![]()

CHAPTER ONE

__________

A Free People, Subject to No One

In 1643, the New Sweden governor Johan Printz believed that it would be extremely difficult to convert the Lenapes to Christianity: “when we speak to them about God they pay no attention, but they will let it be understood that they are a free people, subject to no one.” He made an accurate assessment, for the Native people of Lenape country resisted Christianization through the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Their insistence on autonomy extended to areas beyond religion as well—to government, ownership of land, and individual rights. Though population decline resulted in some merging of communities, the Lenapes avoided forming an overarching government, instead keeping their decentralized organization of affiliated towns. And despite the claims of the Iroquois and some historians, the Five Nations (after 1722, the Six Nations) held no suzerainty over the Lenapes until the 1730s, and even then the Iroquois controlled only the minority who had moved to their territory. Similarly, some historians, using scanty evidence, have argued that the Susquehannocks dominated the Lenapes during the seventeenth century, while in fact their war of the late 1620s and early 1630s ended with confirmation of Lenape sovereignty over their land and a close alliance between the two peoples. The Lenapes also remained committed to personal freedom—for individuals within their communities, for other Natives, and for the newcomers who arrived from Europe. While defending their territory, the Lenapes welcomed trade with the Dutch, Swedes, and English, granting them enough real estate to conduct business. Unlike Natives such as the Chickasaws and Creeks in the American Southeast and the Iroquois, the Lenapes did not fight wars to enslave people or forcibly adopt strangers into their families.1

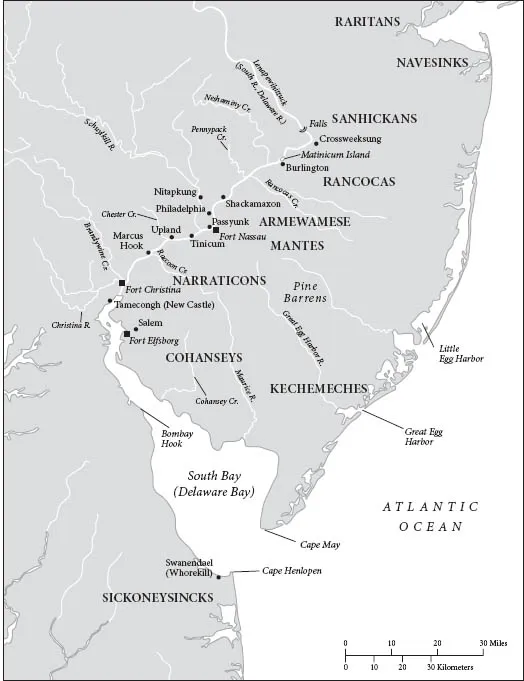

The Lenapes built their towns along streams in the coastal plain, stretching from what is now central and southern New Jersey through eastern Pennsylvania to northern and eastern Delaware (see Map 2). The soils on both sides of the Lenapewihittuck were good to excellent for agriculture, while tidal marshes and sandy beaches characterized the banks of Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The New Jersey Pine Barrens of pines, cedar, oaks, and sandy soil comprised a large area adjacent to the bay and sea.2 The Lenapes cultivated corn (maize) and other crops in arable fields near their towns; hunted for deer, bear, beaver, and other animals in the larger region; gathered wood and berries in the Pine Barrens; and caught fish in creeks and rivers, and shellfish at the shore. They produced pottery, clothing, stone weapons and tools, and they practiced basket making and other crafts. Though the Lenapes engaged in long-distance trade with other peoples of eastern North America, they remained outside the mound-building, hierarchical civilizations that flourished prior to European contact in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys.3 The Lenapes’ sociopolitical structure was democratic and egalitarian, as the sachems held authority only by consulting with a council of elders and following the expectations of their people. Each town claimed ownership to specific territory, which the town as a whole, represented by the sachem, could sell (or refuse to sell) without obtaining approval from other Lenape communities, the Susquehannocks, or Iroquois.

