![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

On the 28th July 1902, 1,000 Indian troops arrived in the city of Liverpool on a steamship from Bombay. They were en route to London to take part in the Coronation celebrations of Edward VII. The City Corporation took advantage of their presence to organise a parade through the city centre and to host a civic reception that evening at St. George’s Hall, the newly-built showpiece declaring Liverpool’s status as the second city of the British Empire and displaying the grandeur of the new municipality. The Indian troops took their seats in orderly and disciplined rows dressed in the splendour of their regiments. The hall was packed with civic dignitaries, members of the public who had managed to obtain seats and representatives of the press. An Englishman entered, dressed in the traditional robes and turban of an Ottoman ‘alim. Five hundred of the soldiers stood and shouted, ‘Allahu Akbar’. As the takbir resounded around this most English of venues, the man took his seat amongst the official guests. One of the many remarkable things about this incident is that the Indian Muslim sepoys knew exactly who had entered the hall, and were prepared to break ranks to show their respect.1 An extraordinary life lies behind this one incident, and there are many significant reasons why this should be told, particularly at a time when Muslims in Britain experience considerable challenges concerning their loyalty, identity and citizenship, and when the survival of the British brand of multiculturalism is itself under pressure.

At a time when the British Empire was at its zenith and very few Muslim nations remained free from European domination, one man took it upon himself to promote Islam in the heart of history’s greatest colonial enterprise. Fully believing in the truth of the revelation that the Prophet Muhammad received and passionate in his conviction that Islam, a religion that he described as being fully conversant with reason, he succeeded in converting more than 500 British men and women to Islam. For a period of fifteen years, he was rarely out of the media in Liverpool, the Isle of Man, the northwest of England and even nationally and internationally.

On the 29th July 1893, the Manchester Clarion reported (in the terminology of the day) that a ‘Muhammaden’ mission in Liverpool was making converts amongst educated Englishmen. The article described a movement called the Liverpool Muslim Institute, and seemed to be astonished at the idea that a mosque should open every day for prayers in a busy English seaport. The reporter was surprised ‘at the turning of the tables’, the idea that the East was actually engaged in trying to convert the West. He stated that the honorary secretary distributed explanatory works on Islam and that tracts are scattered about on the premises, ‘sowing the seeds of a new religion in the conventional missionary manner, which we, for other use, invented.’2

The missionary theme also appeared in an otherwise informative article that was printed in the Sunday Telegraph three years later. The article deserves to be set out in full and will be used to introduce readers to the subject of this biography. The article appeared under the headline, ‘A Mosque in Liverpool where Britons pray to Allah’, and read as follows:

Here in England there is a Muslim community – British born subjects of the Queen as white as we are, English-speaking yet Mussulmans. They have a Sheikh, a mosque, a college and even a weekly newspaper to advance their interests. Liverpool is the centre of Muhammadenism in England – indeed in the British Isles. It only dates back to the Jubilee year of 1887. In that year a Liverpool solicitor decided to embrace what he regarded as the true faith. This was Mr W.H. Quilliam, a gentlemen much respected in Liverpool. He is an archaeologist, and a man of learning – the bearer of a well-known name on the Mersey and in the Isle of Man, and as an advocate, one of the most familiar figures in the police and judicial courts of Liverpool … last year there were 24 converts, making 182 who, since 1887, have renounced Christianity or Judaism. Moreover, Mr Quilliam as a recognition of his devotion to his new religion, was appointed by the Sultan of Turkey, who is the Caliph of the Faithful outside India, as the head of the movement in England. His title in this capacity is the Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles. It is a peculiar sight to see elderly Englishmen bowing toward Mecca and repeating the well-known formula, the base of Islam, ‘la ilah illalah. Muhammad rasul Allah’. They have even begun to send out English Muhammaden missionaries to West Africa to advance the cause of the Crescent against the Cross.3

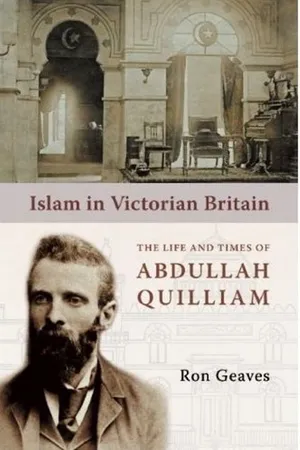

William H. Quilliam (1856-1932) was a well-known Liverpool solicitor who converted to Islam after visiting Morocco in 1887. He formally announced his conversion to Islam in 1888 and changed his name to Abdullah. The Liverpool Muslim Institute and British Muslim Association, which he founded to promote Islam in Britain, opened in September 1887, two years before the Woking Mosque was built outside London; although there may be a dispute about the first building to be used by Muslims in Britain as a place of prayer, there is no doubt that the first attempt to promote Islam publicly from within a mosque and an Islamic centre in Britain took place in Liverpool over the following twenty years.

