![]()

PART I

Economics and Infrastructures of Energy Exporters

![]()

1

The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey

Jeffrey Frankel

It is striking how often countries with oil or other natural resource wealth have failed to show better economic performance than those without. This is the phenomenon known as the “natural resource curse.” The pattern has been borne out in econometric tests across a comprehensive sample of countries. This paper considers seven aspects of commodity wealth, each of which is of interest in its own right but also a channel that some have suggested could lead to substandard economic performance. They are: long-term trends in world commodity prices, volatility, permanent crowding out of manufacturing, weak institutions, unsustainability, war, and cyclical Dutch disease.

Skeptics have questioned the natural resource curse. They point to examples of commodity-exporting countries that have done well and argue that resource exports and booms are not exogenous. Clearly, the relevant policy question for a country with natural resources is how to make the best of them. The paper concludes with a consideration of ideas for institutions that could help a country that is endowed with commodities overcome the pitfalls of the curse and achieve good economic performance. The most promising ideas include indexation of contracts, hedging of export proceeds, denomination of debt in terms of the export commodity, Chile-style fiscal rules, a monetary target that emphasizes product prices, transparent commodity funds, and lump-sum distribution.

The Resource Curse: An Introduction

It has been observed for decades that the possession of oil or other valuable mineral deposits or natural resources does not necessarily confer economic success. Many African countries—such as Angola, Nigeria, Sudan, and the Congo—are rich in oil, diamonds, or minerals, yet their peoples continue to experience low per capita income and a low quality of life. Meanwhile, the East Asian economies of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong have achieved Western-level standards of living despite being rocky islands (or peninsulas) with virtually no exportable natural resources. Richard Auty is apparently the one who coined the phrase “natural resource curse” to describe this puzzling phenomenon.1 Its use spread rapidly.2

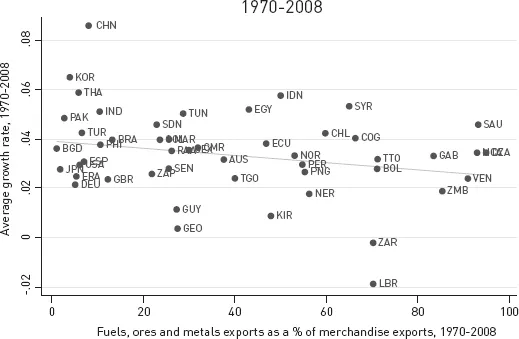

Figure 1.1 shows a sample of countries during the last four decades. Exports of fuels, ores, and metals as a fraction of total merchandise exports appear on the horizontal axis, and economic growth is on the vertical axis. Conspicuously high in growth and low in natural resources are China (CHN), Korea (KOR), and some other Asian countries. Conspicuously high in natural resources and low in growth are Gabon (GAB), Venezuela (VEN), and Zambia (ZMB). The overall relationship on average is slightly negative. The negative correlation is not very strong, masking almost as many resource successes as failures. But it certainly does not suggest a positive correlation between natural resource wealth and economic growth.

How could abundance of hydrocarbon deposits—or other mineral or agricultural products—be a curse? What would be the mechanism for this counterintuitive relationship? Broadly speaking, there are at least seven lines of argument. First, prices of such commodities could be subject to secular decline on world markets. Second, the high volatility of world prices for energy and other mineral and agricultural commodities could be problematic. Third, natural resources could be dead-end sectors in the sense that they may crowd out manufacturing, which might be the sector to offer dynamic benefits and spillovers that are good for growth. (It does not sound implausible that “industrialization” could be the essence of economic development.) Fourth, countries in which physical command of mineral deposits by the government or by a hereditary elite automatically confers wealth on the holders may be less likely to develop the institutions, such as rule of law and decentralization of decision making, that are conducive to economic development. These resource-rich countries suffer in contrast to countries in which moderate taxation of a thriving market economy is the only way the government can finance itself. Fifth, natural resources may be depleted too rapidly and leave the country with little to show for them, especially when it is difficult to impose private property rights on the resources, as under frontier conditions. Sixth, countries that are endowed with natural resources could have a proclivity for armed conflict, which is inimical to economic growth. Seventh, swings in commodity prices could engender excessive macroeconomic instability via the real exchange rate and government spending. This chapter considers each of these topics.

