![]()

1

THE CONCEPT OF ARTIFICATION

ELLEN DISSANAYAKE

THE ANCIENT MARKINGS found on boulders, cliff walls, and in caves are usually referred to as “rock” (or “rupestrian” or “parietal”) art. But what does “art” mean in this context—or indeed in any other? If the term is examined carefully, it reveals a landmine of irrelevant and confusing assumptions. As recently as the nineteenth century, the term “art” could be applied to almost anything. It meant skill, in the sense of fully understanding the principles involved in an endeavor—such as the art of Japanese cooking, the art of boat-building, or—today—even the “art” of medical diagnosis or psychotherapy. While skill is involved in all these disciplines, it is evident that the term “art” also implies that even scientifically based fields make use of intuitive, emotional, and nonrational expertise.

In addition to skill and intuition, other qualities and characteristics pervade ideas about art today:

•artifice (something contrived, “artificial” rather than natural, imitative rather than the real thing)

•beauty and pleasure (admiration and enjoyment)

•the sensual quality of things (color, shape, sound)

•the immediate fullness of sense experience (as contrasted with habituated, unregarded experience)

•order or harmony (shaping, pattern-making, achieving unity or wholeness)

•innovation (exploration, originality, creativity, invention, seeing things a new way, surprise)

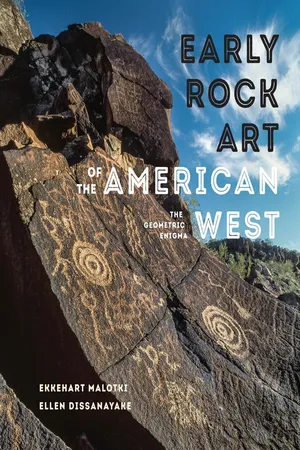

1.1 Cluster of deeply carved dotted and concentric circles, Oregon

•adornment (decoration, display)

•self-expression (presenting one’s personal view of the world)

•a special kind of communication (conveying information in a special kind of language; symbolizing)

•nonutilitarian (made for its own sake, having no function)

•serious and important concerns (significance, meaning)

•make-believe (fantasy, play, wish-fulfillment, illusion, imagination)

•heightened existence (exalted emotion, ecstasy, self-transcendence)

Which of these meanings or connotations are included in our notions of rock art? Philosopher Denis Dutton has offered a “cluster” definition of art considered as a universal cross-cultural category.1 He lists twelve characteristics, most or all of which he claims will be found in artifacts and performances that are typically called art. Dutton’s list includes features of works of art themselves as well as qualities of the experience of art. These are:

•giving direct pleasure

•skill and virtuosity

•style

•novelty and creativity

•a critical language of judgment and appreciation

•representation

•a special focus or bracketing-off from ordinary life

•expressive individuality

•emotional saturation

•intellectual challenge

•art traditions and institutions

•imaginative experience

Dutton’s characteristics are the result of serious and careful thought, and are worthy of consideration. However, each can be applied to obvious non-art (which Dutton admits), and scholars of rock art will question the applicability of at least some of these, such as pleasure, novelty, representation, individuality, emotional expression, or intellectual challenge in many or all of the markings that they see or study.

Because of all the baggage this tiny word carries, it is not surprising that most archaeologists who study ancient marks on rocks make a great effort to avoid the term “art” altogether. To them it smacks too much of aestheticism and subjective judgment, connotations that, in their eyes, ultimately render the field of parietal art studies “unscientific.” To remedy the stigma, they offer instead substitute terms ranging from simple “pictures” or “images” to such esoteric appellations as “ideomorphs,” “graphemes,” or “symbolic graphisms.” Some scholars point out that the word “art” can be used neutrally (as in “child art” or “chimpanzee art,” and by extension, “rock art”) rather than evaluatively (as in “X is a work of art”). But even this distinction seems useless: Why not just say “scribbles” or “paintings” or “carvings” or some other descriptive term and avoid the problematic connotations of the word art?

1.2 Time-worn cup-and-ring motif, Arizona

SHIFTING FOCUS FROM NOUN TO VERB

The term “rock art” thus requires a qualification—that “art” be considered as an abbreviation, as it were, of the abstract noun “artification,” from the newly coined verb artify. This reconceptualization considers rock markings not as things—objects, images, or works that can be called art—but as the outcome of an activity. This completely new way of thinking about art requires what might be called a Copernican shift in one’s approach to aesthetic matters. Unlike the modern Western concept of art with its elite idea of beaux arts or fine arts, artification emphasizes the act of making, not the result—an activity that will be described more precisely in the following discussion.

