![]()

Chapter 1

Real Life and the Nightlife in San Francisco’s Latin Quarter

Strolling out of Chinatown, you walk into another kind of world . . . the Latin Quarter! A world of intriguing little bookstores, Bohemian restaurants and Spanish, Basque, Mexican and Italian shops.

—San Francisco tourism brochure, 19401

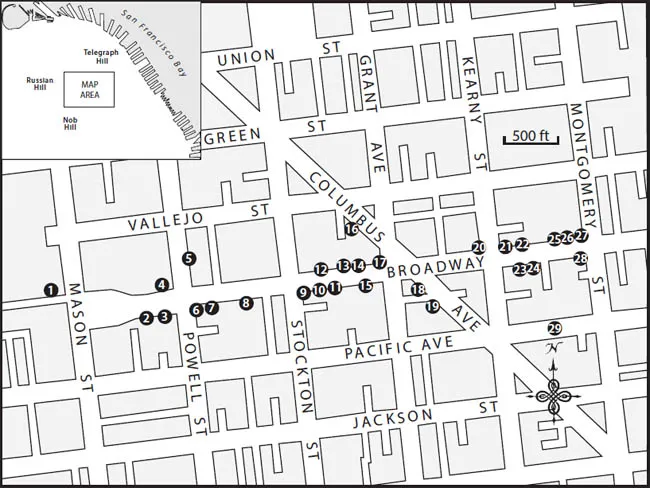

Prior to World War II, the Latin Quarter served as one of San Francisco’s larger Latino neighborhoods. Residents enjoyed Spanish mass at Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe church, access to two Spanish-language bookstores, and a variety of Latin American folk art stores, cafés, and restaurants that catered to those craving a taste of home, or to those seeking a foreign experience.2 The Teatro Verdi offered regular showings of Spanish-language films and advertised its location on Broadway, between Stockton and Grant, as “el Corazón del Barrio Latino” (The Heart of the Latino Barrio).3 Encompassing an area around Broadway and Powell Streets, the neighborhood is now seen as part of North Beach or Chinatown (Fig. 1.1). While the city still celebrates the history of neighboring Little Italy and historic Chinatown, few residents are familiar with the area’s Latino history.

In his 1940 guidebook, Leonard Austin reported, “Recent immigrants have settled in other parts of the city . . . but North Beach still remains the center of the Mexican population.”4 He described the vibrancy of the many Mexican shops and cantinas, but also pointed out smaller Mexicano or Latino neighborhoods on Fillmore Street, in the South of Market area, in the Mission, and in Butchertown, now known as Bayview. Latinos living in these earlier neighborhoods formed social networks and contributed to the cosmopolitan growth of the city. However, economic and social pressures drove many Latinos out of these neighborhoods and prompted some to move to the Mission District.5 These longtime city residents joined an influx of immigrants in the post–World War II period that contributed significantly to the Latinization of the Mission District. The change in physical location created a lack of continuity in the city’s Latino history.

