![]()

CHAPTER 1

Setting Up

In 1700, the village of Osu amounted to fewer than a hundred family compounds spread out along rows of trees and broad paths that led down to the beach and the Danish fort. The clay and thatched dwellings consisted of smaller huts arrayed around interior courtyards, with long roofs that extended over the street; during the heat of the day people sat beneath them on clay benches, watching the comings and goings in the village. In the morning and again in the evening, Ga women carried their goods and foodstuffs to and from their stalls in the market square, from which they sold fresh, dried, salted, and cooked fish; palm wine; kenkey, fufu, or other prepared meals; and cloth and beads. Almost all the sellers in the market were women. They were renowned for their skill and industry as traders, and people came from near and far to the market. Some buyers were villagers or people from nearby towns on the coast. Others were farmers from farther inland, bringing baskets of oranges, limes, bananas, sweet potatoes and yams, millet, maize, rice, pepper, chickens, eggs, bread, and other foodstuffs, which they exchanged for fish or European products that could be found only on the coast. A final small group of buyers were white men from the Danish fort down on the beach.1

Perhaps Koko Osu and her friends watched when Frantz Boye arrived in Osu in February 1700. It was only a short walk from their compounds to the beach, where fishermen’s canoes rested and where Europeans would land after months of sailing. European ships did not come in often, so it was a big event when they did. Koko would have known about Europeans. Her father, Tette Osu, was a powerful man; the Europeans called him caboceer,2 and he made a living trading with them. Maybe Koko and her friends sat on the warm cliffs and watched as the men stepped out of the canoes and onto the beach for the first time. Perhaps they compared notes and made bets about which among the new arrivals would survive the longest in Africa. Far from all Europeans made it. Some stayed only until the next ship left the coast, many got sick, and some died.3

Koko was cassaret to Frantz not many years after that. Tette Osu had probably concluded that Frantz would be a good trading ally, which he was, but the marriage was at least as important for the Dane. Over the next decades he did extremely well in Africa. Surviving on the coast was itself an achievement that could mean rapid advancement, but marrying into one of the most powerful trading families in Osu also helped. After a few years Frantz was promoted to assistant and sent on expeditions on behalf of the Danish West India and Guinea Company, carrying messages and presents to the king of Akwamu. Within six years he was appointed chief assistant at the fort, and by the time he was appointed governor in 1711 he was well acquainted with several African languages, as well as the Portuguese lingua franca of the coast. By that time Koko and Frantz had one child together, who was followed by another, a son who bore the very Danish name David Frandtsøn. He, like their marriage, was born of the trade.4

* * *

In the first generation of cassare marriage in Osu, Ga women and Danish men were much more foreign to each other than Severine and Edward were a century and a half later. Both Koko’s parents were African, and it is highly unlikely that she wore European clothes, or owned European goods and furniture. Both Koko and Frantz came from families of traders; Frantz had grown up in Copenhagen (København, meaning “merchants’ harbor”), which had been a trading center since the Middle Ages. They even had a culture of smoked and salted fish in common. Yet to recognize their similarities, they would both have to look beyond vast cultural differences. At least one of them had to adjust to the other’s culture, and since they were in Osu and since Europeans were fully dependent on their African trading partners in the early eighteenth century, it was mostly Frantz who adjusted. Even more important, Danish men relied on African women not only to succeed in trade, but also—humblingly and immediately—to survive.

The cassare marriages largely happened on initiative of the Ga, who were interested in and accustomed to integrating “foreign” African (primarily Akan) and European traders into their kinship groups. They made trading and political connections with Europeans by marrying their daughters to them, and both the gendered settlement patterns and division of labor in the Ga community, as well as the practice of adopting children of absent or deceased fathers, made the integration of foreign men easy. The men at Christiansborg, in turn, depended on relationships with an African kinship group: the process of overcoming cultural displacement when settling in Africa was not going to happen at the fort, but in Osu; and having a steady relationship with a Ga woman was crucially important in this process. Finally, the cassare marriages have an important story to tell about the familial, generational production of racial difference in the slave trade, which we will turn to in the last section of the chapter.