Figure 1.1 Statistical relationship between mineral exports and growth. World Development Indicators, World Bank.

The conclusion will be that natural resource wealth does not necessarily lead to inferior economic or political development. Rather, it is best to view commodity abundance as a double-edged sword, with both benefits and dangers. It can be used for ill as easily as for good.3 The fact that resource wealth does not in itself confer good economic performance is a striking enough phenomenon without exaggerating the negative effects. The priority for any country should be on identifying ways to sidestep the pitfalls that have afflicted other commodity producers in the past and to find the path of success. The last section of this chapter explores some of the institutional innovations that can help countries avoid the natural resource curse and achieve natural resource blessings instead.

Long-Term Trends in World Commodity Prices

Determination of the Export Price on World Markets

Developing countries tend to be smaller economically than major industrialized countries and more likely to specialize in the export of basic commodities. As a result, they are more likely to fit the small open economy model: they can be regarded as price takers, not just for their import goods, but for their export goods as well. That is, the prices of their tradable goods are generally taken as given on world markets. The price-taking assumption requires three conditions: low monopoly power, low trade barriers, and intrinsic perfect sub-stitutability in the commodity between domestic and foreign producers—a condition usually met by primary products such as oil, and usually not met by manufactured goods and services. Literally speaking, not every barrel of oil is the same as every other and not all are traded in competitive markets. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia does not satisfy the first condition due to its large size in world oil markets.4 But the assumption that most oil producers are price takers holds relatively well.

To a first approximation, then, the local price of oil is equal to the dollar price of oil on world markets times the country's exchange rate. It follows, for example, that a currency devaluation should push up the price of oil quickly and in proportion (leaving aside preexisting contracts or export restrictions). An upward revaluation of the currency should push down the price of oil in proportion.

Throughout this chapter, we will assume that the domestic country must take the price of the export commodity as given, in terms of foreign currency. We begin by considering the hypothesis that the given world price entails a long-term secular decline. The subsequent section of the paper considers the volatility in the given world price.

The Hypothesis of a Downward Trend in Commodity Prices (Prebisch-Singer)

The hypothesis that the prices of mineral and agricultural products follow a downward trajectory in the long run, relative to the prices of manufactures and other products, is associated with Raul Prebisch and Hans Singer and what used to be called the “structuralist school.”5 The theoretical reasoning was that world demand for primary products is inelastic with respect to world income. That is, for every 1 percent increase in income, the demand for raw materials increases by less than 1 percent. Engel's Law is the (older) proposition that house holds spend a lower fraction of their income on food and other basic necessities as they get richer.

The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis, if true, would readily support the conclusion that specializing in natural resources is a bad deal. Mere “hewers of wood and drawers of water” (Deuteronomy 29:11) would remain forever poor if they did not industrialize. The policy implication that was drawn by Prebisch and the structuralists was that developing countries should discourage international trade with tariff and nontariff barriers to allow their domestic manufacturing sector to develop behind protective walls, rather than exploit their traditional comparative advantage in natural resources, as the classic theories of free trade would have it. This “import substitution industrialization” policy was adopted in most of Latin America and much of the rest of the developing world in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The trend reversed in subsequent decades, however.

Hypotheses of Upward Trends in Nonrenewable Resource Prices (Malthus and Hotelling)

There also exist persuasive theoretical arguments that we should expect prices of oil and other minerals to experience upward trends in the long run. The arguments begin with the assumption that we are talking about nonperishable, nonrenewable resources, that is, deposits in the earth's crust that are fixed in total supply and are gradually being depleted. (The argument does not apply as well to agricultural products.)

Let us add another assumption: whoever currently has claim to the resource, an oil company, for instance, can be confident that it will retain possession unless it sells to someone else, who then has equally safe property rights. This assumption excludes cases in which private oil companies fear that their contracts might be abrogated or their possessions nationalized.6 It also excludes cases in which warlords compete over physical possession of the resource. Under such exceptions, the current owner has a strong incentive to pump the oil or extract the minerals quickly, because it might never benefit from whatever is left in the ground. One explanation for the sharp rise in oil prices between 1973 and 1979, for example, is that private Western oil companies had anticipated the possibility that newly assertive developing countries would eventually nationalize the oil reserves within their borders and thus had kept prices lower by pumping oil more quickly during the preceding two decades than they would have done had they been confident that their claims would remain valid indefinitely.

