![]()

Chapter 1

Christians Mapping Jews: Cartography, Temporality, and the Typological Imaginary

It is the sorting out that makes the times, not the times that make the sorting.

—Bruno Latour

In a cogent essay critical of the ways in which “rationality” has become a mantra for dividing the pre-modern from the modern, Brian Stock has shown how the desire to push the boundaries of modernity either back to the Middle Ages, a modernizing tendency, or forward to later times, a medievalizing tendency, leaves untouched the multiple and syncopated linkages between rationality and its technologies—scientific instrumentation, textuality and subjectivity.1 Bruno Latour takes Stock’s critique even further, claiming that periodization itself is the problem of the modern.2 Using Boyle’s vacuum pump as an example, Latour shows how this “invention” can be considered as modern and revolutionary only if one starts periodizing—for example, by including certain events on a time line and excluding others (such as magic and religion) that would derail the invention’s teleology.3 Thus does Latour conclude that “time is not a general framework but a provisional result of the connection among entities.”4

In effect, Stock and Latour both work to derationalize rationality, thereby opening up possibilities for cultural studies of its technologies and drawing our attention, not to the question of power and rationality, but to the political power of rationality.5 How does “rationality” intervene to re-draw, to “re-cognize,” what counts as knowledge? Stock and Latour’s respective work is especially useful for interrogating medieval epistemologies, and has inspired my own interest in the tension between so-called traditional practices of medieval cartography—specifically, mappaemundi, the ubiquitous cartographic representation from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries—and purportedly rational and “modern” Ptolemaic cartographic practices, which became dominant in Western Europe in the fifteenth century and were notable for locating and representing objects in gridded space. The current textbook narrative of medieval cartography typifies this tension. Although such narratives are quite sophisticated and in fact eschew any notion of linear progression in medieval mapping, they nevertheless keep separate medieval mappaemundi from Ptolemaic maps: “whereas the didactic and symbolic mappaemundi served to present the faithful with moralized versions of Christian history from the Creation to the Last Judgment, Claudius Ptolemy’s instructions on how to compile a map of the known world were strictly practical.”6 Typically, the literature on medieval maps regards mappaemundi as encyclopedic, “unscientific,” whereas Ptolemaic cartography is considered a first step toward a “modern” practice. Mappaemundi get sorted out as “traditional” and Ptolemaic maps as “rational.” Supersession is at stake here.

This chapter attends to graphic details of these maps to tell a different story. Instead of sorting them out, it superimposes the “messy,” monster-infested, encyclopedic medieval mappaemundi on the gridded Ptolemaic maps. Indeed, as I show, the overlaps and misalignments of these two cartographic practices graph the Christian typological imaginary in ways that need to be better understood in medieval cartography in particular and medieval studies in general.7 To explain what is at stake in viewing the relationship between these cartographic practices as I do, I turn briefly to the work of anthropologist Johannes Fabian, who has studied early modern ethnography (a mapping practice in its own right) and its constructions of time and the other. Fabian claims that early modern ethnography came to deny what he calls the “coevalness,” or contemporaneity, of its encounter with the other. According to Fabian, such denial occurs when there is a “persistent and systematic tendency to place the referent(s) of anthropology in a Time other than the present of the producer of anthropological discourse.”8 In other words, rather than seeing itself as coeval with its referent, or part of the same time, anthropology tended instead to deny this coevalness and imagine itself as part of an allegedly more modern and rational time, and its referent part of a more primitive, irrational time.

Early modern ethnography did not, however, initiate such practices. When early Christians cut off Jews and their Hebrew scriptures from the “now” and placed them in a past superseded by the New Testament, they inaugurated the denial of coevalness. This chapter traces how the Christian typological imaginary extended itself to cartographic practices. Medieval maps helped to fabricate contemporary Jews as the first ethnographic “primitives,” since, as I shall show, medieval mapping practices denied coevalness to Jews, just as social scientists rendered primitive their anthropological “referents.” To rephrase Fabian and draw on the work of Jonathan Boyarin, there is a “persistent and systematic tendency” to place Jews in a time other than the supersessionary present of Christendom.

