![]()

Chapter 1

Capitalism and the Crisis: Bankers, Bonuses, Ideology, and Ignorance

JEFFREY FRIEDMAN

I am privileged to introduce not only the first collection of scholarly essays devoted entirely to the question of what caused the financial crisis of 2008, but a collection that brings us much closer to a comprehensive answer.

As a proxy for the level of scholarly advance achieved in these pages, note that the claims of our distinguished contributors can, in the main, be fit into a larger mosaic with little friction between the pieces. It is true that some of our authors blame the crisis on government action while others blame it on government inaction. But the two types of claim are not mutually exclusive. Both action and inaction can be the result of government policy and, for the most part, that is how our authors treat the causes of the crisis: as policy failures, whether failures of action or of inaction. Thus, it may be said that, for the most part, our contributors agree that this was a crisis of politics, not economics.

Thus, no contributor argues that the Great Recession was just a normal business-cycle downturn or even a normal popped asset bubble: As Steven Gjerstad and Vernon L. Smith point out in Chapter 3, asset bubbles inflate and burst frequently, but worldwide near-depressions are rare. Obviously the crisis took place within “the economy,” but our authors mostly agree that special, noneconomic causal factors were at work—political factors—regardless whether one names policies that backfired (as do the authors of Chapters 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) or policies that could have been imposed but were not (as do the authors of Chapters 2, 3, 4, 11, and 13).

Which brings us to the elephant in the anteroom. Granting that the financial crisis was not a typical economic fluctuation, and granting that both regulatory action and regulatory inaction may have played a role, the intellectually (and politically) important question is whether it was nonetheless a crisis that can be attributed to “capitalism.” This is the question that interests people around the world who would not otherwise care what caused a given financial downturn; and it is a question that does divide our authors. Yet none of their chapters, which deal with some of the most important individual causes of the crisis, are designed, for the most part, to give a detailed answer to that larger question.

In the interest of providing such an answer, this introduction will consider the big picture to which the individual papers contribute, even at the risk of violating Daron Acemoglu’s injunction in Chapter 11, echoed in a sense by Richard Posner in the Afterword, to recognize that capitalism is, of necessity, constrained (and constructed) by law. This is undeniably good counsel, but the larger issue raised by the crisis is whether, without close regulatory supervision, capitalism is prone to implode. Clearly this was a crisis of regulated capitalism, but the pressing question is whether it was the capitalism or the regulations that were primarily responsible. Contrary to Posner’s implication, I believe it is possible to separate the capitalist and the regulatory contributions to the crisis, just as it is possible to advocate “more” or “less” regulation of capitalism without ignoring the fact that even “laissez faire” capitalism is, at bottom, a system of laws—that is, of regulations.

The Subprime Bubble and Housing Policy

The deflation of the subprime bubble in 2006–7 was the proximate cause of the collapse of the financial sector in 2008. So one might think that by uncovering the origins of subprime lending, the causes of the financial crisis would have thus been identified. But as we shall see, subprime lending is only the beginning of the story. Since our ultimate objective is to explain a banking crisis, we need to understand not only where subprime and other elements of the housing bubble originated, but how they came to be overconcentrated in the banking system. Part II will address why the bursting of the bubble brought down the financial system and, in turn, the “real” (nonfinancial) economy of most of the world. Part III will discuss whether the banks’ compensation systems or their self-perception as “too big to fail” motivated bankers to take excessive risks. Part IV turns to the question of whether capitalism should be held responsible for the banking crisis; and Part V asks whether regulation should be held responsible.

The Limited Relevance of Federal Housing Policy

Chapter 6 attempts to pin the blame squarely on the government, not capitalism. The main culprits it identifies are the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

New regulations governing the enforcement of the CRA, issued in 1995, did cause subprime lending, but the question is, how much? First enacted in 1977 in an effort to rectify racism (“redlining”) in mortgage lending, the CRA was revised in 1995 to require that all FDIC-insured mortgage-lending banks (for purposes of this introduction, “commercial” banks, including savings and loans) prove that they were making active efforts to lend to the underprivileged in their communities. Chapter 6 allows, however, that most subprime lending did not occur under CRA auspices. According to the Superintendent of Banks for the State of New York, only 6 percent of subprime loans were issued by banks subject to the CRA (Neiman 2009). This is because most subprime mortgages were originated in the “shadow banking system,” that is, by mortgage specialists such as Countrywide and New Century rather than by commercial banks such as Wells Fargo, Citibank, and JPMorgan Chase (Gordon 2008).

However, Chapter 6 argues that the new CRA regulations were only one aspect of a government-wide effort to expand homeownership rates among minorities and the poor. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) were substantial contributors to this overall effort, under directives from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Fannie Mae had been created by Congress in 1938 to repurchase mortgages from commercial banks so that banks would be more willing to issue them. Fannie was pseudo-privatized in 1968 to move it off the federal government’s budget; in 1970, it was joined off-budget by another congressional creation with a similar homeownership agenda, Freddie Mac. Although shares in these GSEs were owned by private investors after 1968, their congressional charters suggested that if they got into trouble, Congress would bail them out (as it did, in September 2008). This implicit federal guarantee enabled them to borrow money more cheaply than private competitors.