Our knowledge of Lenape country in the early seventeenth century is based largely on the reports of Dutch explorers and traders who entered the Lenapewihittuck (which the Dutch called South River) in about 1615. The Dutch explorer Cornelis Hendricksen in 1616 published the first extant European map of the region, indicating two Lenape groups on the river: the “Stankekans” (Sanhickans) and “Sauwanews.” He situated the Sanhickans on both sides of the Lenapewihittuck and the Sauwanews on the east bank. On later maps the Sanhickans are shown in various parts of central New Jersey, from present-day Trenton toward Manhattan, and the Sauwanews appear on the west bank near the Schuylkill River. In the 1630s, European maps and documents show Lenape towns on major streams feeding into the Lenapewihittuck, identifying the Sickoneysincks, Kechemeches, Cohanseys, Sewapois, Asomocches, Narraticons, Mantes, Armewamese, Rancocas, Atsayans, Sanhickans, and others.4 Because the Susquehannocks burned Lenape towns and drove the inhabitants to the east bank of the Lenapewihittuck in the late 1620s and early 1630s, some of the first evidence from Europeans depicts the Lenape population in flight. Even after the Susquehannocks and Lenapes declared peace by 1638—and Lenapes built new towns along the west bank—epidemics of European diseases created further dislocation as former neighboring communities merged.5 The early information is approximate because European mapmakers often either based their drawings on sketchy narratives or simply copied out-of-date evidence from previous maps. Intermittent contact between Europeans and the Lenapes, their seasonal movement, and war with the Susquehannocks in the 1620s and 1630s account for these variations among early European maps. Even so, the combination of archaeological remains, maps, and records suggests that a substantial Lenape population living in autonomous towns throughout the region survived the Susquehannock war and Dutch contact.

By the mid-seventeenth century, some Lenape communities, such as the Sickoneysincks at Cape Henlopen, continued to live in approximately the same locations, while others had relocated from New Jersey to the west bank. A Swedish engineer, Peter Lindeström, surveyed and mapped the river in 1654, providing brief descriptions of Native towns and assessing the land for economic development. He started at Cape Henlopen, where he noted that the Sickoneysincks were “a powerful nation and rich in maize plantations.” He then traveled along the east bank, mentioning ways in which the Lenapes used the land and various plants, but he did not report any towns until his vessel reached the Falls near Assunpinck Creek, where “there is along the river a beautiful and good land, suitable for black and blue maize, Swedish barley and other such like. [It] is a level and good land for pasture, where the savages have lived for a long time, and are still dwelling.” Lindeström wrote that the Mantes people now lived at the Falls and northward on the river where only canoes could travel. The Mantes, he explained, “which nation is the rightful owner of the east side of the river” that was “formerly mostly occupied” by them, “yet this nation is now much died off and diminished through war and also through diseases.” Lindeström also noted that the region was “very rich in all kinds of wild animals and birds, and in the river as well as in the kills and streams emptying into it, there is an abundance of fish of various kinds.” When the Mantes people ran short of grain, they moved to the west bank where they hunted and fished, selling their surplus to the Swedes and other Natives.6

Lindeström considered Chiepissing, which he located on the west bank, south of the Falls, particularly good land for pastures and for growing corn, and “for many years has been occupied and cultivated.” At midcentury, the majority of Lenapes on the west bank lived near the Schuylkill, which Lindeström praised for its beauty, freshwater springs, many fruit trees, and “abundance of various kinds of rare, wild animals, which, however, now begin to become somewhat diminished” from the Lenapes’ hunting. Lindeström esteemed the region highly, identifying six Lenape towns from Wicaco to the falls of the Schuylkill at Nittabakonck. “This is occupied in greatest force by the most intelligent” of several Lenape groups “who own this River and dwell here. There they have their dwellings side by side one another” and have “cleared and cultivated [their land] with great power.” Six sachems led these Lenape settlements, there “being several hundred men strong, under each chief, counting women and children, some being stronger, some weaker.” Lindeström wrote that four communities—Poaetquessingh, Pemickpacka, Wickquaquenscke, and Wickquakonick—were located along the Lenapewihittuck, while Passyunk and Nittabakonck lay by the Schuylkill. This district, he noted, “they rightfully own.” These were Armewamese and other Lenape people led by Mattahorn, Ackehorn, Sinquees, and other sachems, who built towns in this region to take advantage of the fur trade with the Susquehannocks, Dutch, and Swedes, for which the Schuylkill River was a terminus. As Lindeström noted, they also grew corn on a large scale, selling it as a cash crop to the Swedes who frequently fell short of food.7

