![]()

Chapter 1

Maintaining Their Ground

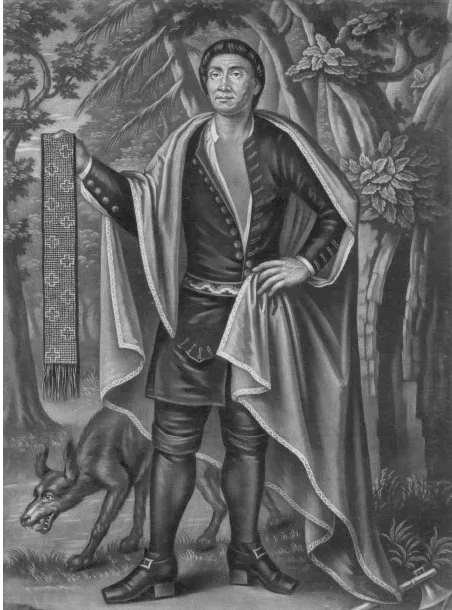

In the spring of 1710, after an arduous journey across the Atlantic Ocean, a middle-aged Mohawk man named Tejonihokarawa arrived in the bustling London metropolis. He was part of a delegation of “four Indian kings” brought to London by two prominent colonists (fig. 1).1 Treated as exotic dignitaries throughout their two-week stay, Tejonihokarawa and his peers enjoyed a bewildering array of sights. They held court with Queen Anne, sat for formal portraits, dined with dukes and admiralty, attended the theater, met with leading scientists and politicians, toured poorhouses and mental asylums, and attracted sizable crowds wherever they went.2 The absence of native written or oral testimony means that we are left to imagine how Tejonihokarawa experienced his trip. Very likely it reaffirmed a belief that friendship with the English was worth pursuing. Born around 1660, Tejonihokarawa had grown up accustomed to Europeans. A history of violent encounters with the French and their Indian allies encouraged Tejonihokarawa, like other Mohawks, to look to the English for security and military support. In 1701 he was one of a number of headmen who signed a deed assigning western hunting lands to the protection of the English Crown. By this time he had converted to Christianity and had begun preaching to other Indians to dissuade them from joining the French. In 1709 he recruited warriors for a joint English-Iroquois invasion of Canada. The invasion was aborted, but in 1710 he traveled to England with the other delegates to lobby the ministry for support of a second attempt. While in London he took the opportunity to request a missionary for his people, as well as agreeing to sell land to settlers on his return. By his actions Tejonihokarawa demonstrated his conviction that there were genuine advantages to be had by cultivating an alliance with the nascent English Empire.3

This brief glimpse of the life of one Mohawk Indian provides an alternative narrative to the older but still dominant story of the wholly destructive impact of colonization. The arrival of Europeans to North America wrought radical changes in the lives of the Haudenosaunee, but it did not signify their immediate or inevitable demise. Indians like Tejonihokarawa secured tangible benefits through forging relations with newcomers. In fact, despite a traumatic century of demographic loss through disease and warfare, the Iroquois emerged in the early eighteenth century as a viable force in North America. Still occupying their lands, controlling vital resources, and preserving their cultural autonomy, the Iroquois maintained their ground in both a literal and figurative sense. Having conquered and dispersed many western Indians, they widened their geographic orbit of influence and cemented a reputation among the English and non-Iroquois Indians alike as a martially powerful and politically unified people. In addition to important geographical and cultural resources, Iroquois success at withstanding the injurious forces of colonization owed much to the restricted nature of colonial and imperial incursions they encountered in New York. The early English Empire in New York was a limited empire in which trade, not territorial gain, served as the principal focus. Consequently, penetration of the interior, with Europeans’ subsequent demands on native lands, labor, and resources, occurred in a drawn-out, piecemeal fashion. Within this trading empire colonial officials generally preferred to keep the Iroquois at arm’s length. For men like Tejonihokarawa, courted and patronized in London, there was reason to feel hopeful in 1710. Although their world had altered dramatically by this date, it was still a world in which they exercised considerable mastery.