In 1995, HUD ordered Fannie and Freddie to supplement the FHA’s efforts to expand homeownership, and eventually to far surpass them, by directing 42 percent of their mortgage financing to lowand moderate-income borrowers (Johnson and Kwak 2010, 112). In response, Fannie Mae introduced a 3 percent-down mortgage in 1997. Traditionally, non-FHA, GSE mortgages had required 20 percent down, giving them an initial loan-to-value ratio (LTV) of 80. (A mortgage requiring no down payment would have an LTV of 100.) But such large down payments were the biggest barrier to home ownership among the poor. Higher-LTV mortgages made housing more affordable.

Strictly speaking, the “subprime” label applies solely to the credit score of the borrower, not the terms of the mortgage. Fannie and Freddie were prohibited from making this type of subprime loan. But high-LTV loans were, at least when insured by the GSEs, designed to help impoverished borrowers with spotty employment histories and thus low credit scores. There was thus a great deal of overlap between high-LTV mortgages and subprime mortgagors. The average LTV of a subprime loan issued in 2006 was 95 (i.e., a 5 percent down payment). By that point, high-LTV loans had also been extended to borrowers with better-than-subprime credit scores, such as “Alt-A” mortgagors, who barely missed the criteria for a “prime” loan (or whose income or assets were under-documented). In 2006, the average Alt-A LTV was 89 (Zandi 2009, 33). Such “nonprime” mortgages played a significant role in what is more loosely called the “subprime” bubble. Unless the context calls for more precision, I will employ that looser usage here.

In 2000, HUD increased the GSEs’ low-income target to 50 percent (Johnson and Kwak 2010, 112); in the same year, Fannie launched “a ten-year, $2 trillion ‘American Dream Commitment’ to increase homeownership rates among those who previously had been unable to own homes” (Bergsman 2004, 55). Freddie Mac followed, in 2002, with “Catch the Dream,” a program that combined “aggressive consumer outreach, education, and new technologies with innovative mortgage products to meet the growing diversity of homebuying needs” (Bergsman 2004, 56). In 2004, HUD increased the target again, to 56 percent (Johnson and Kwak 2010, 112). In the end, as Chapter 6 shows, about 40 percent of all subprime loans were guaranteed by the GSEs.

In 2006, house prices began to level off and, in some places, fall. Subprime mortgagors began to default at higher-than-expected rates. By the summer of 2008, it was clear that this trend threatened the solvency of the GSEs, and on September 9, 2008, Fannie and Freddie were bailed out—just as had been expected, because of their government-sponsored status. However, precisely because they were bailed out, they cannot be said to have caused the worldwide financial panic that began a week later, when Lehman Brothers, the huge investment bank, declared itself insolvent. The bailout of the GSEs was certainly expensive—upward of $382 billion (Timiraos 2010)—but this expense merely added to the growing fiscal deficit of the U.S. government, which may cause a crisis in the future but did not cause the crisis of 2008. Indeed, the GSE bailout had the positive effect of removing the biggest risk that had been caused by the bursting of the subprime bubble: the possibility that commercial banks would become insolvent because they held $852 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) issued by Fannie and Freddie (Table 7.1). These securities bonds are called “agency” bonds to distinguish them from MBSs issued by investment banks (such as Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and Goldman Sachs), which are called “private label” MBSs, or PLMBSs.

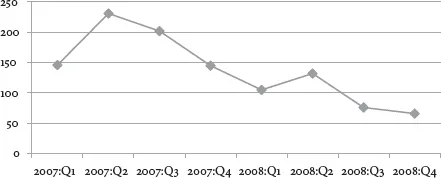

Figure 1.1. Decline in U.S. commercial lending during the crisis ($ billion). Real investment loans are intended for general corporate purposes, capital expenditure, or working capital. Data provided by Victoria Ivashina and David Scharfstein, compiled from DealScan database.

On the other hand, the post-Lehman panic was only the peak of a banking crisis that had been brewing for more than a year and a half. Figure 8.13 shows that doubts about subprime mortgages were already being reflected in the cost of insuring PLMBSs in January 2007. These doubts began to raise the cost of insuring the subprime securities predominantly held by commercial banks—the ones rated AAA—in June 2007. That is when commercial-bank lending to businesses began to decline, a decline that had more than halved new business lending by the end of 2007. It would be halved again by the end of 2008 (see Figure 1.1). The decline in lending is widely held to have been the direct cause of the Great Recession. It is quite possible that commercial banks were as worried about their holdings of agency securities as of private-label securities, and that until Fannie and Freddie were bailed out, this contributed to the banks’ reluctance to lend, and thus to the recession. It is a ripe topic for future research.

