![]()

CHAPTER 1

Secondhand Repertory: The Fall and Rise of Master W. Shakespeare

He was an actor. He was other people.

—Michael Martone, “Everybody Watching

and the Time Passing Like That”

Beginning with Errors

William Shakespeare’s name appears for the first time in any theatrical record on March 15, 1595. Shakespeare scholarship typically asserts that this record is in error.

Shakespeare’s name had previously appeared on his poem Venus and Adonis in 1593 and on The Rape of Lucrece in 1594, and a pamphlet in 1592 had glanced at a player who had taken to “bombast[ing] out a blanke verse” and considered himself “the onely Shake-scene in a countrey.”1 That pamphlet links the versifying “upstart Crow” to a line from the play known either as The True Tragedy of Richard, Duke of York or as The Third Part of Henry the Sixt, jeering at a “Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde,” but no version of that play would be attributed to Shakespeare explicitly for another quarter-century, and the allusion in the compounded “Shake-scene” only becomes unambiguously convincing after one is already convinced that William Shakespeare was a player, a dramatist, and the author of The Third Part of Henry VI. That “Shake-scene” is the identifying word, rather than “Iohannes” or even “Crow,” is only clear once it has become clear. Had William Shakespeare left London in 1594 and been mentioned in no further records, there would be no conclusive way to link the upstart player attacked in the pamphlet to the fashionable erotic and narrative poet. Shakespeare was not mentioned as writer of a plays until 1598. Until 1595, there is nothing to confirm that Shakespeare was involved in the theater at all.

On March 15 of that year, a warrant for £20 from the Chamber accounts is made out “To Willm Kempe Willm Shakespeare & Richarde Burbage seruantes to the Lord Chambleyne . . . for twoe seuerall comedies or Enterludes shewed by them before her Matie in xpmas tyme laste paste . . .”2 specifically on St. Stephen’s Day (December 26) and Innocents’ Day (December 28). Shakespeare appears for the first time accompanying the partners and associates with whom he would spend the rest of his career, and who would define that career even after his retirement and death: the Lord Chamberlain’s Servants. Shakespeare was apparently already a prominent member, joined in delegation with the company’s leading man, Burbage, and their star clown, Kemp. (The chief performers only appear as payees this one time, after the company’s first Christmas at court.) Since the document in March deals with performances from the previous December, scholars have taken it to confirm his company membership by the time of those Christmas performances; since the Chamberlain’s Men originally formed sometime during the first half of 1594, theater history has generally presumed Shakespeare’s presence at the company’s founding. This warrant is thereby used in the way Elizabethan theatrical documents are often, indeed as they are typically used: to reconstruct a narrative about an earlier, undocumented period in Shakespeare’s career. Shakespeare is being given priority, in every sense of that word. The evidence is valued to the extent that it can be used to create a coherent biographical narrative about William Shakespeare, even if scholars must preserve that narrative coherence by emending the evidence and labeling it as mistaken.

Although the warrant explicitly refers to “Innocentes daye,” meaning December 28, 1594, this detail is pronounced erroneous by standard histories and reference works because it conflicts with another document, a record that mentions neither Shakespeare nor the Chamberlain’s Servants by name. The Gesta Grayorum, an account of student entertainments at Gray’s Inn, reports that “a Comedy of Errors (like to Plautus his Menechmus) was played by the Players” to conclude the celebrations “upon Innocents-Day at Night” in 1594.3 The “Players” themselves are not identified. But since The Comedy of Errors is alluded to by plot and title, the players have been presumed to be the Chamberlain’s Men. Two performances on Innocents’ Day by the same company has struck many theater historians as impossible; to resolve the difficulty, the wording of the court warrant is often disregarded and the date it gives replaced with a speculative date, in order to keep Shakespeare, his company, and his plays imaginatively inseparable.4 If someone gave The Comedy of Errors on the night of December 28, the implied logic goes, then it must have been Shakespeare and his partners, even if they were somewhere else.

Moreover, the plays are imagined as inseparable from their author from the outset, taking what was Shakespeare’s as forever and uninterruptedly his. That the Chamberlain’s Men were only months old, that Shakespeare’s previous company membership is practically impossible to establish, and that the date of The Comedy of Errors’s composition is unknown makes no difference to the scholarly debate over who might have performed the comedy in December, 1594. Almost no such scholarly debate exists.5 Shakespeare’s possession, and by extension that of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, is taken as self-evidently secure, secure enough to adjust the date on an apparently contradictory piece of evidence, and questions of date and provenance work backward from the security of this principle. Even if the conclusion itself is plausible, the methodology is unsettling. A serious case can be made that the Chamberlain’s Men performed The Comedy of Errors on the night in question, but no one has bothered to make it. The conclusion is not defended or advanced but treated as an initial premise. The explicit documentary record of Shakespeare’s life in the theater begins with a record that Shakespeareans refuse to accept at face value, and this refusal is presented as common sense.