Osu, like Christiansborg on the beach nearby, grew up with the trade. The village—or town, as it would soon become—was one of a number of Ga villages along a twenty-mile stretch of the eastern Gold Coast that had been settled in the seventeenth century, after the Ga kingdom of Ayawaso was conquered and destroyed by the Akwamu. Besides farming and fishing, the Ga, from the earliest years, made their living as intermediaries in trade between Europeans and politically powerful groups of Akan-speaking peoples further inland (such as the Asante, Akwamu, and Akyem). Until the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, gold was the major export from the Gold Coast; in the eighteenth century, the Atlantic slave trade became the most important by far. Ga and other coastal traders brought European commodities inland and exchanged them for enslaved people, whom they brought with them back to the coast to sell to Europeans.5

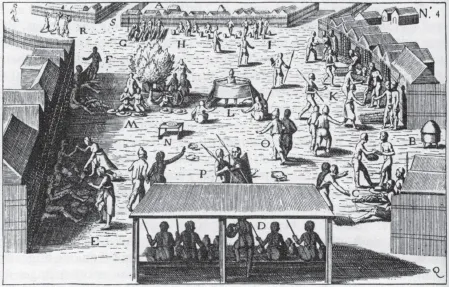

People on the Gold Coast had been trading with European men at least since the late fifteenth century, when Portuguese traders had begun tapping into an already well-developed commercial economy in West Africa from the sea (Figure 2). When the Danish West India and Guinea Company arrived in the seventeenth century, Dutch, English, French, and Swedish companies were already competing in the West African trade, and the later-arriving northern European traders adopted many practices and patterns from their Portuguese predecessors. Portuguese at first functioned as a fully developed lingua franca in the trade between Europeans and Africans, and the practice lived on for centuries in the shape of Portuguese loan words and phrases—including, most important for this study: cassare for marriage (from casar, meaning “to marry”); casse or kasse for “house” (from the Portuguese casa); caboceer for “head” or “chief” (from the Portuguese cabeceire); and neger for Africans (from the Portuguese negro, meaning “black”; this term was adopted by Danes and other Europeans as a term for Africans).

Figure 2. “The market at Cabo Corsso,” 1602. The population of Cape Coast grew from around one hundred inhabitants in 1555 to around three or four thousand in the early eighteenth century. The rest of the coast also saw a significant (though not quite as dramatic) increase in the urban-based, nonfarming population between 1550 and 1650. De Marees, Pieter, 62.

Trade between Europeans and Africans was intense on the Gold Coast. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sixty European forts and lodges were established along the coast, and the political situation and power balance in the coastal region changed constantly. However, European traders who arrived in West Africa always had to accommodate to the African societies they encountered. Europeans who built forts or lodges on the coast did so with permission from local African rulers, who required tribute as a prerequisite for good trading relations. As Portuguese and all other European traders in West Africa understood, trading on the coast required close connections to both inland rulers and the coastal middlemen they supplied.6

Danes had been involved in long-distance trading for centuries, at least since the early Middle Ages—the Viking age, as that period is still referred to in Denmark—and Danish merchants had been interested in trading with Africa since early in the seventeenth century. They adopted the Portuguese word Guinea to describe the area from the Gambia River to Congo, along with the Portuguese practice of describing areas of the coast after the primary products traded there: the Pepper Coast, the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast, and the Slave Coast. The first Danish company trading in West Africa was started in the 1650s, but the Danes did not gain a steady presence on the coast until the eighteenth century. The Danish administration on the Gold Coast was for the most part the responsibility of chartered Danish trading companies, regulated at the top level by charters (octroyer) issued by the Danish king. Responsibility for maintaining and manning the forts was a regular point of conflict over the centuries, though ultimately the king’s administration often took on the obligation.7

Fort Christiansborg was built by Swedes in 1652 and taken over by Dutch traders in 1660, then by the Danish West India and Guinea Company in 1661. From 1679 to 1683 the fort was briefly in the hands of the Portuguese after being sold to a merchant for thirty-six pounds of gold. In 1685 the fort became the Danish headquarters on the coast, and during the eighteenth century the fort was by far the biggest of the Danish trading forts on the Gold Coast. In the early years the fort consisted of about half a dozen living and storage rooms that could not be defended against any attacks, but it became more substantial as the Danish slave trade expanded during the eighteenth century. From a tiny and unstable beginning, the Danish trading companies managed to gain a fragile, unenforceable monopoly on the trade eastward from Osu, as far as Keta and through a chain of nine subordinate forts and lodges (see Map 3). Between 1660 and 1806 Danish ships brought about eighty-five thousand enslaved Africans across the Atlantic.8

A few miles west of Osu both the English and the Dutch had smaller forts; their own headquarters were farther off, in Cape Coast and Elmina, respectively. Each of these European trading posts in the Accra area developed trading relations with one or more of the local Ga towns. During the eighteenth century these settlements were known as Osu (Danish Accra), Soko (English Accra), and Aprag (Dutch Accra) (see Map 2).9 Since they were competitors in the slave trade, the nearby Europeans were both potential rivals and cultural peers for the Danes. During peacetime they paid social visits to the other forts, but they were often at odds with one another, which led to disagreements and sometimes even hostile confrontations. However, trade required successful dealings with African slave traders more than with other Europeans, and the cassare marriages became central to those trading alliances.10

