![]()

Part I

The Regional Context

![]()

Chapter 1

The Geopolitics of the Great Lakes Region

In common usage the Great Lakes region refers to Central Africa's Great Rift valley, stretching on a north-south axis along the Congo-Nile crest, from Lake Tanganyika in the south to Lake Edward and the legendary Mountains of the Moon in the north. But where exactly does it begin, and where does it end? Should it include western Tanzania and southwestern Sudan? Should the Maniema and north Katanga be factored in as well? The answers are anything but straightforward. There is general agreement, however, that a minimal definition should include Rwanda, Burundi, eastern Congo, and southwestern Uganda as the core area of what once was called the “interlacustrine” zone of the continent, covering an estimated 300,000 square miles. This is the sense in which we shall use the phrase.

The interlacustrine metaphor, though still fashionable among geographers, suggests too much in the way of uniformity and too little about the diversity of peoples, cultures, and subregions subsumed under this label.1 There is a fundamental truth in the observation that “the extent to which people are attached to their native turf (terroir d'origine) is still highly developed among the people of the Great Lakes.”2 To this day, group loyalties continue to cluster around precolonial terroirs. Whereas many readily identify with places like Nduga, Kiga, Bwisha, Bwito, Masisi, Rutshuru, Beni-Butembo, to name only a few, nowhere among Africans is the Great Lakes referent perceived as a meaningful identity marker. The phrase, as Jean-Pierre Chrétien reminds us, is evocative of “the German tradition of a Volkgeist, as if a kind of common soul had emerged from the proximity of these lakes.”3 Though encompassing many of the shared cultural traits identified by the French historian—a high population density, the agropastoral tandem, the heritage of kingship, a tendency for outsiders to look at these societies through the lens of race, and so forth—in the end, he adds that what links these peoples and cultures together is “a kind of connivance born of multiple confrontations and countless encounters.”4 Since these words were written (1986), most of these encounters have been extremely bloody and their after-effects, devastating.

At the root of these confrontations lies an array of forces and circumstances of enormous complexity. Most are the product of human decisions made during the colonial and postcolonial eras, but these must be seen in the perspective of the drastic changes that have taken place in the regional environment. Politics and geography intersect in different ways at different points in time, but the key variables remain the same. The potential for conflict is inscribed in the discontinuities in population densities, the availability of land, the cultural fault lines discernible in different language patterns, modes of social organization, and ecological circumstances. None of the above were fixed from time immemorial. As has been noted time and again, most recently by Michael Mann, modernity has gone hand in hand with eruptions of ethnic violence.5 Societies that were once held together by hierarchies of birth, rank, and privilege have been subjected to profound disruptions of their social fabric, ushering in “masterless men,”6 marginalized youth, and warlords in search of gold, diamonds, and coltan. Today's demographic explosion in Rwanda, resulting in a population density of 300 per square kilometer, is without parallel elsewhere, causing a drastic shrinking of cultivable land; areas where land hunger was almost unknown at the inception of colonial rule (as in Rutshuru and Masisi) are now saturated; deforestation has denuded large tracts of land, accelerating soil erosion and reducing crop cultivation;7 almost everywhere wildlife is fast disappearing, most notably hippos, elephants, and mountain gorillas, with profoundly negative effects on the region's ecosystem.8 Once described as a tourist paradise,9 today's Great Lakes region shows many of the symptoms of a Hobbesian universe.

Convenient though it is to speak of the crisis in the Great Lakes in the singular, it makes more sense to think in terms of a multiplicity of crises, which, though historically distinct and occurring in specific national contexts, have set off violent chain reactions in neighboring states. The Hutu revolution (1959–62) in Rwanda was one such crisis. Another was the 1994 genocide. Both have sent shock waves through the region the first creating the conditions of a “partial genocide” of Hutu in Burundi in 1972, the second unleashing ethnic cleansing, population displacements, and civil war through many parts of the Congo, resulting in human losses far greater than in either Burundi in 1972 or Rwanda in 1994. To these we shall return in a moment, but before going any further, a note of caution is in order about some of the misconceptions surrounding the region's recent agonies.

