![]()

Chapter 1

Reconquest, Holy War, and Crusade

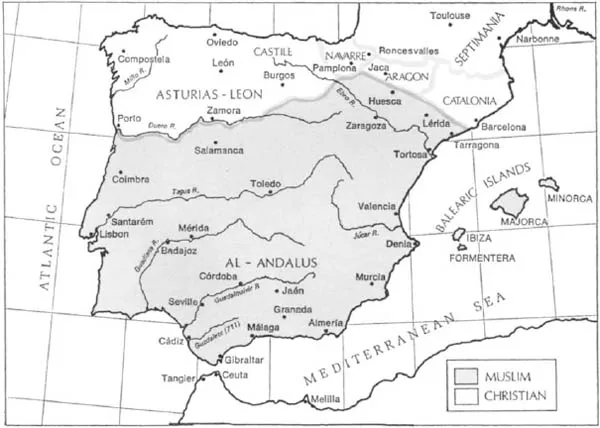

When the crusaders assaulted and captured Jerusalem in July 1099 the struggle between Christians and Muslims in Spain had been in progress for nearly four hundred years. From 711, when a mixed force of Arabs and Moroccan Berbers crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and overthrew the Visigothic kingdom, until the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba in 1031, Muslim supremacy in Spain was unquestioned. As the seat of Islamic power was Córdoba, an eccentric location in the southern part of the peninsula, the Muslims did not permanently occupy large stretches of mountainous zones in the north. That made it possible for small groups of Christians to form the tiny, independent states of Asturias, León, Castile, Navarre, Aragón, and Catalonia. Clinging to the Cantabrian and Pyrenees mountains, this congeries of Christian enclaves, variously ruled by kings or counts, was kept on the defensive for nearly three hundred years, as Muslim armies marched northward every summer to ravage their lands but never to conquer them. In those early centuries a no-man’s land stretching along the Duero River from the Atlantic to the borders of Aragón separated Christian and Muslim territory, but it was many years before the Christians dared to venture southward to occupy that zone (see Map 1). As the Christian population increased a gradual movement toward the Duero occurred and the process of settling that frontier zone commenced. In the northeast, however, Muslim rule reached as far north as the foothills of the Pyrenees until the late eleventh century.1

After the occupation of the Duero valley, the Christians took advantage of the breakup of the Caliphate to move into the Tagus valley, capturing Toledo in 1085. The invasions of the Almoravids (al-murābiṭūn) from Morocco soon afterward and of the Almohads (al-muwaḥḥidūn) in the middle of the twelfth century put the Christians on the defensive again, however, and temporarily checked their advance. Early in the thirteenth century victory over the Moroccans enabled the Christians to press forward to the Guadiana River and to capture the principal towns of the Guadalquivir valley. By mid-century all of Islamic Spain was in Christian hands except the tiny kingdom of Granada, and that was reduced to tributary status to Castile-León. Occupying the central meseta, the largest segment of the peninsula, the kingdom of Castile-León maintained a contiguous frontier with the Muslims until Ferdinand and Isabella conquered Granada in 1492. Meanwhile, the kingdoms of Portugal on the west and Aragón-Catalonia on the east had expanded as fully as possible by the middle of the thirteenth century, and their boundaries would remain fixed thereafter save for some minor adjustments. Thus in the closing centuries of the Middle Ages the conquest of Islamic lands remained the primary responsibility of the kings of Castile-León.2

Map 1. Muslim Spain, 711–1031.

The Reconquest: Evolution of an Idea

The preceding historical sketch summarizes a long period in the history of medieval Spain that Spanish historians have called the Reconquista. The reconquest has been depicted as a war to eject the Muslims, who were regarded as intruders wrongfully occupying territory that by right belonged to the Christians. Thus religious hostility was thought to provide the primary motivation for the struggle. In time, the kings of Asturias-León-Castile, as the self-proclaimed heirs of the Visigoths, came to believe that it was their responsibility to recover all the land that had once belonged to the Visigothic kingdom. Some historians assumed that that ideal of reconquest persisted without significant change throughout the Middle Ages until the final conquest of Granada and the inevitable union of Castile and Aragón under Ferdinand and Isabella.3