Figure 1. Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Emperour of the Six Nations, portrait by John Verelst (1710). William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. This portrait of Tejonihokarawa was made during his 1710 visit to London. The belt of wampum indicates his role as a man of diplomacy. The presence of a wolf marks his membership in the Wolf clan.

By the time the New York Iroquois first encountered Europeans, they had already undergone centuries of transformation. The Haudenosaunee embodied a rich and dynamic culture. Like most other native peoples, migration, warfare, ecological strain, and economic needs had been a mainstay of their existence, recontouring their material and cultural worlds. Historically they were part of a much larger linguistic group of Iroquoian-speaking Indians. By the 1500s they had located to lands south of the lower Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River, nestled between Schoharie Creek (near present-day Schenectady) in the east and the Genesee River in the west. Although distinguished by their separate abodes and distinct dialects, the original Five Nations of Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas were united under a cultural organization known as the Great League of Peace, probably formed sometime in the fifteenth century. They shared in common a complex set of cultural practices and values that governed relations between themselves and outsiders.4

Central to Iroquois culture was the concept of kinship, which provided the fundamental means for organizing society. The smallest kinship unit in Iroquoia was the “fireside family” comprising wife, husband, and children. Although this was a bilateral unit, it was largely submerged within the extended matrilineal household composed of mothers, daughters, sisters, and their male spouses and unmarried brothers and sons. Two or three maternal families—an ohwachira—lived together in a large bark-covered structure known as a longhouse. Each fireside family was allocated their own separate compartment complete with an individual hearth, but up to fifty people might live in a single longhouse, which could measure as much as forty-two meters in length. Collectively a group of maternal families made up a clan, distinguished by an animal insignia. Families from each of the three main clans— the Bear, Turtle, and Wolf—resided in most villages. Clan membership, a key element of individual identity, was traced through the mother’s line.

The kinship system contained rules governing relations between individuals, the most important of which was reciprocity. The mutual exchange of goods and services bound members of familial groups together. Most notably, clans served important reciprocal duties in the religious life that dominated villages by taking turns to condole and bury each other’s dead. Reciprocal ties also meant that individuals could expect food and lodging from members of the same clan residing in another village or nation. The clans were divided into two sets or sides, each responsible for performing duties for the other. The Great League of Peace drew its fifty hereditary chiefs from each of the clans precisely so that different clan chiefs could carry out symbolic functions for the other. But kinship and reciprocity did not always entail parity, and pre-contact Iroquoia was never strictly egalitarian. While reciprocity suggests a mutual give-and-take, in reality it served as a mechanism for creating hierarchy by generating a set of roles, duties, and expectations between individuals and groups. Resting on ideas about social obligation and mutual ties, kinship regulated economic practices, structured gender roles and relations, and provided the basis for group identity.

The Iroquois were a subsistence-oriented society based on farming, hunting, and small-scale trade. Land and its resources underpinned the Iroquois economy. The Iroquois cleared parcels of woodland to plant substantial crops of maize, beans, and squash, which formed the bulk of their diet. They supplemented this activity by hunting wild game and fowl and fishing in the numerous lakes and creeks. The Iroquois also gleaned the forested terrain for its natural harvest of nuts, fruits, and roots. They extracted maple syrup from trees and used timber for longhouses, canoes, tools, and firewood. As local resources diminished over time, communities relocated. The rich bounties of the natural environment ensured Iroquois economic autonomy.5