Challenging Received Ideas

The belief that nowhere in the continent has violence taken a heavier toll than in Rwanda, with nearly a million deaths, overwhelmingly Tutsi, is one of the most persistent and persistently misleading ideas about the region. It may come as a surprise, therefore, that four times as many people have died in eastern Congo between 1998 and 2006. Although the exact number will never be known, a recent survey by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) shows that nearly four million people were killed from war-related causes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since 1998, “the largest documented death toll in a conflict since World War II.”10 Citing the IRC survey, the British medical journal The Lancet recently drew the right conclusion: “It is a sad indictment of us all that seven years into this crisis ignorance about its scale and impact is almost universal, and that international engagement remains completely out of proportion to humanitarian need.”11

Ignorance in this case is largely a reflection of public indifference in the face of a situation that, however unfortunate, is generally seen by outside observers as African-made, rooted in the incorrigible greed of rival warlords and therefore, the responsibility of Africans. But this is only partially true. This is how a British journalist sees the other side of the coin in his coverage of “the most savage war in the world”: “it is also the story of a trail of blood that leads directly to you: to your remote control, to your mobile phone, to your laptop and to your diamond necklace…it is a battle for the metals that make our technological society vibrate and ring and bling.”12 Western economic interests are indeed deeply involved in the conflict through their participation, direct or indirect, in the illicit trade in arms and mineral resources. Both span a wide network of companies, brokers, money changers, and facilitators. European companies—Belgian (Cogecom), Swiss (Finmining, Raremet), German (Masingiro), Dutch (Chemie Pharmacie)—figure prominently in the war economy of the region, a fact conclusively demonstrated by several outstanding investigative reports.13 Among various forms of the involvement of the United States, passing reference must be made to the joint venture between the American corporation Trinitech and the Dutch firm Chemie Pharmacie, in which the U.S. embassy in Kigali may have played a “facilitating” role. As reported by one well-informed observer, “the economic section of the U.S. embassy in Kigali has been extremely active at the beginning of the war in helping establish joint ventures to exploit coltan,” a fact carefully expunged from all official reports, leaving only Africans to be incriminated.14 Though seldom brought into the public domain, the share of responsibility of Western corporate interests in supporting a war economy that has resulted in the deaths of millions, cannot be ignored.

Frequent reference to confrontations among warring factions as a “resource war” points to yet another misconception, for which Paul Collier deserves full credit.15 This is not to imply that “greed” is not a factor in sustaining the bloodshed; the point rather is that it never played the central role that Collier would like us to believe in setting in motion the infernal machine leading to interethnic and interstate violence. As recent academic research has shown, instead of invoking the logic of self-serving enrichment, the denial of economic opportunities, more often than not as a result of political exclusion, emerges as the critical factor in the etiology of conflict.16 The basic distinction here is between exclusion as the initial motive and greed as a propelling force at a later stage of intergroup violence. The passage from exclusion to greed is not automatic; it implies major changes in the regional field of politics that also point to basic shifts in identity patterns.

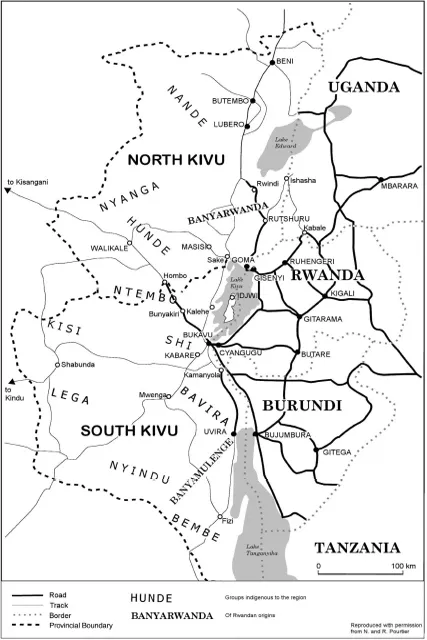

Map 1. Ethnic map of North and South Kivu. Reproduced from Roland Pourtier, “Cong-Zaire-Congo: Un itinéraire géoplitque au coeur de I'Afrique,” Hérodote, nos. 86/87 (1997): 22, by permission of the author.

Deconstructing Social Identities

Tempting as it is to view ethnic diversity as the central determinant of violent behavior in the region, the evidence shows otherwise. To the extent that it does provide a meaningful point of reference, ethnicity is not a throwback to primeval enmities. Whether socially constructed, manipulated, invented, or mobilized, it is a recent phenomenon, even when its roots are sometimes traceable to precolonial times (as in the case of the Banyamulenge). Its contours, moreover, are constantly shifting, as are the human targets against which it is directed. Communities seen as allies one day are viewed as enemies the next. New coalitions are built for short-term advantage, only to dissolve into warring factions when new options suddenly emerge. In this highly fluid political field, conflict is not reducible to any single identity marker. It is better conceptualized as involving different social boundaries, activated at different points in time, in response to changing political stakes.