HOTELLING AND THE INTEREST RATE

At the risk of some oversimplification, let us assume for now also that the fixed deposits of oil in the earth's crust are all sufficiently accessible and that the costs of exploration, development, and pumping are small compared to the value of the oil. Harold Hotelling deduced from these assumptions the important theoretical principle that the price of oil in the long run should rise at a rate equal to the interest rate.7

The logic is as follows: At every point in time, an owner of the oil—whether a private oil company or a state—chooses how much to pump and how much to leave in the ground. Whatever is pumped can be sold at today's price (this is the price-taker assumption) and the proceeds invested in bank deposits or U.S. Treasury bills, which earn the current interest rate. If the value of the oil in the ground is not expected to increase in the future or not expected to increase at a sufficiently rapid rate, then the owner has an incentive to extract more of it today so that it can earn interest on the proceeds. As oil companies worldwide react in this way, they drive down the price of oil today, below its perceived long-run level. When the current price is below its perceived long-run level, companies will expect that the price must rise in the future. Only when the expectation of future appreciation is sufficient to offset the interest rate will the oil market be in equilibrium. That is, only then will oil companies be close to indifferent between pumping at a faster rate and a slower rate.

To say that oil prices are expected to increase at the interest rate means that they should do so on average; it does not mean that there will not be price fluctuations above and below the trend. But the theory does imply that, averaging out short-term unexpected fluctuations, oil prices in the long term should rise at the interest rate.

If there are constant costs of extraction and storage, then the trend in oil prices will be lower than the interest rate, by the amount of those costs; if there is a constant convenience yield from holding inventories, then the trend in prices will be higher than the interest rate, by the amount of the yield.8

MALTHUSIANISM AND THE “PEAK OIL” HYPOTHESIS

The idea that natural resources are in fixed supply and that as a result their prices must rise in the long run as reserves begin to run low is much older than Hotelling. It goes back to Thomas Malthus and the genesis of fears of environmental scarcity (albeit without interest rates necessarily playing a role).9 Demand grows with population, and supply is fixed; what could be clearer in economics than the prediction that price will rise?10

The complication is that supply is not fixed. True, at any point in time there is a certain stock of oil reserves that have been discovered. But the historical pattern has long been that as the stock is depleted, new reserves are found. When the price goes up, it makes exploration and development profitable for deposits that are farther underground, underwater, or in other hard-to-reach locations. This is especially true as new technologies are developed for exploration and extraction.

During the two centuries since Malthus, or the seventy years since Hotelling, exploration and new technologies have increased the supply of oil and other natural resources at a pace that has roughly counteracted the increase in demand from growth in population and incomes.11

Just because supply has always increased in the past does not necessarily mean that it will always do so in the future. In 1956, oil engineer Marion King Hubbert predicted that the flow supply of oil within the United States would peak in the late 1960s and then start to decline permanently. The prediction was based on a model in which the fraction of the country's reserves that has been discovered rises through time, and data on the rates of discovery versus consumption are used to estimate the parameters in the model. Unlike myriad other pessimistic forecasts, this one came true on schedule and earned subsequent fame for its author.

The planet Earth is a much larger place than the United States, but it too is finite. A number of analysts have extrapolated Hubbert's words and modeling approach to claim that the same pattern will follow for extraction of the world's oil reserves. Specifically, some of them claim the 2000 to 2011 run-up in oil prices confirmed a predicted global “Hubbert's Peak.”12 It remains to be seen whether we are currently witnessing a peak in world oil production, notwithstanding that forecasts of such peaks have proven erroneous in the past.

Evidence

STATISTICAL TIME SERIES STUDIES

With strong theoretical arguments on both sides, one must say that the question whether the long-term trend in commodity prices is upward or downard is an empirical one. Although spe...