![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE CHALLENGE OF THE DEPRESSION

DURING the 1920s, Urbain Ledoux opened “the Tub” on St. Mark’s Place on the Lower East Side. Known as “Mr. Zero,” the businessman turned philanthropist offered meals and lodging to New York’s homeless men. A Buddhist, Ledoux felt called to work among the poor. He had begun his efforts in New England, selling the unemployed at “slave auctions” on Boston Common. By March 1928, Ledoux reported lodging over 1,140 men nightly in steamer chairs while feeding 2,000 from a five-cent basement soup kitchen and a ground floor cafeteria. Espousing his own brand of radical politics, Ledoux proposed outlandish schemes such as auctioning the labor of the unemployed to Midwestern farmers, who might repay him in grain to use to feed the poor.1

As the Depression deepened, Ledoux used publicity creatively to highlight the plight of the Bowery’s homeless. Large Thanksgiving meals earned the Tub mention in the annual newspaper coverage of charitable holiday programs. In the spring, Ledoux led a contingent of homeless men marching in the famous Fifth Avenue Easter parade. The bedraggled marchers inspired journalists to contrast New York’s wealthy and its poor: “Mr. Zero and the ‘boys’ from the Tavern arrived in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral at noon and displayed what the unemployed man will wear this season. Their garb was traditional, in keeping with last year and the years before it—battered plug hats, lumberjackets, frayed trousers and shoes that had more than their share of walking the streets.”2

Ledoux’s colorful efforts reflected the collapse of the city’s relief system. By 1929, the existing network of charitable assistance and commercial lodgings, sufficient for decades, had strained and broken under the crushing tide of poverty and homelessness. City officials and charity administrators looked on in horror as poor people spread across the urban landscape, squatting in shacks, lining up for bread, begging for cash, and marching in protest. Who should provide assistance to these crowds of people? Some were the established poor, who had been homeless even before the Depression had begun. Previously, they had been helped, as the poor of other cities had also been, by a network of ethnic and religious associations bolstered by a few public organizations. Now, as throngs of the newly poor—pushed out of the security of the middle- and working classes by the economic devastation brought on by the Depression—crowded into such institutions, the existing networks could not keep up with the demand. The dramatic increase in poverty during the late 1920s and early 1930s shocked city and state officials into action, prompting them to begin developing a new, increasingly publicly funded, philosophy of relief.

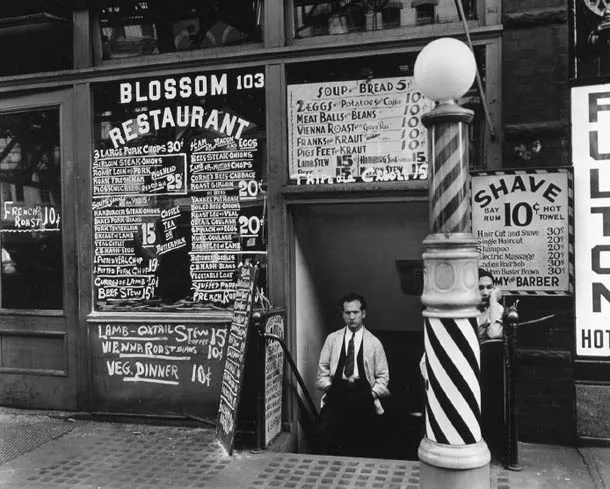

Figure 7. In this iconic work for the Federal Arts Project, Berenice Abbott photographed the extensively detailed menu of inexpensive food served on the Bowery. “Blossom Restaurant, 103 Bowery, Manhattan,” 1935. Copyright The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY.

Life on the Bowery

In the 1920s, a young white man without shelter might spend the night at the Bowery Branch YMCA on East Third Street. The organization promoted Protestant Christianity, but nearly half the residents were Roman Catholic. If admitted, he could attend lectures, discussion groups, and weekend trips to the country and the beach with other members, half of them under thirty. Most likely, though, he would find the casework approach of the YMCA invasive, and would continue looking for a facility offering him a bit more freedom.3

Leaving the YMCA and walking south down through the Bowery, he would encounter an array of establishments vying for his business. He might pause to read the menu painted in the windows of a corner restaurant. He might stop in at the Holy Name Mission for counsel or a place to rest. If he hoped for simple lodging and to be left alone, he might rent a room next door at the Arcade Hotel. Walking farther, he could see used suit jackets hanging in secondhand clothing shops, and might buy one for an upcoming job application. He could visit one of the many barber shops and barber schools that lined the street, their characteristic striped signs promising a discounted shave or haircut. Below Bleecker Street, flophouses and missions lined the streets. Between Houston and Delancey Streets, the eye was overwhelmed by the sea of signs announcing hotel names, including the Montauk, Savoy, and Puritan. Along the sidewalk, an informal “thieves’ market” of used and stolen goods was thriving. Next door to the Salvation Army’s Memorial Hotel, the Bowery Mission had occupied 222 Bowery since 1908. The building’s second-floor stained-glass windows reminded those inside and out of God’s constant presence there.