What follows is an attempt to delineate some of the ways medieval Christians used graphic technologies to inscribe supersession cartographically. Medieval maps became an important graphic surface for the Christian typological imaginary. Cartographic inscription was neither neutral nor insignificant, for, as we shall see, translating Jews from time into space was a way in which medieval Christians could colonize—by imagining that they exercised dominion over supersession.9 Although one of the goals of this chapter is to bring the typological imaginary of medieval mapping practices into view, medieval maps cannot be thought about in isolation, since the very notion of a map as an isolated stand-alone object is already an effect of modernist production of cartographic space. Both mappaemundi and Ptolemaic maps need to be studied as links in a chain of translations that graphically dispossessed medieval Jews of coevalness. This chapter, therefore, reads maps within a network of translations in order to discern their interacting imaginaries. The network includes diverse but relevant textual material, such as twelfth-century anti-Jewish polemic, fourteenth-century travel literature, and fifteenth-century Christian-Hebrew studies, as well as the instruments of translation, namely, astrolabes and alphabets.

The “Mother” of the Astrolabe: Dispossessing the Foreskin

I start with the dispossessions that take place in the most widely disseminated of medieval anti-Jewish polemics, Petrus Alfonsi’s Dialogue Against the Jews (1108–1110). In this Dialogue, Petrus Alfonsi, himself a converted Jew, educated in Arabic, learned in biblical Hebrew, an ambassador of Arabic science to France and England, disputes with his former Jewish self, which he enfolds in the persona of his interlocutor called Moses. He wields his Dialogue like a knife to excise this former self.10 His polemic is distinctive for deploying not only scientific arguments, but also, for the first time in this genre, scientific diagrams. He uses “science” to discredit talmudic knowledge for its irrationality.11 In the Dialogue’s longest scientific excursus, Alfonsi attacks the talmudic exegesis of Nehemiah 9: 6, “the hosts of heaven shall worship thee,” which locates the dwelling of God in the West. Only rabbinical ignorance of the concepts of time and longitude, according to Alfonsi, could allow such error to persist. After unveiling Moses’ ignorance, he then proceeds to teach him an astronomy lesson wherein he asserts the relativity of East and West, of dawn and sunset. Alfonsi’s astronomy lesson teaches the concept of longitude, whereby the contingent position of the observer using an astrolabe to take measurements determines relative timing and spacing. By marking such a difference between talmudic interpretation and the instrumentality of astronomy, Alfonsi implicitly constructs the rational observer as a Christian (male) and excludes Jews from this privileged position, the site of the one who knows. Alfonsi thus uses the “reason” of science in this excursus to deny his coevalness with Moses and to relegate him to a time other than the present of his scientific discourse. Science trumps or supersedes the Talmud.