This evidentiary sunspot may seem a small matter compared to the larger questions of Shakespeare’s canon and Shakespeare’s biography. And it may seem superficially logical to consider a single anomaly within the context of a broad, established pattern of theatrical ownership. But in the case of the Chamberlain’s Men’s initial repertory, virtually all of the evidence is anomalous, and the pattern is a scholarly construction. The general rules do not hold true in any of the specific cases. The presumption of the company’s claim to The Comedy of Errors might be strengthened by its demonstrated claim to a number of other Shakespeare plays in 1594, but their claims to each of those plays, at least in their canonical Shakespearean forms, is murkier than their claim to Errors, and none of their claims are demonstrable. Any claims about which plays the Chamberlain’s Men owned in 1594, or about what the 1594 texts of those plays were like, demands intense interpretation of ambiguous and fragmentary evidence. The Comedy of Errors, documented as being played on the same night the Chamberlain’s Men are documented playing somewhere else, is actually the play to which they have the least ambiguous claim.

Scholars necessarily reconstruct the beginning of the company’s history from later testimony. But Shakespeare’s partners and fellows in the Chamberlain’s Men, the most important witnesses to his career and the providers of most of that later testimony, had deep professional investments in the public perception of Shakespeare and of his canon. The claims of the playing company’s leaders constitute the most valuable source for recreating the company’s history, but they are not a neutral source. The Chamberlain’s Servants, who became the King’s Servants after the accession of James I, would go on to become the most powerful and durable acting company in early modern English history, maintaining their theatrical preeminence until the playhouses were closed in 1642. Shakespeare’s partners in art and business alike, they became the custodians of his reputation and arbiters of his dramatic canon after his death, most importantly by overseeing the folio publication of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in 1623, the famous First Folio. The King’s Men are the closest thing to an authorized biographer that Shakespeare has ever had. But their account of him is naturally colored by their hindsight and by their success. The beginnings of Shakespeare’s theatrical life are seen through the lens of his later career; early evidence about him is tested for consistency with the familiar, established figure of William Shakespeare the King’s Man, and with the King’s Men’s narratives about that figure. The formation of the Chamberlain’s Men in 1594 is Shakespeare’s defining moment; it has come to define everything he did afterward, and everything he did before. Shakespeare scholars, themselves deeply committed to the Shakespeare of the Globe and the Blackfriars, are unsurprisingly comfortable with the tacit teleology that makes young Shakespeare into an image of the mature Shakespeare, and the 1623 Folio into the alpha and omega of his working life.

But the company in 1594 was many years from the dominant position it would later achieve. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men formed during major upheavals in London’s theater business and faced powerful and competitive rivals. The first years of their partnership were spent consolidating their position; in subsequent years they were committed to the public identity they formed in those years, and to the narratives that supported that identity. The star of the story that the Lord Chamberlain’s Men devised for themselves, and adapted to their professional needs, was their colleague William Shakespeare.

Two Households: The Events of 1594

In 1594 the Privy Council reopened London to professional actors after two years of nearly continuous prohibition. The Council had restrained playing in the capital late in June 1592 after some rioting by apprentices,6 and high death tolls from the plague had subsequently kept the London playhouses closed, with only occasional brief intermissions, until spring 1594. In the meantime, one major playing company fell on hard times; a letter by the playhouse owner Philip Henslowe describes Pembroke’s Men “breaking” while in the country, unable to defray their costs, and returning to London in August or September 1593. The professional English playing companies had been designed for touring, as Scott H. McMillin and Sally-Beth McLean point out,7 but as Mc-Millin and MacLean also demonstrate, the high profits of playing London had led the professional companies first to commission and then to depend upon plays requiring larger casts,8 so that the economics of urban playing circa 1592 might have proved unsustainable in the provinces. Lord Strange’s Men had made precisely this argument when petitioning the Privy Council to lift the restraint: “our Companie is greate, and thearbie our chardge intollerable, in travellinge the Countrie, and the Contynuance thereof wilbe a meane to bringe us to division and separacion.”9 This claim was rhetorically motivated, to be sure, and claims made during clients’ appeals to patrons should not be taken too literally. The Strange’s Men subsequently managed to travel the country for two years without bankruptcy, and dividing a company into smaller touring units seems to have been a well-known practice.10 But at least some actors believed that the economics of touring with a large company would lead to the dissolution of companies, as was the case for Pembroke’s Men. And every major playing company from the era would undergo significant changes (of personnel, of patron, of court privileges) during the long restraint and its aftermath.