The remainder of Lindeström’s tour passed the Swedish, Finnish, and Dutch settlements south from the Schuylkill River. He noted it was “a level, very splendid and fertile land, good and suitable for whatever we may desire to plant, as everything grows there abundantly.” He marveled, “Yes [it is] such a fertile country that the pen is too weak to describe, praise and extol it [sufficiently]; yes indeed, on account of its fertility it may well be called a land flowing with milk and honey.” The region farther south toward Cape Henlopen was fertile but uninhabited by colonists or Natives.8 These remained, for the most part, Lenape hunting lands.

Lindeström provided no report on the Lenape communities that were situated on the east bank along Rancocas, Timber, Raccoon, and Cohansey creeks; Maurice River; or near the Atlantic shore at Barnegat, Little Egg Harbor, and Great Egg Harbor. New Netherland Secretary Cornelis van Tienhoven wrote in 1650 that “large numbers of all sorts of tribes” passed through central New Jersey “on their way north or east.” Augustine Herrman, who purchased land on the Raritan River and knew the region well, indicated Lenape towns in southern and central New Jersey on his 1670 map. He labeled the area between Sandy Hook and the Lenapewihittuck as “at present inhabited only or most by Indians.” Lenapes had kinship ties and frequent contact with Munsees close to Manhattan—particularly the Raritans, who lived on Staten Island and the adjacent region north of the Raritan River, and the Navesinks, who controlled the region from the Raritan River south and east to Barnegat Bay.9

Calculations of the Lenape population range widely for the early seventeenth century, with variations resulting from the impact of disease and war and from the lack of documentation such as censuses of Native Americans. Most scholars provide early figures of 8,000 to 12,000 for the Munsees and Lenapes combined; these numbers, as the scholar Herbert Kraft has noted, likely undercount the precontact population because Natives succumbed to diseases brought by sailors and fishermen even before the Dutch arrived. For the Lenapes alone in 1600, Ives Goddard estimated 6,500, which is probably low. An Englishman, Robert Evelyn, who traveled in 1634 to the Lenapewihittuck with his uncle, Captain Thomas Yong, provided data on the size of eight Lenape groups on the east bank from Cape May to the Falls. He counted 940 men available to defend the Kechemeches, Mantes, Asomocches, Armewamese, Rancocas, Atsayans, Calcefar, and Mosilian communities. If one assumes an average family size of four to five people, the population of all these groups was 3,700 to 4,700.10 In his account, Evelyn omitted the Sickoneysincks at Cape Henlopen; the Cohanseys, Narraticons, and Sanhickans in New Jersey; and the Lenapes on the west bank in what is now Pennsylvania and northern Delaware, of whom some relocated to New Jersey because of the Susquehannock war. Evelyn thus included about one-half of the Lenapes in his report, bringing their number in 1634 to about 7,500 to 9,000.