The British media were not always supportive of Quilliam’s efforts, especially in times when patriotic jingoism flared during military campaigns against a Muslim territory or when Muslims rebelled against their colonial masters. The Porcupine, a well-known satirical magazine in Liverpool, depicted Abdullah Quilliam with a note of humorous derision, caricaturing him dressed in his Ottoman robes, turban and fez and riding a white stallion through the streets of Liverpool with a monkey on his shoulder, whilst the poverty-stricken women of the city’s slums threw flowers at his feet. However, they did remain relatively respectful, as did most of the city’s newspapers. After all, Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam, the eccentric Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles, was also William Quilliam, a Victorian gentlemen, property owner and well-known lawyer who mixed throughout his life with the gentry and with public figures from the city’s commercial, legal and political elites.

It is worth taking a closer look at The Porcupine’s depiction of Abdullah Quilliam, for even today I have met Muslims in the city of Liverpool who take the caricature literally. Behind the attempt to present Quilliam as a harmless but deluded eccentric – a charismatic ‘trickster’ leading the gullible public astray, quixotically astride his white steed – lay some truths about the man which question the cartoon’s representation. The white stallion had been presented to Abdullah Quilliam’s eldest son by Abdul Hamid II (r.1876-1909), the ruler of the Ottoman lands and Sultan of the last great Muslim empire (the horse had been shipped to Liverpool from Constantinople). The family had named the horse Abdullah and it was a much-loved family pet. Whether Quilliam ever rode his son’s horse through the streets of Liverpool is not recorded. Likewise, the portrayal of the monkey on William Quilliam’s shoulder was probably suggested to the cartoonist by the Sheikh’s considerable interest in zoology. Like many Victorian gentlemen of independent means, Quilliam was a dilettante; he had a powerful and inquiring mind that sought knowledge of the world around him. He maintained both a private zoo and a museum of oriental artefacts. Muslims from around the globe would send him specimens to enhance both of these collections.

It is unlikely that the women of Liverpool’s slums ever threw flowers at his feet, but some of them may have been inclined to do so. Quilliam was a philanthropist with a strong sense of the injustices suffered by the Victorian poor. He often used his considerable financial and legal resources to track down wayward husbands and ensure that their wages went to feed their hungry children.

It is extremely doubtful that Abdullah Quilliam, Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles, would ever have worn his tarboosh and turban in the streets of Liverpool. Quilliam believed passionately that Islam was a universal religion that required no special dress and had no clerical class. His robes were a marker of his official position, given to him by the Sultan whom he regarded as the spiritual leader of all Muslims, the Caliph of Sunni Islam, and to whom he owed fealty. However, apart from official functions, or when leading jumu‘a prayers at the mosque and officiating at Muslim funerals or weddings, when he did wear his robes, he usually wore the everyday dress of the Victorian gentleman of his class. He would no more have worn his lawyer’s robes in the street as his formal Islamic dress.

However, the depictions of Quilliam in the media beg some serious questions that this book will seek to illuminate. Why would the Caliph of Islam send a valuable stallion to Liverpool as a gift for a Liverpudlian lawyer, even one who had converted to Islam? Why would both the Sultan of the Ottomans and the Amir of Afghanistan confer upon a British convert to Islam the title of Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles? How did this man’s reputation reach Muslims around the globe to such a degree that they not only corresponded regularly with him, but even sent him gifts for his pastimes? And finally, what kind of man took care of the poor, the orphans and the distressed of the wider community in Liverpool, and to what degree did he see these activities as the duty of the faithful Muslim?

This is an appropriate time for a biography of Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam. A study of his small Muslim community in Liverpool not only provides scholars with further knowledge of the Muslim presence in Britain during the nineteenth century, but it is also highly relevant to the issues of Muslims living in non-Muslim western societies in the twenty-first century. In recent years, Quilliam has already begun to attract the attention of many British-born Muslims of migrant descent, who see him as an iconic figure: a native-born Englishmen who converted to the true faith along with many others, and whose presence in the country was neither as an economic migrant nor as a refugee fleeing persecution or war. Quilliam was a British citizen by birth, and a Muslim by conviction. Consequently he is of interest to contemporary converts to the faith. Some have picked up on Quilliam’s Britishness to represent him as the ideal of an integrated and moderate Muslim, able to provide an exemplary bulwark against extremism. The Quilliam Foundation, founded in London in 2008, has adopted his name in just such a manner; whilst in Liverpool, the sterling efforts of the Abdullah Quilliam Society are aimed at purchasing the buildings of his mosque and centre in order to return them to their former glories.

But care needs to be taken with Quilliam. He was not necessarily the friend of British governments, and his faith came first and foremost in his loyalties. When there were conflicts of conscience between loyalty to the laws of men and the law of God, Quilliam had no doubt where his allegiance lay. This study of his life provides insights into the challenges of being both a devout Muslim and a citizen in a non-Muslim nation.