The Privy Council did not merely reopen the London playhouses but chose two groups of players as favorites to be promoted. The Lord Admiral, Charles Howard, and Henry Carey, the Lord Chamberlain, allies and kinsmen by marriage, each took direct charge of a company as official patron. Beginning with the Christmas season of 1594, the Admiral’s Men and the Chamberlain’s Men shared a monopoly on Court performances. While this might seem to be personal favoritism by Lord Chamberlain Carey, Andrew Gurr points out that neither Howard nor Carey had previously given any such advantage to acting companies they had patronized.11 The restriction of Court performance to two companies was rather favoritism as an official tool of policy. Two companies were to share the privilege of performing for the Queen. The two Privy Councilors’ companies would also be given exclusive privileges to perform in London and its suburbs. A Privy Council minute from February 1598 makes that exclusivity official.12 Gurr proposes that the Council’s policy, privileging what he calls the “duopoly” of two companies, was actually instituted in 1594.13 Whether the shared monopoly began in 1594 or later, the Admiral’s and Chamberlain’s companies were clearly the leading London companies, and the Court’s favorites, from that spring onward. The companies that had dominated the Christmas revels in the preceding years, such as the Queen’s Men, the Earl of Pembroke’s Men, and the Earl of Sussex’s Men, disappear from the Court records entirely after Twelfth Night 1594.

Some of the players from those earlier groups may have joined the newly favored companies, some might have simply changed their names and patrons, and the companies that left London to tour England were not failures on their own terms. The ongoing Records of Early English Drama (REED) Project, which has undertaken the first complete compilation of early English performance records, continues to demonstrate how misleading theater historians’ “London bias” has been. The Queen’s Men, especially, had a long and honored provincial career even after they lost the privilege of performing before the Queen.14 But while the touring performers would go on to play an important role in the history of English theater, 1594 marks their exit from the history of English professional drama and its development. They could continue playing and even thriving without access to London. But it was London’s unique resources, its enormous and lucrative market for plays, its supply of professional writers, its proximity to Court and access to the book trades,15 combined with London’s unique business pressures, its voracious audiences and close competition, that drove the literary evolution of the drama.

A touring company needed fewer plays in its repertory than a London company offered in a given week, and the playhouses relied on customers returning for more than one weekly show. Pleasing such customers required material that could satisfy the same viewers repeatedly, in enough supply that they not be served the same meal too often. The extant corpus of English professional drama was written for those playhouse audiences. The artistic richness of the surviving plays stems from that audience’s extraordinary demands and from the competitive pressure that the London companies exerted upon one another. Neither company could afford to fall behind the other in artistic sophistication; both worked to outdo the other, and their audiences grew accustomed to increasingly better-crafted plays. The rapid flowering of English drama as an art form comes from the hothouse of London.

The leading players in the Admiral’s Men and the Chamberlain’s Men were collegial competitors, or at the very least had been colleagues before becoming rivals. Five of the leading partners in the original Lord Chamberlain’s Men had been performing with Edward Alleyn, the leader and star of the Lord Admiral’s Men, throughout the restraint on playing in London. A traveling license from May 1593 lists the sharers of their company as “Edward Alleyn servant to the right honorable the lord high Admiral, William Kemp, Thomas Pope, John Heminges, Augustine Phillips and George Brian, being of one company, servants to our very good lord the Lord Strange.”16 Many scholars have described this group as the “amalgamated” Strange’s and Admiral’s company, but the group is better described as Lord Strange’s Men and the Admiral’s Man; even though Alleyn had joined the Lord Strange’s Men as an actor, he evidently refused to subordinate his personal relationship with his patron to the group’s collective identity. Alleyn’s stubbornly egotistic fidelity was vindicated when the playhouses were reopened and he once again led a full company of Admiral’s Men, stronger than they had ever been.

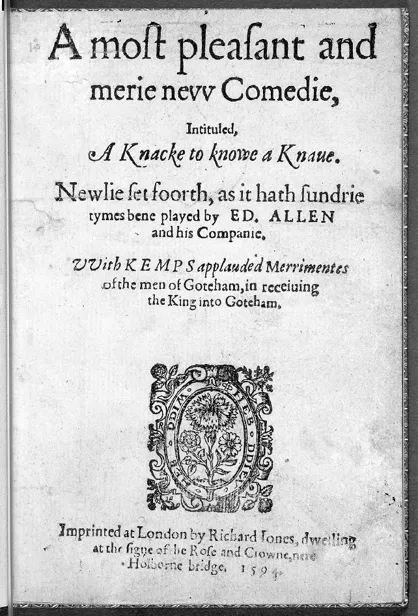

Figure 1. Title...