Figure 1.1. Map of the Latin Quarter showing Latino social spaces, businesses, and other popular sites, 1930s–1960s. (1) Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe church, 1912–1991, 906 Broadway; (2) Spanish Cultural Center club rooms (Casino Pan America, 1940; La Marimba, 1941; Beige Room, 1951–1957; Copacabana, 1957–1967; Tropicoro, 1967), 831 Broadway; (3) Unión Española / Spanish Cultural Center, 1939–1984, 827 Broadway; (4) Aurelio Rodriguez Photography Studio, 1935–1950, 802 Broadway; (5) Luz Garcia’s Club Sinaloa, 1930s–c. 1976, 1416 Powell Street; (6) La Mexicana, grocery, 1930s–1960s, 799 Broadway; (7) Xochimilco, Mexican restaurant, 1940s, 787 Broadway; (8) Basque Boardinghouses (Hotel de España, Globo Hotel, Jai Alai, Hotel Pyrenees, Hotel Español / Martin’s Español), c. 1908–1950s, 719–785 Broadway; (9) El Chico Club, 1950s, 681 Broadway; (10) Caliente Club, 1940s–1950s, 675 Broadway; (11) Tijuana Cantina, 1950s–1960s, 671 Broadway; (12) The House That Jack Built, late 1950s (founded c. 1930s), 670 Broadway; (13) La Moderna Poesia / Sanchez Spanish Books and Music, 1930s–1950s, 658 Broadway; (14) Teatro Verdi, 1915–1954, 644 Broadway; (15) Nuestra America Books and Music, 1930s–1950s, 621 Broadway; (16) Mambo Café, 1950s, 347 Columbus; (17) El Cid Cafe, c. 1960–c. 1981, 606 Broadway; (18) City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1953–, 261 Columbus; (19) Vesuvio’s (Beat hangout), 1949–, 255 Columbus; (20) Finocchio’s (female impersonators), 1936–1999, 506 Broadway; (21) Vanessi’s, 1936–1986, 498 Broadway; (22) El Matador, c. 1953–1977, 492 Broadway; (23) Mona’s Candlelight (lesbian bar), 1948–1957, 473 Broadway; (24) Chi Chi Club, 1949–1956, 467 Broadway; (25) Club 440 / Mona’s (lesbian bar), 1939–1948, 440 Broadway; (26) Casa Madrid, 1960–late 1970s, 406 Broadway; (27) El Patio (Mexican), 1930s–1950s, 404 Broadway; (28) Basin Street West (jazz club), 1964–1973, 401 Broadway; (29) International Settlement (block of “international” clubs), 1940s–1957, 500 Pacific block.

Prior to the Mission, Latino-themed businesses and social spaces in the Latin Quarter made the neighborhood one of the more visible Latino enclaves in the city. In the 1940s and 1950s, a row of restaurants and nightclubs on Broadway promoted live music, floor shows, and dancing, often accompanied by the rhythmic sounds of the mambo, rumba, or flamenco. The promotion of a Latin nightlife gave Latino musicians and performers important cultural and commercial opportunities in the 1940s and 1950s. Even so, these entertainment spaces relied on celebratory expressions of Latino culture that were often at odds with the realities of Latino lives. Gradually, the commodification of Latino cultures and nightlife participated in and overshadowed the steady displacement of Latino residents.

“Real Life” in San Francisco’s Latino Communities

In the first half of the twentieth century, the Latin Quarter served as the public space for all things Mexican in San Francisco. Clarence Edwords, author of a 1914 culinary tour of San Francisco, cited the area around Broadway and Grant Streets in North Beach as the place to learn “something about conditions in Mexico.” Edwords wrote: “Here you will find all the articles of household use that are to be found in the heart of Mexico. . . . You will find all the strange foods and all the inconsequentials that go to make the sum of Mexican happiness, and if you can get sufficiently close in acquaintance you will find that not only will they talk freely to you, but they will tell you things about Mexico that not even the heads of the departments in Washington are aware of.”6 As Edwords observed, a visible and politicized Mexican community existed in the Latin Quarter. Some even adopted the term “Little Mexico” to describe the population that resided at the base of Telegraph Hill and along Broadway around Montgomery and Kearny streets.7

However, the descriptions often displayed little appreciation for Mexican culture. The only two Mexican restaurant reviews featured in Edwords’s book were damning, reporting that “the cooking was truly Mexican for it included the usual Mexican disregard for dirt,” and on the other, “they were strictly Mexican, from the unpalatable soup (Mexicans do not understand how to make good soup) to the ‘dulce’ served at the close of the meal.”8 In the writings of Edwords and most city records, neither Mexicans nor Mexican food ranked high in public esteem, but these passing observations did confirm the presence of a Mexican population in the Latin Quarter.

