![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Ideology of the Republican Party

Eric Foner

In August 2000, the Republican party gathered in Philadelphia for its national convention, and nominated George W. Bush for president. Few delegates realized that the party's first national nominating convention, in 1856, also took place in the City of Brotherly Love. But that party was a far different institution from its counterpart today. The sight of a Republican presidential candidate from Texas and a Republican leader of the Senate from Mississippi would certainly have surprised the party's founders. So too would the sight of the party that saved the Union and emancipated the slaves embracing the Old South's doctrine of state sovereignty and expressing deep hostility to civil rights enforcement, to affirmative action—indeed, to any measures that seek to redress the enduring consequences of slavery and segregation. Nonetheless, in some ways we still live in a world shaped by the achievements of the early Republican party—the destruction of slavery, preservation of the Union, and establishment of a national principle of equal rights for all Americans.

In my first book, I argued that the key unifying principle of the Republican party before the Civil War was opposition to the expansion of slavery.1 Few Republicans, to be sure, should be classified as abolitionists—critics of slavery who called for immediate emancipation and equal rights for black Americans. The abolitionists never commanded more than a small fraction of the northern public. But they helped create a public opinion hostile to slavery and especially to its further expansion.

When Congress in 1854 approved the Kansas-Nebraska Act, repealing the Missouri Compromise and opening a vast new area in the nation's heartland to slavery, party lines shattered and a new organization, the Republican party, rose to prominence on a platform of stopping slavery's expansion once and for all. In the new party, belief in the superiority of the “free labor” system of the North and the incompatibility of “free society” and “slave society” coalesced into a comprehensive world view or ideology. The distinctive quality of northern society, Republicans insisted, was the opportunity it offered wage earners to rise to property-owning independence. Slavery, by contrast, was an obstacle to progress, opportunity, and democracy. No one expressed this vision more eloquently than Abraham Lincoln. Having served a number of terms in the Illinois legislature and two years in Congress in the 1840s, Lincoln had retired from active political involvement in 1849. He was swept back into politics by the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Lincoln once remarked that he “hated slavery, I think as much as any abolitionist.” Yet he was not an advocate of immediate emancipation. He revered the Union and the Constitution and was willing to compromise with the South, including the much-despised Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, to preserve them. Moreover, he shared many of the era's racial prejudices, affirming in 1858 that he did not favor blacks' voting or holding office in Illinois, and frequently speaking of colonizing African Americans outside the country. In this he represented the mainstream of white northern opinion, by now convinced that slavery posed a threat to “free society,” but still convinced of the inherent inferiority of African Americans. But Lincoln also believed that the nation could not survive forever “half slave and half free,” and he insisted that the founders had intended to place the peculiar institution on the road to “ultimate extinction.” Like the abolitionists, Lincoln maintained that slavery violated the essential premises of American life—personal liberty, political democracy, and the opportunity to rise in the social scale. “I want every man to have the chance,” he proclaimed, “and I believe a black man is entitled to it, in which he can better his condition.” And, like the abolitionists, Lincoln insisted that America's professed creed was broad enough to encompass all mankind. When his opponent in the celebrated 1858 Illinois Senate race, Stephen A. Douglas, proclaimed that the United States government was created “by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever,” Lincoln responded that the rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence applied to “all men, in all lands, everywhere,” not merely Europeans and their descendants. Blacks, he added, might not be equal to whites in all respects, but in their “natural right” to the fruits of their labor, they were “my equal and the equal of all others.”2 It ought not to be surprising that when Lincoln won election as president in 1860, seven southern states concluded that slavery would not be safe under his administration.