Nevertheless, in the last thirty years or so historians have challenged these assumptions, asking whether it is even appropriate to speak of reconquest. Did the reconquest really happen or was it merely a myth? If it is legitimate to speak of reconquest, then what exactly is meant by that term? Doubts about the validity of this idea are reflected, for example, in Jocelyn Hillgarth’s consistent placement of the word “Reconquest” in quotation marks.4 However that may be, Derek Lomax pointed out that the reconquest was not an artificial construct created by modern historians to render the history of medieval Spain intelligible, but rather “an ideal invented by Spanish Christians soon after 711” and developed in the ninth-century kingdom of Asturias. Echoing Lomax’s language, Peter Linehan remarked that “the myth of the Reconquest of Spain was invented” in the “880s or thereabouts.”5 Like all ideas, however, the reconquest was not a static concept brought to perfection in the ninth century, but rather one that evolved and was shaped by the influences of successive generations. In order to assess these views it is best first to trace the origins of the idea of the reconquest in the historiography of the early Middle Ages.

The Loss of Spain and the Recovery of Spain

The idea of the reconquest first found expression in the ninth-century chronicles written in the tiny northern kingdom of Asturias, the so-called Prophetic Chronicle, the Chronicle of Albelda, and the Chronicle of Alfonso III, which proposed to continue the History of the Gothic Kings of Isidore of Seville (d. 636).6 These texts, written in Latin no doubt by churchmen, have generally been associated with the royal court and probably reflect the views of the monarch and the ecclesiastical and secular elite. What ordinary people thought is unknown, but the chroniclers developed an ideology of reconquest that informed medieval Spanish historiography thereafter. The Chronicle of Alfonso III also served as the basis for subsequent continuations in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by Sampiro, bishop of Astorga (d. 1041), Bishop Pelayo of Oviedo (d. 1129), and the anonymous author of the Chronicle of Silos.7

The history of the idea of the reconquest may be said to begin with the collapse of the Visigothic Monarchia Hispaniae of which Isidore of Seville spoke. From their seat at Toledo, the Visigoths were believed to have extended their rule over the whole of Spain, including Mauritania in North Africa, in other words over the whole Roman diocese of Spain.8 Given the interest of medieval and early modern Spaniards in the possibility of conquering Morocco, it is well to remember that they knew that Mauritania or Tingitana was anciently one of the six provinces of the diocese of Spain.9 In the early fourteenth century Alfonso XI of Castile (1312–50), repeating the language of the canonist Álvaro Pelayo, laid claim to the Canary Islands because, as part of Africa, the Islands were said to have once been subject to Gothic dominion. In the fifteenth century Alfonso de Cartagena made much the same argument.10 The concept of a unified and indivisible kingdom embracing the entire Iberian peninsula, though it hardly corresponded to reality, was one of the most significant elements in the Visigothic legacy. That idea was reflected in the thirteenth-century account of Infante Sanchos protest against the plans of his father, Fernando I (1035–65), king of León-Castile, to partition his dominions among his sons: “In ancient times the Goths agreed among themselves that the empire of Spain should never be divided but that all of it should always be under one lord.”11

The Muslim rout of King Rodrigo (710–711), the “last of the Goths,” at the Guadalete river, on 19 July 711, brought the Visigothic kingdom crashing to the ground and changed the course of Spanish history in a radical way. The contemporary Christian Chronicle of 754, written in Islamic Spain, deplored the reign of King Rodrigo, “who lost both his kingdom and the fatherland through wicked rivalries.” Decrying the disaster that befell the Visigoths, the chronicler lamented that “human nature cannot ever tell all the ruin of Spain and its many and great evils.”12 The Prophetic Chronicle declared that “through fear and iron all the pride of the Gothic people perished . . . and as a consequence of sin Spain was ruined.” In varying degrees the ninth-century Asturian chroniclers mourned the loss or extermination of the Gothic kingdom, the ruin of Spain, and the destruction of the fatherland. Similar language appears in the chronicles of later centuries.13

By contrast with the catastrophic loss of Spain, the chroniclers tell us that through Divine Providence liberty was restored to the Christian people and the Asturian kingdom was brought into being. This reportedly occurred when the majority of the Goths of royal blood came to Asturias and elected as king Pelayo (719–737), son of Duke Fáfila, also of the royal line. Pelayo, formerly a spatarius or military officer in the Visigothic court, supposedly was King Rodrigo’s grandnephew. When faced with an overwhelming Muslim force demanding that he surrender, Pelayo, in the chronicler’s words, responded:

I will not associate with the Arabs in friendship nor will I submit to their authority . . . for we confide in the mercy of the Lord that from this little hill that you see the salvation of Spain (salus Spanie) and of the army of the Gothic people will be restored. . . . Hence we spurn this multitude of pagans and do not fear [them].