Abdullah Quilliam was a Victorian gentlemen and a native-born Liverpudlian deeply located in his time and place. According to his own estimates, and supported to some degree by the records of conversion that he published each week in The Crescent, he successfully converted over 500 British men and women to Islam. He had his own strategies for undertaking da‘wa (promotion of Islam), and these deserve to be examined in the light of contemporary debates in Muslim communities concerning proselytising non-Muslims. This is of interest both to British Muslims and also to scholars of religion who are interested in conversion. The majority of Quilliam’s converts were practising Christians. What does this tell us about the condition of Christianity in the nineteenth century? Were the circumstances of their conversion only applicable locally in Liverpool and its surrounds?

Finally, Quilliam is of contemporary significance because he was an ‘alim, a leader of a Muslim community in a large urban environment that was rapidly transforming into a multicultural city. There is a great deal of controversy today about the role of the imam in non-Muslim societies and about Muslim leadership in general. These debates are highly politicised, and the research undertaken by academics in this context will not merely add to scholarly knowledge, but will also help to form government policies. Can anything be learned from this nineteenth century British ‘alim that may be useful in helping policy-makers and Muslims improve the quality of Muslim leadership in the diaspora communities of today?

Phillip Waller warns us that anthropomorphizing a city is not an acceptable method of historical writing;4 but it has to be acknowledged that the city of Liverpool is a central character in the book. The life of Abdullah Quilliam must be viewed in its setting. Although the family originated in the Isle of Man, Quilliam was a Liverpudlian lawyer, and he was born, partly educated and later worked in the city of Liverpool. The mosque could only have flourished in the way that it did in a very small group of British cities, and Liverpool was one of these. John Belchem describes Liverpool as the ‘shock city’ of post-industrial Britain.5 The city where Quilliam was born in the mid-nineteenth century was already experiencing massive growth, and during his lifetime this expansion would continue unabated. Even by the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Liverpool was described as ‘the first town in the kingdom in point of size and commercial importance, the metropolis excepted’.6 Although not one of the new Northern industrial centres like nearby Manchester, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Liverpool rapidly became the heart of the Transatlantic trade, the link between Britain and Ireland and, after the invention of the steamship, the fulcrum between industrializing Britain and the rest of the world, especially India and Africa.7

From a population of 7000 in 1708, by the time that Quilliam was born in 1856 the population of Liverpool had expanded to 376,000. 80% of this population increase was due to migration. The wealth of the city was in commerce, and the docks were the hub of Liverpool’s activity. The tonnage of shipping had grown alongside the population, from 14,600 in 1709 to 4,000,000 in 1855. In order to cope with the burgeoning trade, the docks increased exponentially: seven new docks had been built in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but this was before the period of Victorian expansion that oversaw the building of the most magnificent dock architecture in Britain.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the annual value of exports was £55,000,000, accounting for half the exports of the nation. The influx of wealth and human capital resulted in a massive disparity of wealth between the commercial elite and the city’s poor, who were mostly dependent on casual dock labour. Consequently, Power is able to say that the city was ‘moulded by the powerful forces of international trade, mass migration and appalling public health’.8

Migration also brought to the city unique sectarian problems. The majority of Liverpool’s migrants were from northern and southern Ireland, Wales and Scotland. They brought with them their own forms of religious life, predominately rival Nonconformist movements and Roman Catholicism. The Irish in particular maintained strong sectarianism, and the presence of Ulstermen in Liverpool brought Orangeism, which would lead to sectarian violence. In addition, the Irish formed the bottom of Liverpool’s occupational, social and residential hierarchies and became subject to sectarian abuse. ‘No popery’ was incorporated into the Tory-Anglican establishment of the city, and some Protestants were prepared to take to the streets to campaign against the perceived empty ritualism of the established Anglican Church. Street rioting was both a symptom of this sectarian strife and a result of temporary breakdowns of social order often caused by abject poverty fuelled by alcohol abuse. The city authorities left the Protestant and Catholic populations to defend their own borders and to discipline themselves, thus forming ghettoized spatial territories demarcated by religious, political and cultural beliefs. Only the city centre was guarded by the authorities in order to prevent riot and disorder. Sectarian rioting remained the characteristic protest in Liverpool until the transport strike of 1911. In 1919, the city experienced its first taste of race riots that moved beyond the Irish to other communities, and skin colour became a factor.9

The second city of the Empire was thus marked by severe polarities between wealth and poverty, contained some of the best architecture in the land yet had terrible sanitation problems, and suffered bitter religious conflict, inter-ethnic difficulties and fluctuations of employment caused by the over-dependence on casual labour in the docks. It is not surprising that Charles Dickens visited the city in order to do research for his novels. Migration had brought with it cheap and sweated labour, which was served by a large secondary street economy made up of hawkers and beggars, lodging-house keepers, bookmakers and their touts, pawnbrokers and prostitutes.

This is the scene that would have met the increasing number of recruits to the British merchant fleet from around the world. They were predominantly young men and often Muslim. Kept at a distance from the wealthy middle-class areas in the city, they inhabited areas that the unwary would not enter. The collection of wealth was the main occupation of the city’s middle-classes, but the majority of the population received ...