In this book, the act, not the product, of artifying applies to every instance of what is today called rock art. By conceptualizing art(ifying) as a verb, I think we come closer to most languages in the world, which have verbs for individual activities such as drawing, painting, carving, singing, dancing, and so forth but do not have a noun that refers to these activities as all belonging to a super-category.

Artification refers to what people do when they make images, engravings, paintings, and so forth. It is a behavior or process that allows us to understand rock markings as the result or residue of an activity that—like language and toolmaking—evolved over millennia to help our ancestors adapt to their ways of life as foragers (a term that we use interchangeably with “hunter-gatherers”). Artification is not a method for identifying or interpreting individual marks or styles, which is another, different, matter—one we do not address here.

The concept of artification provides a broader scope and firmer basis for treating the art-like endowments (like dancing, singing, mark-making, etc.) of our species than does the tangled mix of meanings that the concept of art has acquired over the centuries. Questions such as “What is art?” or “Is rock art ‘art’?” can be phrased in other ways: “What do people do when they make art?” “Is this an instance of artification?” In using a verb rather than a noun, the emphasis shifts from labeling the artifact to describing the behavior.

It is essential to understand that the word artification is not a synonym for art or art-making. As used here, the concept of artification rests on the capacity of human beings to make ordinary everyday experience (or “ordinary reality”) “extra-ordinary” or special. Although artifying is something that all people, even children, do, it has been overlooked (or underappreciated) by scholars who identify distinctive characteristics of our species. As mentioned in the Introduction, neither the word “art” nor the activity of making art is found in Donald Brown’s list of human universals. Decoration, dance, music, and poetry are represented there, even though they are, like art, categories of things whose precise nature is not always easy to identify cross-culturally. Like rock markings, they are the results of the broader, universal capacity, not shown by any other animal, of artification.

1.3 Complex palimpsest of abstract-geometrics, Nevada

The concept of artification arises from the observation that humans everywhere, unlike other animals as far as we know, differentiate between an order, realm, mood, or state of being that is mundane, ordinary, or “natural,” and one that is unusual, extraordinary, even “supernatural.” Virtually every ethnographic account of a premodern society anywhere in the world suggests or states outright this distinction. In Native American cultures, for a few examples, anthropologists Dennis and Barbara Tedlock specifically cite Hopi ‘a’ne himu (sic), Sioux Wakan, Ojibwa manitu, and Iroquois orende; they additionally mention “other worlds” of Tewa, Zuni, Wintu, and Papago.2 Some scholars have argued that in many aboriginal and other small-scale societies, the two realms of ordinary and extraordinary interpenetrate and may have done so in the worldviews of our early ancestors.3 This argument is well taken. However, even in the technologically simpler groups that ethnographers have described, people employ special practices that access a supernatural realm, indicating that there is a distinction in thought and behavior between quenching one’s thirst and imbibing a ritual drink, or between walking around in the forest and dancing in thanks to the forest. In these cases, ordinary behavior is altered, made special, artified.

1.4 Ancient abstracts, some “rejuvenated,” Arizona

Artification is not the same thing as cultural transformations of nature. Humans, for example, take raw food and transform it for their use by cooking it. Similarly, they take other materials from nature—fiber, stone, wood, bone, clay, animal skin—and make shelters, tools, utensils, weapons, clothing, and the various other things needed for their lives, such as hand axes from flint or microchips from silicon. Herbert Cole, an American historian of African art, has memorably utilized Claude Lévi-Strauss’s famous title, The Raw and the Cooked, by speaking of the raw, the cooked, and the gourmet. Artification can be likened to Cole’s addendum. For, in addition to transforming nature by means of culture, humans at some point in their evolution apparently felt that in some circumstances such merely utilitarian transformations were not sufficient. They additionally made their shelters, tools, utensils, weapons, clothing, bodies, surroundings, and other paraphernalia extraordinary or special by shaping and embellishing them beyond their ordinary functional appearance. They “artified” these things, typically when the items or the occasions for their use were considered important.

When did humans begin to artify? Before developing a capacity to make an ordinary thing into something extraordinary, they had to first recognize the extraordinary. Of cours...