Despite the immense value of land to their way of life, the Iroquois disclaimed private ownership. Land was not an object or commodity that could be privately possessed, transferred through inheritance, or sold for profit. Land was a gift from their maker, the Great Spirit. The Iroquois still practiced an ownership of sorts, however, but it was one based on need, use, and occupation. Collectively, the Iroquois recognized the right of each nation to inhabit a specific region and respected each other’s hunting grounds and fishing camps. At a village level, although land was technically held in common, clan matrons determined what land was to be farmed and by whom. Allocation of land rights at the nation, village, and clan level served a practical purpose by ensuring fair and broad access. Even if an individual or family enjoyed special rights to a particular piece of land, they still had no right to sell it or give it away. The very fact that any Indian could assert a right to the land simply by making use of it guaranteed a substantial level of economic equality.6

“The Indian tribes have traded with each other from time immemorial,” missionary Joseph François Lafitau observed of the Iroquois in the early 1700s. Trade served a critical cultural function as a means to maintain alliances and promote relations of social and political obligation. Consequently, the exchange of goods frequently occurred within the context of diplomatic missions. Western Indians desiring to traverse through Seneca country used red pipestone as a diplomatic gift to ensure their safe passage. Families wishing to make amends for murder or injury sent diplomatic embassies loaded with presents to other communities. Iroquois practices make it extremely difficult to disentangle the political from the economic. Lafitau noted that “Their ways of engaging in trade is by an exchange of gifts. There are some gifts presented to the chief and others given wholesale to the body of the tribe with which they are trading.” Upon receipt of a gift, an individual or family was obliged to offer something in exchange. If a recipient disliked the gift he would return it and retrieve the original item. In this noncommercial form of exchange, the value of goods was not market dictated but “regulated only by the buyer’s evaluation and wants.” By giving and receiving, individuals, villages, and entire nations engaged in symbolic acts of alliance making. The Iroquois valued the act of exchange as much as the article they traded. The exchange of goods not only signified friendship but could also serve as an acknowledgment of unequal power relations. Tributary nations of the Iroquois in Pennsylvania acknowledged their social and political deference through their annual “gifts” of wampum, small marine shells of white or dark purple coloring.7

Small-scale trade satisfied basic material needs and wants by allowing villagers to obtain articles otherwise unavailable to them. Certain minerals and stones, such as jasper, white quartz, chalcedony, and red pipestone, used in the manufacture of arrowheads or believed to be endowed with spiritual energy and thus valued for their use in burial rites were obtained through trade with foreign Indians. Wampum beads were immensely valued because shell was thought to embody life-enhancing energy. Produced by coastal Algonquian Indians, wampum was only available via trade networks. Trade also occurred among the Five Nations: when one community had a surplus of goods they traded for something they lacked. Exchange took place within a bartering system in which individuals swapped one type of good for another.8

Labor was performed by all members of the community, but gender, age, and rank determined who performed what. Women tended crops, gathered wild produce, trapped small animals, performed household chores, and took care of children. Men hunted, fished, traded, and engaged in heavy village labor, such as clearing land and constructing homes. Children and the elderly performed labor that was age appropriate. The sexual and age division of labor was not unequal or hierarchical but complementary and reciprocal. Labor was performed through the extended lineage. Through appeals to consanguinity and marriage, kinship determined the division of labor and distribution of resources. Members of an ohwachira contributed to a household economy, sharing and swapping skills and goods. Familial ties ensured that each individual could expect to benefit from the labor of others at the same time that it placed an obligation on them to offer something in return. In this context, the value of sharing lay less in the resources shared than in the actual act of sharing: by its occurrence, it certified recurrence. Ties of mutuality united men and women, young and old, as each contributed valuable skills and resources to the village economy.9