Looking uptown from Houston Street, peering between the elevated railroad tracks and the four-story Bowery facades, he would see the stately Metropolitan Life building silhouetted against the sky. Although only a few miles apart, mostly prosperous Midtown and the gritty Bowery hardly seemed part of the same city. Near Grand Street, he would see remnants of the area’s own deep and eclectic architectural past. Several businesses occupied the ground floors of Federal-era townhouses. Everyone noticed Stanford White’s bold Roman classical style 1895 Bowery Savings Bank. The building’s massive fluted Corinthian columns were topped by a pediment featuring figures sculpted by Frederic MacMonnies. Such grandeur seemed out of place on skid row.4

One had to walk gingerly to avoid tripping on the products displayed in front of hardware and fixtures stores, the sandwich boards promoting inexpensive meals, or the groups of men sitting or sometimes collapsed on the sidewalk. Near Canal Street, one also had to avoid the huge bales of paper outside the Jewish Press Publishing Company. Both sides of the street were crowded with jewelry stores and more cheap hotels, barber colleges, bars, and movie theaters. The journey down the Bowery concluded past the Owl Hotel, where tattoo studios also offered to conceal black eyes. Near Chatham Square, the Bowery’s official terminus, the All-Night Mission offered salvation and soup to those who sought help.

Figure 8. Photographer Berenice Abbott captured the shadowy realm of the Bowery, where the sun rarely penetrated beneath the tracks of the elevated trains. “El, Second and Third Avenue Lines,” 1936. Copyright Museum of the City of New York.

The Bowery was not the only place in the city where homeless white men found accommodations and assistance. In one notable example, the Mills Hotel Trust operated three large facilities downtown, containing a total of more than 4,000 rooms and costing from thirty to fifty cents per night. On Blackwell’s Island, the New York City Home for the Aged and Infirm housed invalid men and women, and others unable to work. When full, the massive facility lodged over 900 men and nearly 1,200 women. The muni on 25th Street also continued to welcome both men and women. But the Bowery had developed into a skid-row district, attracting the homeless not just to a single facility, but to sixteen blocks of flophouses, missions, cheap restaurants, and bars.5

White women found far fewer options on the Bowery. If she had money, a homeless white woman might dine in area restaurants, or drink in bars alongside her male companions. Many flophouses did not permit women residents. If she was over fifty and had twenty-five cents, however, she might spend the night at the Glendon Hotel at 243 Bowery, six doors north of the Bowery Mission. Beginning in 1898, the facility had been maintained by the Salvation Army, but by the mid-1920s it was privately owned. Flanked by a dingy restaurant and a shop selling store fixtures, the five-story building housed approximately sixty women, most of whom worked as peddlers or maintenance workers. Entering the hotel door, she would immediately mount a steep staircase to the second-floor cashier’s window. The sitting room drew lodgers, who clustered around a black stove or sat near the windows. The hotel operator sympathized with her charges, yet described them as feisty: “I feel sorry for them myself. If one of them does get a little drunk I don’t chase her out if I can handle her. I try to get her quiet and put her to bed. It’s not so easy, running the house, believe me! My husband’s got a man’s lodging house next door. He’d rather run that than this any day. One drunken old woman can rave and cuss so she wakes up the whole dormitory, and first thing you know they’re all shouting and cussing at one another.”6

Young white women found aid across Manhattan. The Children’s Aid Society sponsored an array of facilities, including the small Shelter for Women with Children on East 12th Street. Some organizations offered lodgings for a fee. Up to one hundred and ten “respectable, self-supporting young women under 40” could be lodged in double rooms at the Eastside Anthony Home. Spanish-speaking young women were welcome at the Fourteenth Street Casa Maria, sponsored by the Augustinian Fathers of the Assumption. A few facilities were remarkably open in their admissions policy, such as the City Federation Hotel on 22nd Street, which offered board and lodging for up to fifty-six women of any race. Other facilities focused on working-class women, such as Maedchenheim on East 62nd Street, home to “domestic service girls.”7

Some institutions had restrictive and starkly class-based policies. The 104th Street Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged and Indigent Females home refused applicants who had “lived as servants.” Entry also required a $300 fee and the promise of all one’s property at death. In the Bronx, the West Farms Peabody Home for Aged and Indigent Women welcomed up to thirty-two Protestant women over age sixty-five, but cautioned, “domestic servants and colored women excepted.”8

African Americans found few welcoming facilities on the Bowery. Many hotels and restaurants discriminated against non-whites. Charitable organizations also maintained segregated referral systems, sending African American applicants most often to Harlem, the Bronx, and Brooklyn for aid. Facilities like the Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People, for instance, welcomed those over sixty-five.9

African American women’s charity resources clustered in Harlem. St. John’s House for Working Girls (sponsored by the Cathedral of St. John the Divine) offered lodgings to “worthy but poor colored girls,” as did the Sojourner Truth House and the White Rose Mission and Industrial Association. The YWCA had operated in Harlem since 1905. It ran smaller residences until it opened Emma Ransom House in 1926, with over two hundred beds and impressive amenities including an elevator and laundry service.10

These mostly smaller, private charities reflected the commitment to individualism and voluntarism that typified American philanthropy before the Depression. Many organizations were designed to aid individuals of a specific ethnicity, which usually emerged from a mixture of ethnic pride and reaction to prejudice. The Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Emigrant Mission and Emigrant Home on Whitehall Street, for instance, offered temporary lodgings to arriving Norwegians.11

Jewish New Yorkers developed especially elaborate charity networks that reflected two distinct religious and cultural philosophies of assistance. German Jews established the Homeless Men’s Department of the Jewish Social Service Association in 1922. The organization used intensive screening interviews and background checks before providing assistance and referrals. By contrast, the Hebr...