The first key to understanding the context of the cassare marriages is that Danish and other European men had almost no direct support from European colonial or trading institutions in the early decades on the Gold Coast. Their forts in Africa were built with permission from African rulers, and they survived on the mercy of their African trading partners. Indeed, during the slave trade it was a common saying among Europeans on the Gold Coast that heaven was high and Europe far away. Late in the eighteenth century, Danish surgeon and travel writer Paul Isert used the expression to comment on the style of government at Christiansborg, where the governor was so far from his superior authorities that he could rule the trading post as a despot without fear of any retaliatory measures. Another Dane, chaplain H. C. Monrad, believed the saying suggested that it was easy to cheat and to trade in illegal and inhumane ways when trading so far away from home.11 The saying echoes a feeling many European men must have had on the Gold Coast, that both familiar authorities and familiar ways had little relevance to their daily lives.

In the seventeenth century, the Danes’ position on the Gold Coast had been even more precarious. In 1672, fifteen years after the Danes had first settled on the Gold Coast at the small fort of Frederiksborg, it was indeed difficult for the Danes to maintain contact with heaven, Europe, or any other superior authority. There were only eight Danish men left at Frederiksborg and three at Christiansborg when Governor von Groenestein described the situation in a letter to the Danish king Christian V: “Our situation here worsens day by day; and will worsen all the more if the Company cannot be got to send men here for the coming spring of 1673; for then we and HRM’s [his Royal Majesty’s] stations will be in great peril of being lost…. We cannot live here with empty hands under a barbaric nation that keeps neither faith nor promises; nor are we able, in an open station, to defend ourselves against them.”12 The governor continued that the Dutch and the English would be of no help if the Danes were attacked, since they would “like nothing better than to see us dispossessed.”13

When Governor Prange arrived on the coast in 1681, the Danish establishments in Africa teetered on the edge of failure. Christiansborg had been sold, and Frederiksborg, following a series of deaths, had fallen under the control of first one and then another self-appointed “interim governor,” who reportedly squandered all the company’s wealth on “whores and other frivolities.”14 The only Danish subjects remaining at the fort were two young Norwegians, one of whom offered an account of what had happened. After Governor Crull died, assistant Mathias Hansen had taken control of the fort with support from “the Negroes,” to whom he had given so many gifts that they would “make him” general.15 Hansen lasted five weeks as governor until another assistant, Pieter Valck, convinced “the Blacks” to shift their allegiance to him, and with the help of a hundred men he overwhelmed the fort. Pieter Valck thereafter sent Mathias Hansen to the Dutch at Elmina and ruled Frederiksborg in a “bestial” manner for four months until “we whites” (the two surviving Norwegians) asked the king of Fetu for help. The king then sent his men to the fort to seize Pieter Valck. According to Andreas Jacobsen, the king of Fetu at this point suggested that Jacobsen become general: “The King came into the fort and asked if I now wished to be general; otherwise he would appoint his son.”16

Pieter Valck was still in Fetu when the new governor Magnus Prange arrived from Copenhagen, but it is unclear whether he was there as a captive or was staying voluntarily. In an undated and rather confused letter from Fetu, Valck wrote to Frederiksborg requesting to be allowed to stay with “the heathen” but nevertheless added that he would like to come to the coast if only he had the opportunity, though he knew he would be arrested. He claimed that his reason for writing was to request that clothes be sent to Fetu, since he had no more than “a torn shirt and trousers” left, but he went on to ask for ink and paper, a small pot of brandy, and a little tobacco. Whatever Pieter Valck was doing in Fetu, it is interesting to note that the king of Fetu not only could decide who was going to be in charge at the Danish fort, but also had a say in how long they stayed in power.17

While assistant Pieter Valck was in Fetu, Governor Prange died. This left Frederiksborg in the hands of the German Johan Conrad Busch, who had started his career on the Gold Coast in 1673 as a cadet in the Dutch West Indian Company at Elmina. Hans Lykke, who was soon to become interim governor, reported to the West India and Guinea Company that Busch had been constantly drunk for eight days, had shot off about eight hundred pounds of powder for no reason, had given the company’s best pantje18 and gold away to whores and strangers, and had threatened to kill whoever approached him. Not only was the situation bad for the employees at the fort, but the king of Fetu was also upset about the governor’s behavior and threatened to stop supplying the Danes with the millet19 and water they needed to survive. Hans Lykke ascribed some of Busch’s misbehavior to his marriage to “a young Mulatto woman from de Min...