Despite pervasive patterns of sharing and reciprocity, Iroquoia was not devoid of hierarchy. In fact, Iroquois society was a ranked society that comprised a social, political, and economic elite. Certain lineages that held titles for the hereditary League chieftains formed an elite stratum of society. The men who claimed these titles, the female heads of households who elected them, and their closest relations who acted as advisors formed the nobility known as agoïander.10 They enjoyed both social and political status. Jesuit missionaries who lived among the Iroquois in the seventeenth century frequently encountered people of “noble birth” “who managed the affairs of the country.” The social situation of the nobility stood in stark contrast to war captives held in servitude. One Seneca woman informed a Jesuit priest how her daughter’s noble ranking relieved her from performing domestic chores: “She was Mistress here and commanded more than twenty slaves … she knew not what it was to go to the forest to get wood, or to the River to draw water; she could not take upon herself the care of all that has to do with domestic duties.” But there were graduations even among the nobility, as Lafitau found that “although the chiefs appear to have equal authority … some of them preeminent over the others; and these are, as nearly as I can judge, either the one whose household [lineage] has founded the village, or the one whose clan is most numerous or the one who is ablest.”11

Paradoxically, the redistribution of wealth reinforced inequality based on kinship. The status of the hereditary chief and his family may have been derived from his affiliation to a particular lineage, but his influence depended greatly on his ability to dispense gifts among his followers. Early Europeans remarked that “The chiefs are generally the poorest among them, for instead of their receiving from the common people as among Christians, they are obliged to give to the mob.” However, their generous distribution of wealth was only possible because they enjoyed the greatest access to wealth. Principally this came in the form of prestige goods, items obtained through trade with foreign Indians and whose rarity enhanced their value. It was customary for diplomatic embassies and trade groups to bestow gifts on leaders as a mark of friendship or social deference. By redistributing these gifts to their followers, leaders solidified their power base and, ironically, improved their ability to attain more wealth. Lafitau remarked that gifts flowed in both directions, as hereditary chiefs not only played “a considerable role in feasts and community distributions” but were also “often given presents.” Yet gift-giving was not a purely benevolent act. Through gifting, leaders set up certain expectations of rights and duties by placing the recipient in a position of debt; the more gifts given, the greater the debt. As headmen augmented their status as leaders through dispensing their property they simultaneously augmented their right to obtain more wealth, thus perpetuating a cycle of giving and receiving. Through redistributive economics, social, political, and economic hierarchy was possible. Nonetheless, while pre-contact Iroquois society may not have been a haven of egalitarian relations, reciprocal duties of family members and the communal ownership of land and tools prevented extremes of inequality from developing.12

In the seventeenth century, a Dutch settler named Johannes Megapolensis was bemused to learn about the Iroquois origins myth. “They have a droll theory of the Creation,” he remarked, “for they think that a pregnant woman fell down from heaven, and that a tortoise … took this pregnant woman on its back, because every place was covered with water; and that the woman sat upon the tortoise, groped with her hands in the water, and scraped together some of the earth, whence it finally happened that the earth was raised above the water.” This woman was Sky Woman, a celestial being who resided in the Sky World, a physical realm that existed among the stars. While heavily pregnant she fell through a hole in the Sky World and descended through the clouds until she was caught on the back of a turtle. With the help of a muskrat, she covered the turtle’s back with soil, thus creating the North American continent. Sky Woman eventually gave birth to a daughter, known as Beloved Daughter or the Lynx. In time, Sky Woman and Beloved Daughter traveled all across the turtle’s back, exploring the country, naming creatures, and sowing seeds.13

The Iroquois origins myth reveals much about the role and high status assigned to women. The story positively emphasizes their crucial roles as life-givers and sustainers. The Iroquois believed themselves to be the common heirs of Sky Woman. In his investigation of Iroquois lore, Megapolensis noted that the Mohawk Turtle clan enjoyed the most status because “they boast that they are the oldest descendents of the woman before mentioned.” The second epoch of the creation story, which focuses on the relationship between Sky Woman and her daughter, and which was largely glossed over by nineteenth-century (male) anthropologists, lays the foundation of the matrilineal orientation of Iroquois society and highlights the significance attached to the mother-daughter relationship. Women derived much of their autonomy and power through the extended matrilineal household. Unlike men, who found themselves displaced after marriage between the homes of their wife and mother, women experienced the matrilineal household as a source of streng...