Though the Latin Quarter served as the nominal public space for Mexican culture, Latino residents made their home in residential spaces throughout the city. Referring to 1930s San Francisco, Austin wrote, “There are no distinct colonies of South Americans. They settle in the neighborhoods where they can find the Spanish language spoken in shops and restaurants operated for the Spaniard and the Mexican. Thus we find them living in North Beach, in the Mission and about Fillmore Street.”9 Austin’s comment indicated the sometimes hazy lines of racial segregation prior to World War II. The interspersal of small communities, or colonias, was typical of Mexican settlement in many major U.S. cities in the early twentieth century.10 Segregation perpetuated these colonias, but city residents had not fully crystalized the more formal lines of neighborhood segregation that defined urban life after World War II. California and the entire Southwest bear a long history of alternating between suppressing and romanticizing the region’s Mexican heritage.11 The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo initiated a long period of subjugation of Mexican residents, many of whom, through physical, economic, and cultural force, lost their land and experienced various forms of disenfranchisement from their U.S. citizenship.12 In The Annals of San Francisco, the sensationalist 1855 sourcebook on San Francisco’s Gold Rush, the authors declared: “Hispano-Americans, as a class, rank far beneath the French and Germans. They are ignorant and lazy, and are consequently poor. . . . The Mexicans seem the most inferior of the race. . . . The most inferior class of all, the proper ‘greaser,’ is on par with the common Chinese and the African; while many Negroes far excel the first-named in all moral, intellectual and physical respects.”13 Such negative representations contributed to various forms of violence directed at Mexican Americans, including lynchings and rapes.14 Social devaluation was even evident in the pricing at a nineteenth-century bordello, the Municipal Crib, which charged half as much for Mexican women as for Anglos and African Americans (twenty-five cents versus fifty cents).15 Stereotypes of Mexicans and Mexican Americans portrayed them as undesirable and among the lowest class of Latin Americans.

The migration of Mexicans fleeing the revolution during the 1910s contributed to negative public representations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans; these new immigrants, tending to have little cultural capital in terms of U.S. education, economics, and English language skills, were delegated the least attractive jobs and lowest social status.16 Over the course of the 1920s and early 1930s, Mexican migration into the United States continued to increase. The Cristero movement played a role. In 1926, the Cristeros, as self-labeled “followers of Christ,” rejected the Mexican government’s open hostility to the Catholic Church. The ensuing execution of priests and other pious Catholics horrified people around the world and spurred acts of solidarity.17 Though Austin did not refer to the Cristeros by name, he did describe the recent settlement of many Catholics in San Francisco as a product of discrimination in Mexico.18 The long-standing Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe) church served as the most welcoming place in San Francisco for these religious refugees (Fig. 1.2).

The grandeur of the church offers some indication of the many parishioners who stepped through its doors to attend regular Spanish services. An earlier church was built in 1880 but destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Its 1912 replacement dominated the street with two towering cupolas and an enormous carved frontispiece in the style of California’s oldest missions. The motif reflected a trend toward Spanish colonial revival architecture and underscored the “Spanish” heritage of its parishioners. The building is now hidden behind the 1950s construction of the Broadway tunnel, a major thoroughfare through the base of Russian Hill that substantially displaced its parishioners.

In name, Our Lady of Guadalupe church paid homage to the indigenous Mexican representation of the Virgin Mary, thereby speaking directly to the religious beliefs of its Mexican parishioners. In fact, the yearly celebration of the virgin on December twelfth may be the longest-running Mexican-oriented event in the Bay Area, though it is hard to pinpoint the date of the first celebration.19 By providing services in Spanish, the church attracted diverse immigrants of Spanish-speaking countries. The pastor of the church from 1889 to 1944, Monsignor Antonio M. Santandreu, was from Barcelona and could speak directly to the needs of his many Basque and Spanish parishioners.20

Figure 1.2. Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, or Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, August 12, 1924. According to the original caption, the class outside was about to participate in “forty hours devotional service” in Spanish. This two-day ritual, also known as Quarant’Ore, encouraged additional expressions of faith, rather than strict attendance for forty hours. Image courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

People of Mexican origin were in the majority, but they did not easily dominate the Latino population. The 1930 census—the only census to distinguish Mexicans as a race—reported a little...