The Civil War reinforced many elements of the Republicans' prewar ideology, while subtly transforming others. Despite his antislavery convictions, Lincoln's aim in the first year of the war was to retain the loyalty of the border slave states, secure the largest base of support in the North, and attract wavering white southerners to the Union cause. All these goals would, he felt, be compromised by making the destruction of slavery a war aim. But many factors, beginning with the actions of the slaves themselves in abandoning plantations as soon as the Union army made its appearance, converged to make the initial policy untenable. From the outset of the war, many northerners, especially abolitionists and Radical Republicans in Congress, insisted that, as the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy (the oft-cited phrase employed by the South's vice president, Alexander H. Stephens), slavery must become a military target. In 1862, as the disintegration of slavery continued, the danger of losing the border states receded, the manpower needs of the Union military continued to grow, and success on the battlefield continued to elude Lincoln's armies, pressure for emancipation mounted. In March 1862, Congress prohibited the army from returning fugitive slaves. Then came abolition in the District of Columbia and the territories, followed by the Second Confiscation Act, which liberated slaves of disloyal owners in Union-occupied territory. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It did not liberate all the slaves. With the exception of the South Carolina Sea Islands, occupied by the Union navy in November 1861, it applied only to areas under Confederate control. Excluded from its purview were nearly half a million slaves in the border states, and more than 300,000 in Tennessee and parts of Virginia and Louisiana. But the vast majority of the nation's slave population, more than three million men, women, and children, declared the Proclamation, “are and henceforth shall be free.”3

The old image of Lincoln singlehandedly abolishing slavery with the stroke of his pen has long been abandoned, for too many other Americans—politicians, reformers, soldiers, and slaves—contributed to the coming of emancipation. Yet the Emancipation Proclamation profoundly altered the nature of the war, the future course of American history, and the Republican party's ideology. The Proclamation transformed a war of armies into a conflict of societies, and ensured that Union victory would produce a social revolution within the South and a redefinition of the place of blacks in American life. There could now be no going back to the prewar Union. A new system of labor, politics, and race relations would have to replace the shattered institution of slavery, and a new status for the former slaves would have to be worked out. Emancipation, in other words, made a revolution in southern life and an era of Reconstruction inevitable.

The Emancipation Proclamation represented a turning point in Lincoln's own thinking. It contained no reference to compensation to slaveholders or colonization of the freedpeople—issues he had promoted before 1863. And for the first time it announced that black men would be enrolled into military service. In the end, black soldiers played a crucial role not only in winning the Civil War but also in defining the war's consequences. More than any other single development, military service, as Frederick Douglass had anticipated, placed the question of black citizenship on the national agenda. The inevitable consequence of enrolling black men in the army, one U.S. senator observed in 1864, was that “the black man is henceforth to assume a new status among us.” The service of black soldiers affected the outlook of Lincoln himself. He insisted that they must be treated the same as whites when captured by the Confederacy (the southern government had declared that black soldiers would be deemed rebellious slaves, not prisoners of war, and sold into bondage). When the Confederacy refused to include captured blacks in prisoner-of-war exchanges, Lincoln suspended the entire program rather than admit a racial distinction among the men who fought and died for the Union. In 1864 Lincoln, who before the war had never supported suffrage for African Americans, urged the governor of Unionist Louisiana to work for the partial enfranchisement of blacks, singling out former soldiers as especially deserving. At some future time, he observed, they might again be called on to “keep the jewel of Liberty in the family of freedom.”4

Racism was hardly eradicated from national life. During the New York City draft riots in 1863, black men, women, and children were hunted by mobs and lynched on the streets of the nation's commercial metropolis. Yet by the war's end many Republicans had come to embrace the old abolitionist view that the abolition of slavery must bring not only an end to bondage but a national citizenship whose members enjoyed the equal protection of the laws regardless of race. Indeed, one of the first acts of the federal government to recognize the principle of equality before the law was the decision, as the war drew to a close, to grant black soldiers retroactive equal pay with their white counterparts.