HUTU VERSUS TUTSI: THE REDUCTIONIST TRAP

No serious analyst of the recent history of the Great Lakes would deny the central significance of the Rwanda genocide on the polarization of Hutu-Tutsi identities throughout the region. Nonetheless, to reduce every conflict at every stage of its evolution to a straight Hutu-Tutsi confrontation is unconvincing. Such a dualism overlooks the presence of alternative forms of identification and wrongly assumes the salience of the Hutu-Tutsi dichotomy to be a permanent feature of the political landscape.

The danger of Hutu-Tutsi reductionism is all the more evident when one considers the ethnographic composition of the region. Rwanda and Burundi, after all, are not the only countries whose ethnic maps reveal the existence of Hutu and Tutsi. Kinyarwanda or Kirundi-speaking people also are found in eastern Congo, southern Uganda, and western Tanzania. According to the best estimates, the region claims roughly twelve million people speaking Kinyarwanda, and nearly twenty million if Kirundi, a language closely related to Kinyarwanda, is included. Although many migrated from Rwanda and Burundi to neighboring states during and after the colonial period, the presence of Hutu and Tutsi in eastern Congo reaches back to precolonial times. What needs to be underscored is that migrations from Rwanda or Burundi did not occur only one time but were staggered through the centuries. Length of residence, ecology, and history have shaped identities in ways that defy simple categorizations such as Hutu and Tutsi. It is with reason, therefore, that some analysts, in coming to grips with the politics of North Kivu, insist on drawing distinctions between the Hutu from Bwisha, those from Rutshuru, and those from Masisi and Kalehe.17

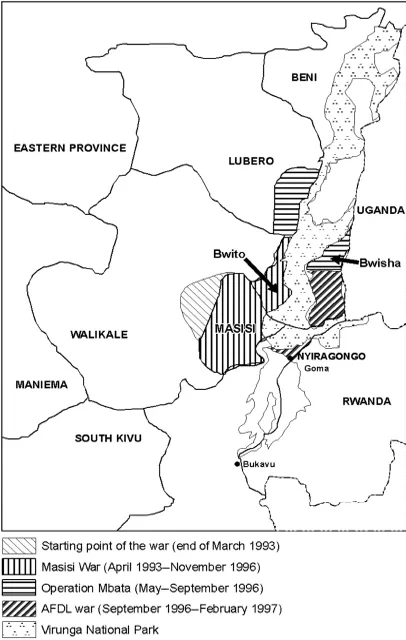

Map 2. Areas of confrontation in North Kivu. Reproduced from F. Reyntjens and S. Marysse, eds., L' Afriquw des Grands Lacs: Annuaire 2005–2006 (Paris: L'Harmattan, 2006), p. 37, by permission of the editors.

Such nuances went largely unnoticed by Belgian civil servants. In its effort to make more “legible,” the complex ethnic configurations of the region, the colonial state contributed significantly to formalizing and legitimizing the Hutu-Tutsi polarity. Thus the 1959 census figures for what was then the Kivu region (now divided into North and South Kivu and Maniema) designate, oddly enough, as “Bantous Hamites” and “Hamites,” respectively, the 184,089 Hutu and 53,233 Tutsi registered, thus making the “Banyarwanda” the third-largest group after the Banande (390,704) and the Bashi (382, 572).18 Time and again historians have drawn attention to the perverse effects of the colonizer's recourse to Hamitic and Bantu labels, as if to impose its own normative construction on Hutu and Tutsi.19 Equally striking is the phenomenon described by James Scott in Seeing Like a State, namely, “the state's attempt to make a society legible, to arrange the population in ways that simplified the classic state functions.” These state simplifications, he adds, “did not successfully represent the actual activity of the society they depicted, nor were they intended to…they were maps that, when allied with state power, would enable much of the reality they depicted to be remade.”20

Nonetheless, such attempts at remaking social realities did not obliterate all distinctions within Hutu and Tutsi. Nor did they erase the persistent tension between them, on the one hand, and the so-called “native” Congolese on the other. Many Kinyarwanda speakers, Hutu and Tutsi, trace their families' origins to precolonial times and have every right to claim the status of Congolese citizens. This is certainly true of the Banyamulenge (“the people from Mulenge”) established in the high plateau area of South Kivu since the nineteenth century if not earlier,21 and of the Hutu of Bwisha, many of whom lived in this area long before the onset of colonial rule, whereas others came as agricultural laborers from Rwanda in the 1930s to supply the European plantocracy of North Kivu with cheap labor. In short, as social categories, the terms “Hutu” and “Tutsi” cannot do justice to the registers of historical experience that lie at the heart of these many subloyalties.

