen. A different social position was occupied by the Venetian physician Nicolaus Gupalatinus. He also took a favorable view. He persuaded the first native-born Italian printer to print a medical treatise and described the press as a “miracle worth celebrating, one unknown to all previous ages.”20

I agree with Needham that the “artificially balanced” view presented by many authorities does not do justice to the initial enthusiasm that was exhibited by such individuals. Division of opinion over the invention often gets concocted, seemingly out of thin air, with “triumphalist” accounts set against imaginary “catastrophist” ones.21 Of course, opinions were likely to vary, depending on the position of those who expressed them. Churchmen, scholars, and book hunters were unlikely to share the same outlook as manuscript dealers or professional scribes and illuminators. The latter groups are often thought to be opponents of the new art on the mistaken assumption that printing deprived them of their livelihood. But, on the contrary, they were kept busier than ever. The demand for deluxe hand-copied books persisted, and the earliest printed books were hybrid products that called for scribes and illuminators to provide the necessary finishing touches.22

“There was an immense range of individual opinions,” writes Martin Lowry, “all can be placed somewhere between committed acclamation and absolute rejection.”23 Even this seemingly cautious assessment still tends to obscure Needham's point that there was an actual imbalance—that acclamation outweighed rejection.

Indeed, there is little evidence of absolute rejection. The foundation myths that depict hostile monks and urban crowds making accusations of witchcraft, profiteers engaged in industrial sabotage, or scribes deprived of their livelihood seem to be baseless. It's true that Fran

ois I temporarily banned printing after the affair of the placards, and two colonial governors in seventeenth-century Virginia banned printing from that colony.

24 But neither episode had much effect, and neither occurred in the fifteenth century.

There is little or no evidence of absolute rejection in the fifteenth century, while there is much evidence of “committed acclamation.” Nevertheless, fifteenth-century commentators were not always single-minded about the new presses. Initial enthusiasm can be documented, but so can subsequent disillusion and disappointment. The fifteenth-century scholar who wrote that he sometimes “wondered whether printing was a blessing or a curse”25 was not a figment of a later imagination. Nuances get lost when one cites, as Needham does, only favorable comments without pausing over negative ones. As later discussion suggests, negative views are not hard to find. Indeed, a “protracted debate…on whether the new art was a force for good or for evil” has been discerned by Brian Richardson.26 The existence of negative views is not in doubt. What needs more attention is that such views were most often directed not at the new art itself but rather at its unworthy practitioners. This was especially the case with authors who often regarded printers, much as earlier writers had regarded copyists, with considerable ambivalence.

On the other question, of gradual infusion as opposed to dramatic change, Needham's view seems to be sustained by unambiguous evidence. The future pope and the Venetian physician cited above were by no means alone. An admiring comment about a wonderfully efficient new technique for reproducing books was made in 1466 by Leon Battista Alberti.27 Martin Lowry describes Venetian literati as being disoriented and “thrown into complete disarray” by the advent of printing.28 His account has persuaded others that the sudden increase in output stunned contemporaries, “almost literally overwhelming them.”29 Thus it does seem “abundantly clear” that the invention made an immediate and striking impression, at least upon literati.

Nevertheless, there are book historians who argue that the impression first made by the new technology was so faint as to be almost imperceptible. According to a favorable review of Silvia Rizzo's study, for example, the author “shows convincingly…that in the mind of the humanists there was no distinct line of demarcation between the manuscript book and that printed by movable type.”30 As is often the case when dealing with the shift from script to print, one is presented with two seemingly incompatible models of change. For Rizzo, the change was so gradual that it almost went unnoted. For Needham, it was so marked that it aroused immediate comment. Different kinds of evidence are presented to substantiate these different views.

The arguments favoring gradualism tend to pass over fifteenth-century reports of excited comment while stressing the similar uses that were initially made of hand-copied and printed books. Whereas manuscripts and printed products are now assigned to separate categories by curators and dealers, fifteenth-century readers found both kinds of books for sale in the same locales, often in the same shops. Purchasers placed them together in the same cabinets or on the same shelves and sometimes had them covered by the same bindings. The contrast with twentieth-century practices is striking and helps to explain why authorities insist that “the fifteenth century…made little distinction between hand-written and press-printed books.”31 Moreover, during the fifteenth century a carryover of format and layout reinforced the impression of similarity. When discussing a particular text, readers did not always make clear whether it was hand-cop...