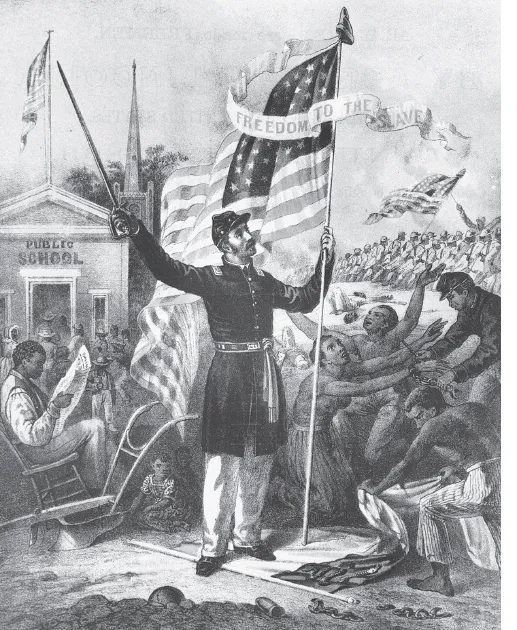

Figure 1.1. Freedom to the Slave, colored lithograph (n.p., 1863?). The reverse of this depiction of black soldiers fighting for freedom is a recruiting poster for black troops: “All Slaves were made Freemen. By Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, January 1st, 1863. Come, then, able-bodied Colored Men, to the nearest United States Camp, and fight for the Stars and Stripes.”

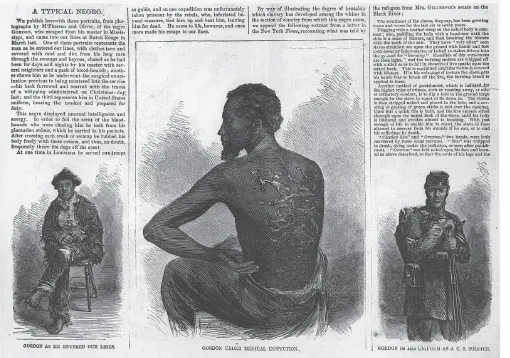

Figure 1.2. “Typical Negro,” Harper's Weekly, July 4, 1863. Much of the northern press was transfixed by a new American drama wherein the southern slave was transformed into a freedman, soldier, and citizen, as in the case of the Mississippi slave Gordon, shown here in his ragged clothes, displaying his whip-scarred back, and finally dressed in the Union uniform.

Ironically, both sides fought the Civil War in the name of freedom. “We all declare for liberty,” Lincoln observed in 1864, “but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing” To the North, freedom meant for “each man” to enjoy “the product of his labor”; to southern whites, it conveyed mastership—the power to do “as they please with other men, and the product of other men's labor.”5 The Union's triumph consolidated the northern understanding of freedom, with free labor at its center, as the national norm. In the process, the meaning of freedom and the identity of those entitled to enjoy its blessings were themselves transformed.

But more than redrawing the boundaries of citizenship, the Civil War linked the progress of freedom directly to the power of the national state. “It is war,” declared the nineteenth-century German historian Heinrich von Treitschke, “which turns a people into a nation.” Begun to preserve the old Union, the Civil War brought into being a new American nation-state. The mobilization of the Union's resources for modern war created what one Republican leader called “a new government,” with greatly expanded powers and responsibilities. Equally important, the war forged a new national self-consciousness. “Liberty,…true liberty,” Francis Lieber proclaimed, “requires a country.” This was the moral of one of the era's most popular works of fiction, Edward Everett Hale's short story “The Man Without a Country,” published in 1863. Hale's protagonist, Philip Nolan, in a fit of anger curses the land of his birth. As punishment, he is condemned to live on a ship, never to set foot on American soil or hear the name “the United States” spoken. He learns that to be deprived of national identity is to lose one's sense of self.6

The attack on Fort Sumter crystalized in northern minds the direct conflict between freedom and slavery that abolitionists had insisted on for decades. Before the war, many Americans, North and South, could speak with no sense of irony of their slaveholding republic as an empire of liberty. But the war, as Frederick Douglass recognized as early as 1862, merged “the cause of the slaves and the cause of the country.” To be sure, a generation of northern schoolchildren had learned to recite Daniel Webster's impassioned words spoken on the Senate floor in 1830: “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” But Webster was condemning the doctrine of states' rights, not the South's “peculiar institution.” When Douglass proclaimed that “Liberty and Union have become identical,” his target was chattel slavery—not simply a moral abomination, but an affront to national power. The master's undiluted sovereignty over his slaves, insisted Charles Sumner, the antislavery senator from Massachusetts, was incompatible with the “paramount rights of the national Government.”7 And the destruction of slavery—by presidential proclamation, legislation, and constitutional amendment—was a key act in the nation-building process. It announced the appearance of a new kind of national state, one powerful enough to eradicate the central institution of southern society and the country's largest concentration of wealth.