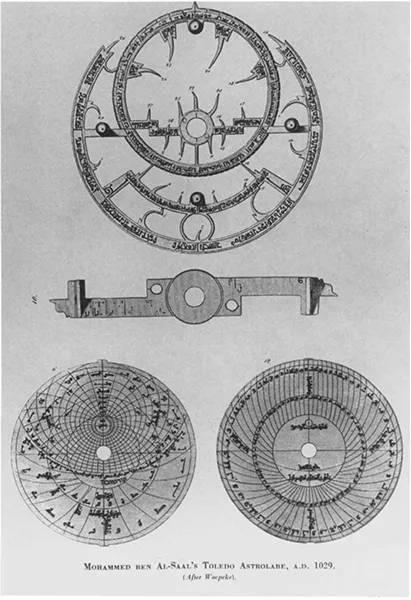

The astronomy lesson of the Dialogue drew on knowledge of the astrolabe.12 Astronomy texts and astrolabes dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries document Jewish and Arabic use of the astrolabe in Andalusian Spain.13 Of the six Andalusian astrolabes surviving from the eleventh century, one of the oldest, dated to 1029–30 from its inscription, has scratched on its surface the Hebrew equivalents for certain engraved Arabic star-names (Figure 3a, b). These graffiti attest to the cross-cultural use of this instrument. Scientific texts also indicate active Jewish participation in astronomical and astrological studies at Andalusian courts in the early twelfth century. A Toledan Jew, Abraham ibn Ezra, wrote eight noted treatises in astrology, among which is his treatise on the astrolabe (1146–48). The earliest set of astronomical tables in Hebrew, drawn up by Abraham Bar Hiyya in 1104, just predates the conversion of Petrus Alfonsi. The Dialogue thus misrepresents the actual technological expertise of contemporary Jews and in so doing dispossesses them of their own astrolabes as well as their scientific texts.14

Figure 3a. Andalusian astrolabe by Mohammed ben Al-Saal, 1029. As reproduced in Robert T. Gunther, The Eastern Astrolabes, vol. 1 of Astrolabes of the World, 3rd ed. (London: William Holland Press, 1972), no. 116.

This historical evidence for such close intertwining of Arabic and Jewish astronomical studies and instruments makes Alfonsi’s dispossession of Jews from astronomical discourse all the more stunning. Alfonsi stripped Jews of their coeval contribution to Andalusian astronomy and then infantilized and feminized their talmudic learning as the “verba jocantium in scholis puerorum, vel nentium in plateis mulierum” (“joking words of schoolboys and gossip of women in the streets”).15 Alfonsi could imagine the “universal” rational principles of the astrolabe as a means to purify him of his “pre-conversion”self, of the talmudic Jew, whom he abjects in the Dialogue. Since the astrolabe relativizes time by linking it to the circuits of the sun and stars, Petrus Alfonsi, with astrolabe in hand, need no longer remain incarnated temporally, ontologically, in that abject place from which Moses is said to come in the Dialogue. Alfonsi literally diagrams for himself a new place in the sun. The astrolabe thus becomes the instrumental means by which Alfonsi can both dispossess himself of his former Jewish self and through its possession ward off the shattering aspects of the dispossession he effects; in a word, the astrolabe is, for Alfonsi, a fetish.16

Figure 3b. Detail of the Hebrew equivalent of the engraved Arabic star names on Mohammed ben Al-Saal’s 1029 astrolabe.

Theological Telephones

At the very time Alfonsi was writing his anti-Jewish polemic, Christian biblical scholars of the Victorine school in Paris engaged local Jewish intellectuals in ways that Beryl Smalley and her students have thought of as cooperative, respectful, curious. Could it be that the Victorine interaction with local Jewish intellectuals fostered a sense of coevalness that might counteract Alfonsi’s denial to his Jewish interlocutor? These same Victorines knew Alfonsi’s Dialogue. In eight instances of the sixty-eight manuscripts in which the Dialogue was bound together with other texts, it traveled with Victorine texts. Two volumes of the Alfonsi text were also to be found in their Paris library. Thus the Victorines could consult local rabbis and read anti-Jewish polemic at the same time. To explore this paradox, I investigated the dissemination of cartographic interests among the Victorines. The early twelfth century marks a turning point for the production of mappaemundi. An important text, Imago mundi, written in 1110 by Honorius Augustodunensis, precipitated renewed interest in maps. His cosmography treated celestial and terrestrial geography, the measurement of time, and the six ages of universal history.17 Largely conservative and deeply derivative, its simplicity and clarity nevertheless guaranteed its wide circulation and broad influence. During the twelfth century Honorius’s text can be found traveling bound with Hugh of St. Victor’s De Arca Noe (1128–29) as well as with Petrus Alfonsi’s Dialogue Against the Jews. The library of St. Victor possessed two copies of this Imago mundi, and, when Hugh of St. Victor wrote his Descriptio mappe mundi in 1128 or 1129, he drew on Honorius’s treatise.

Victorines promoted the fabrication and study of maps. Kn...