The ensuing battle of Covadonga, fought probably on 28 May 722, was a great victory for Pelayo, for “thus liberty was restored to the Christian people . . . and by Divine Providence the kingdom of Asturias was brought forth.”14 Among the Asturians the battle of Covadonga became the symbol of Christian resistance to Islam and a source of inspiration to those who, in words attributed to Pelayo, would achieve the salus Spanie, the salvation of Spain.

The inevitability and the inexorability of the struggle that Pelayo commenced was stressed by the Chronicle of Albelda, which declared that “the Christians are waging war with them [the Muslims] by day and by night and contend with them daily until divine predestination commands that they be driven cruelly thence. Amen!” Recording the prophecy that the Muslims would conquer Spain, the Prophetic Chronicle expressed the hope that “Divine Clemency may expel the aforesaid [the Muslims] from our provinces beyond the sea and grant possession of their kingdom to the faithful of Christ in perpetuity. Amen.!”15

Identifying the Goths with Gog and the Arabs with Ishmael, the author of the Prophetic Chronicle offered this reflection on the words of the Prophet Ezekiel (Ezek. 38–39) addressed to Ishmael: “Because you abandoned the Lord, I will also abandon you and deliver you into the hand of Gog . . . and he will do to you as you did to him for one hundred and seventy times [years].” Although the Goths were punished for their crimes by the Muslim invasion, the chronicler proclaimed that “Christ is our hope that upon the completion in the near future of one hundred and seventy years from their entrance into Spain the enemy will be annihilated and the peace of Christ will be restored to the holy church.” Calculating that those one hundred and seventy years would be reached in 884, the author predicted that “in the very near future our glorious prince, lord Alfonso, will reign in all of Spain.”16 Aware of Alfonso III’s (866–910) recent successes against the Muslims, as well as internal disorders afflicting Islamic Spain, the chronicler was confident that the days of Muslim domination were numbered. This anticipation of the imminent destruction of Islam proved illusory, but the hope persisted for centuries.

The notion of continuity existing between the new kingdom of Asturias and the old Visigothic kingdom, whether actual or imagined, had a major influence on subsequent development of the idea of reconquest. The ninth-century chroniclers were at pains to establish the connection between the old and new monarchies, identifying the people of Asturias with the Goths, and linking the Asturian kings to the Visigothic royal family. Indeed, the chroniclers consciously conceived of themselves as continuing Isidore’s Gothic History. According to the Chronicle of Albelda, Alfonso II (791–842) “established in Oviedo both in the church and in the palace everything and the entire order of the Goths as it had been in Toledo.”17 Exactly what that meant is not entirely certain, but the purpose of the statement was to affirm the link between Asturias and the Visigothic kingdom, however tenuous that might be.

The Gothic connection thus established was repeated again and again in subsequent centuries, though without any further attempt at proof. For example, the twelfth-century author of the Chronicle of Silos described Alfonso VI, king of León-Castile (1065–1109) as “born of illustrious Gothic lineage.” Two centuries later, Álvaro Pelayo recalled that Alfonso XI was descended from the Goths. When Enrique of Trastámara claimed the throne in opposition to his half-brother Pedro the Cruel (1350–69), he declared that “the Goths from whom we are descended” chose as king “the one whom they believed could best govern them.”18 Fifteenth-century expressions of this sort were commonplace, and even Ferdinand and Isabella were reminded of their Gothic ancestry. By asserting, though not demonstrating, the bond between the medieval kings and their supposed Visigothic forebears, the chroniclers also underscored the close link between the Visigothic monarchy and its purported successor in Asturias-León-Castile. In doing so they justified the right of the medieval kings, as heirs of the Visigoths and of all their power and authority, to reconquer Visigothic territory and restore the Visigothic monarchy.19

The emergence of the kingdoms of Portugal and Aragón-Catalonia in the twelfth century, and to a lesser extent, of Navarre, necessitated some readjustment in Castilian thinking as it became apparent that the eastern and western monarchies would also have their share of the old Visigothic realm. In expectation of the inevitability of conquest, the kings of Castile, León, and Aragón optimistically made several treaties that will be discussed in later chapters, partitioning Islamic Spain. Even more optimistically the kings of Castile and Aragón concluded a treaty in 1291 providing for the partition of North Africa, allotting to Castile Morocco—ancient Mauritania—over which the Visigoths reportedly had once held...