THE CASE OF THE BANYAMULENGE

A rather unique case of ethnogenesis, the Banyamulenge are a perfect example of how geography, history, and politics combine to create a new set of identities within the larger Banyarwanda cultural frame.22 Heavily concentrated on the high-lying plateau of the Itombwe region of South Kivu, estimates of their numerical importance vary wildly. The figure of 400,000 cited by the late Joseph Muembo is grossly inflated.23 A more reliable figure would be between 50,000 and 70,000. Their name derives from the locality (Mulenge) whence they are said to originate. The term, however, has been the source of much controversy because it became increasingly used in the late 1990s as an omnibus label to designate all Tutsi living in North and South Kivu. It came into usage in 1976 as a result of the efforts of the late Gisaro Muhoza, a member of parliament from South Kivu, to regroup the Banyamulenge populations of Mwenga, Fizi, and Uvira territories into a single administrative entity. Although his initiative failed, the name stuck, and by 1996 it was often used by ethnic Tutsi and Congolese to designate all Tutsi residents of North and South Kivu.

Though much of their history is shrouded in mystery, most historians would agree that the Banyamulenge are descendants of Tutsi pastoralists who migrated from Rwanda some time in the nineteenth century, long before the advent of colonial rule (a fact vehemently contested, however, by many Congolese intellectuals). They are culturally and socially distinct from the long-established ethnic Tutsi of North Kivu and the Tutsi refugees of the 1959–62 Rwanda revolution. Many do not speak Kinyarwanda, and those who do, speak it differently. Their political awakening can be traced back to the eastern Congo rebellion of 1964–65. Many initially joined the insurgency, only to switch sides when they saw their cattle being slaughtered to feed the insurgents. Their contribution to the counterinsurgency did not go unnoticed in Kinshasa. Many were rewarded with lucrative positions in the provincial capital, and more and more of their children flocked to missionary schools. From a primarily rural, isolated, backward community, the Banyamulenge would soon become increasingly aware of themselves as a political force.

It is impossible to tell how many joined the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) in the 1990s. What is beyond doubt is that they formed the bulk of Kabila's Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo (AFDL) in 1996 and after the fall of Bukavu, they filled most of the administrative positions vacated by the Congolese, some of whom were ardent Mobutists. Equally clear is that they suffered very heavy losses during the anti-Mobutist crusade, as well as during the 1998 crisis when many were massacred by Kabila's supporters in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi. It was said that in the late 1990s, Bukavu claimed a larger number of Banyamulenge widows than any other town in the region.

The creation in mid-1998 of the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (RCD), under Rwandan sponsorship, was meant to provide the Banyamulenge with a vehicle for the defense of their interests—and of anyone else's who cared to join—but as it evolved into an instrument for the defense of Rwandan interests in eastern Congo, many felt aggrieved and alienated. The feeling that they have been “instrumentalized” by Kagame is shared widely among them. As we shall see, this sense of grievance against Rwanda is in large part responsible for the internal strains and divisions suffered by the community. All this, however, does not detract from the fact that as a group, the Banyamulenge are profoundly aware of their cultural distinctiveness. Few people have been dealt a harsher blow by history: many argue, with justice, that they have been twice victimized; first by Kagame, who used them as cannon fodder for the defense of Rwanda's strategic interests; and then by Congolese extremists, as happened in Bukavu in June 2004 when in the wake of an abortive Banyamulenge-led coup, hundreds perished. Today Bukavu is virtually “free” of Banyamulenge.

OTHERNESS

What defines the “other” as an ally or an enemy? Several objective criteria come to mind: language (e.g., “Rwandophones” or Kinyawanda speakers), country of origin (“Banyarwanda”), place of settlement (“Banyamulenge,” the people of Mulenge), ethnicity (Hutu and Tutsi), to which must be added morphologie, or body maps, a reference that increasingly crops up in newspaper articles in Goma and Bukavu. None of the above, however, tells us why one set of...