Although they apparently did not suffer as severely as some other groups, the Lenape people decreased in population between the 1630s and 1650s, with epidemics of smallpox and other diseases brought by the Swedes and other Europeans. Throughout North America, French, Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers carried the deadly microbes of smallpox, influenza, measles, and other viruses for which Native Americans lacked immunity. Susquehannocks, on their regular visits to the Lenapewihittuck, carried contagion from their trading partners, the Hurons, who had endured waves of epidemics in the 1630s. As early as 1633, smallpox struck the Mohawks, who traded with the Dutch; the Senecas and other Iroquois endured epidemics by 1641. Disease destroyed at least one-half of the Huron and Iroquois populations by the 1640s, with continued plagues in following years decreasing their numbers before European contact by 90 to 95 percent. Cornelis van Tienhoven believed in 1650 that Native populations had declined significantly on Long Island, as “[t]here were formerly in and about this bay, great numbers of Indian Plantations, which now lie waste and vacant.” Six years later Adriaen van der Donck, a New Netherland resident, wrote that Hudson Valley Natives reported “that before the arrival of the Christians, and before the small pox broke out amongst them, they were ten times as numerous as they now are.”11

Lindeström’s note in 1654 that several hundred men served under each chief sachem of the six towns near the Schuylkill is ambiguous because he could have meant that a total of 1,200 men lived in that area of the west bank, for a total population of perhaps 5,000 people, or that the total population, including women and children, was about 1,200. Whichever number is correct, with the addition of the Sickoneysincks at Cape Henlopen and other communities located in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the Lenape population totaled at least 4,000 at midcentury. Forty years later the Swedish ministers Andreas Rudman and Ericus Björk reported that the numbers of Lenapes living on the Schuylkill had dropped significantly since 1650. Peter Kalm, writing in the mid-eighteenth century, also learned that the Lenapes “previously lived quite densely, where Philadelphia now stands, and moreover lived everywhere in the country; but they became extinct through the measles, which they got from the Europeans, when many 100s died.”12

In 1650, despite the population decrease and trade with Europeans, the Lenapes held control of the region, retaining their autonomy and traditional ways of life while selectively adopting new technology from the Dutch and Swedes. Though women and men incorporated European goods into their daily lives, appreciating the convenience of woolen cloth, firearms, and metal tools, they adhered to their customary economic cycle of hunting, agriculture, fishing, and gathering. In late autumn, men organized the hunt, burning off undergrowth and creating fire-surrounds to trap deer and other game such as bears, wolves, and raccoons. Hunting parties could number more than one hundred people. In the winter, families lived in dispersed villages; with the arrival of spring, women planted corn, tobacco, beans, squash, and gourds. In summer and early autumn, Lenapes hunted; fished; tended and harvested the crops; gathered shellfish, berries, and wood; and dried fish and preserved corn for the winter. They commemorated the harvest with the green corn ceremony, their principal religious celebration, by dancing, singing, and feasting on corn and venison.13

Like other Natives of eastern North America, the Lenapes divided work on the basis of gender. Women raised the crops, gathered nuts and fruit, built houses, made clothing and furniture, took care of the children, and prepared meals. Men cleared land, hunted, fished, and protected the town from enemies. Europeans often criticized this division of labor because it differed from agricultural societies in which men took primary responsibility for planting and harvesting crops. Van der Donck wrote, for example, that the “men are generally lazy, and do nothing until they become old and unesteemed, when they make spoons, wooden bowls, bags, nets and other similar articles; beyond this the men do nothing except fish, hunt and go to war. The women are compelled to do the rest of the work, such as planting corn, cutting and drawing fire-wood, cooking, taking care of the children and whatever else there is to be done.” David de Vries agreed that “the women are compelled to work like asses, and when they travel, to carry the baggage on their backs, together with their infants, if they have any, bound to a board.” The Dutch scholar Nicolaes van Wassenaer, a compiler of newsworthy information from New Netherland in his Historisch Verhael, noted more favorably that North American women took responsibility for planting and gathering food. They prepared meals, including corn, which “is pounded …, made into meal, and baked into cakes in the ashes, after the olden fashion, and used for food.” Van Wassenaer observed that Native women followed the moon in making preparations for planting and harvest: they “are the most skilful star-gazers [who] … can name all the stars; their rising, setting.”14

Dutch and Swedish writers who commented on the Natives’ politics and society found the ...