What is more certain is that Fannie and Freddie used the borrowing advantages conferred upon them by their quasi-official status to pump up the housing bubble—not just the subprime portion of it. The GSEs accounted for 41 percent of all mortgages in the United States by the time the bubble burst (Table 7.1). This is important because the more buyers there are in a bubble, the higher prices go—and the farther they fall when the bubble deflates; and because the higher the price of a house, the larger the mortgage needed to buy it. (Thus “jumbo” loans, too big for the GSEs, became more common as the decade continued.) The higher the mortgage, the more tempting it is to put down a small down payment or to use the low initial rate offered by an adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM). Most important, though, the larger the mortgage, the more unaffordable it will be to the mortgagor if push comes to shove—for instance, if the interest rate on an ARM begins to rise, or the price of a home begins to fall.

Mortgage Securitization in the Private Sector

Private-sector lenders, including both commercial banks and mortgage specialists, originate all U.S. mortgages. Fannie and Freddie bought 41 percent of them for securitization, but the other 59 percent either stayed with the bank of origination or were sold for securitization to investment banks. Like the GSEs, the investment banks securitized mortgages—turning pools of hundreds of them at a time into mortgage-backed securities—by selling shares of the future principal and interest payments to investors around the world. From an investor’s perspective, the main difference between an agency MBS and a PLMBS was that the latter, lacking the U.S. government’s implicit guarantee, instead had various ratings to signify how safe it was. AAA is the highest rating a bond can get, and an MBS is an asset-backed bond. A bond is a promise to pay the bearer a certain interest rate over a period of years. An MBS is a bond in which the source of the interest payments is not, as with other bonds, a government or a corporation, but a pool of assets: the mortgages.

To produce the ratings on PLMBSs, investment banks worked with bond-rating agencies to divide the income from a pool of mortgages into different “tranches,” or segments, which were assigned payment priority over each other, in what was called a “waterfall.” Investors in the top, “senior” tranche would get paid before any other investors in the MBS; that tranche was rated AAA. (Sometimes there were even tranches that were senior to the triple-A tranche; these were called “super-senior” tranches.) After senior investors had received all of the payments promised to them, income from the pool would flow down to the AA tranche, then the A tranche, then the BBB tranche.

There was also an unrated equity tranche to provide extra safety to the investors; this was known as “overcollateralization.” The mortgages in the rated tranches were the collateral that ensured payments to the bondholders; but if any of the mortgagors were delinquent (late) in their payments, or if they defaulted by stopping payments altogether, the extra collateral would pick up the slack before any investors suffered diminished income. After the overcollateralization was exhausted, if reselling foreclosed houses did not recover all the lost revenue, then investors in the juniormost (B) tranche would be the first to suffer interruptions in their guaranteed payments, since these investors were the last to be paid. In turn, these investors’ income from the PLMBS would have to be completely halted by defaults or delinquent payments throughout the mortgage pool before investors in the next-most-junior tranche suffered any losses, and so on up the line, with the triple-A tranche being insulated from loss by all the subordinate tranches. Thus, in a typical MBS with a 2 percent equity tranche, investors in the BBB tranche would begin to experience reduced payments if more than 2 percent of the mortgage holders in the pool made late payments or stopped making payments altogether—except that even when a mortgagor “walks away” from a mortgage, the house is recovered and resold. Thus, when one adds the equity tranche to a typical BBB tranche covering 3 percent of the mortgage pool, an A tranche covering 4 percent, and an AA tranche covering 11 percent, it would be difficult for losses to reach the AAA tranche, even though this tranche typically covered 80 percent of the mortgage pool (IMF 2008, 60, Box 2.2). “It had been typical to assume that when a subprime mortgage foreclosed, about 65 percent of its outstanding balance could be recovered. Such a 35 to 50 percent loss-severity assumption implied that from 50 to 65 percent of the mortgages would have to default before losses would impact the MBS senior tranche” (IMF 2008, 59).

Given all the protection for the senior tranche, the obvious question is why anyone would buy a bond in a junior or “subordinate” tranche. The answer is that, in exchange for the higher risk they bore, investors in the subordinate tranches received higher rates of return, just as investors in junk bonds receive higher rates of return than do investors in “investment-grade” bonds. An investor could therefore choose to take a lot of risk on a subordinate tranche in exchange for a lot of income; or could instead minimize risk by investing in a senior tranche that paid less income.

The workings of structured securities have often been portrayed as being too complicated to understand, but they are really quite simple, and the reasoning is valid. Within any given pool of mortgages, even if 99 percent default, 1 percent of the investments in the pool would be justified (ex post facto) in being rated AAA. For this reason (and others to be discussed), tranching was extremely popular with investors. Eventually investment banks devised collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which tranche...