The scale of the Union's triumph and the sheer drama of emancipation fused nationalism, morality, and the language of freedom in an entirely new combination. Proponents of America's millennial mission interpreted the Civil War as a divine chastisement for this paramount national sin (a vocabulary the nonchurchgoing Lincoln himself adopted in his Second Inaugural Address). But with emancipation the war also offered an opportunity for national regeneration, as well as providing incontrovertible proof of the progressive nature and global significance of the country's historical development.

A “new nation” emerged from the war, declared Illinois representative Isaac N. Arnold, new because it was “wholly free.” Central to this vision was the antebellum principle of free labor, now further strengthened as a definition of the good society by the North's triumph. In the free-labor vision of a reconstructed South, emancipated blacks, enjoying the same opportunities for advancement as northern workers and motivated by the same quest for self-improvement, would labor more productively than slaves. Meanwhile, northern capital and migrants would energize the economy. Eventually the South would come to resemble the “free society” of the North, with public schools, small towns, and independent producers. Unified on the basis of free labor, proclaimed Carl Schurz, a refugee from the failed German revolution of 1848 who rose to become a leader of the Republican party, America would become “a republic, greater, more populous, freer, more prosperous, and more powerful, than any state” in history.8

The concrete reality of emancipation raised in the most direct possible form the question of the relationship between property rights and personal rights, between personal, political, and economic liberty. “What is freedom?” asked Representative James A. Garfield in 1865. “Is it the bare privilege of not being chained? If this is all, then freedom is a bitter mockery, a cruel delusion.”9 Did freedom mean simply the absence of slavery, or did it imply other rights for the emancipated slaves, and if so, which ones: civil equality, the suffrage, ownership of property? Here were the issues on which the turbulent politics of Reconstruction turned. And the political crisis that followed the Civil War compelled Republicans to define and extend the ideology they had brought out of the Civil War.

Most white southerners insisted that blacks must remain a dependent plantation work force in a laboring situation not very different from slavery. During Presidential Reconstruction—the period from 1865 to 1867 when Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, gave the white South a free hand in determining the contours of Reconstruction—southern state governments enforced this view of black freedom by enacting the notorious Black Codes, which denied blacks equality before the law and political rights and imposed on them mandatory year-long labor contracts, coercive apprenticeship regulations, and criminal penalties for breach of contract. Through these laws the South's white leadership sought to ensure that plantation agriculture and black subordination survived emancipation.10

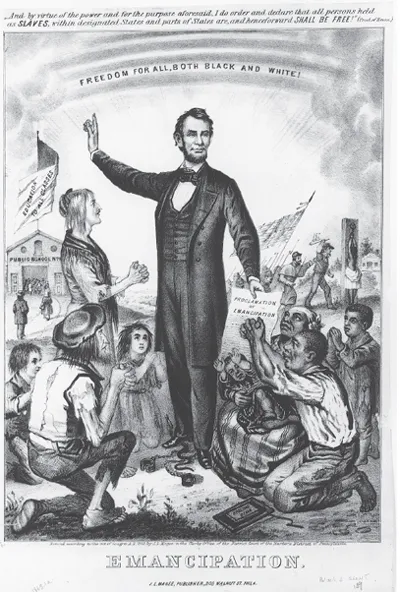

Figure 1.3. Emancipation, lithograph (Philadelphia: John L. Magee, 1865). Both the black slave and the southern poor white are elevated by emancipation in this Republican vision of a free labor America.

Thus the death of slavery did not automatically mean the birth of freedom. But the Black Codes so flagrantly violated free-labor principles that they invoked the wrath of the Republican North. Southern reluctance to accept the reality of emancipation resulted in a monumental struggle between President Andrew Johnson and the Republican Congress over the legacy of the Civil War. The result was the enactment of laws and constitutional amendments that redrew the boundaries of citizenship and expanded the definition of freedom for all Americans.

Johnson, a Unionist Democrat from Tennessee who had been added to the Republican ticket in 1864 to symbolize the party's desire to extend its reach into the South, was not only an accidental president but in many ways wholly unfit for that exalted office. An inveterate racist and believer in states' rights, he could not envision any federal action to protect the rights of the former slaves. At the other end of the political spectrum from Johnson stood the Radical Republicans, representatives within politics of ...