eBook - ePub

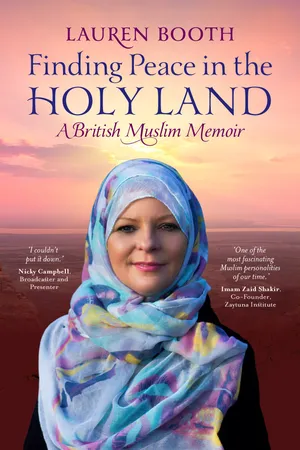

Finding Peace in the Holy Land

A British Muslim Memoir

Lauren Booth

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Finding Peace in the Holy Land

A British Muslim Memoir

Lauren Booth

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

- Lauren Booth is one of the UK's most curious Muslim converts, who can regularly be seen on major morning talk shows, and found in articles in national newspapers in the UK.

- Lauren Booth is often referred to as Tony Blair's sister-in-law. Although she is a prominent figure in her own right, this gives her instant name recognition, which translates all over the world - and has given her access to many historic figures that are mentioned in the book, such as the former leader of Hamas, Cat Stevens, and many British politicians.

- The book is very well written and fun to read. Her determined personality and rather abrupt sense of humour are on display throughout, leading her to say inappropriate things to religious scholars and take on challenges that risk her life.

- Covering her private and professional life, readers are treated to adventures onboard the Gaza flotilla, and insights about her family including her late father, Anthony Booth (a well-known British actor); her sister, Cherie Blair; and of course her brother in law, Tony Blair.

- With a major publicity campaign in preparation, and appearances at conferences in the US, Canada, Malaysia, Singapore, the Middle East and the UK all being planned, we expect this book to receive significant support.

- The author has links with the Daily Mail, The Sun, The Mirror in the mainstream, and many Muslim publications, so we believe articles and reviews about the author and the content of the book will appear, particularly as revelations about Tony Blair and her father's potential conversion to Islam will prove irresistible to reporters.

- The author also has a strong social media following across Twitter and Facebook, hosts a radio talkshow in Manchester and regularly appears on BritishMuslimTv and the Islam Channel.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Finding Peace in the Holy Land an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Finding Peace in the Holy Land by Lauren Booth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religious Biographies1

Paper Aspirations

‘Then he gave me his autographed picture.

And these three rusty nails.’

Roger McGough

And these three rusty nails.’

Roger McGough

IN 1967, HIGHGATE was a pretty cobbled village on the edge of a heath where my father, actor Anthony Booth – at the pinnacle of his fame (yet financially broke) – missed my own premiere in the maternity department of Whittington hospital. My mother, Pamela Riley (born Cohen), gave birth to her first daughter, Sarah Jane, with only my grandfather at the hospital to congratulate her. She was immediately anxious about the absence of the handsome, flighty father to-be, and hours after my birth and freshly stitched, she fled the hospital in search of him. She suspected he had sneaked out to some party or premier, leaving my newborn self to spend that first night in a hospital cot to ‘cry it out’, which was the neo-natal fashion at the time. Years later my mother would show me the note she had found taped to the end of her hospital bed on her return the next morning: ‘Enjoy the party! Hope you have a haemorrhage, love Nursey.’

My father was enjoying success in a TV show called Till Death us Do Part when I entered ‘stage right’ in my pushchair and intervened temporarily in his life. The part of the ‘Randy Scouse Git’ (translation: Lecherous, Liverpudlian Lout) was specially written for him by the screenwriter Johnny Speight as a foil to the main role of the racist, right-wing bigot, Alf Garnett. My father would admit, with his charming smile, the ‘Scouse git’ role suited him to a tee.

We moved several times in my early years, from pleasant Victorian house to rented apartment, each move dependent on my father’s wavering popularity and his determined inability to put aside some of the money from this brief fame for the (as it turned out) many and torrential ‘rainy days’ to come. By the time my baby sister arrived in 1970, our parents were miserably resident in the bedsit upstairs in my maternal grandparents’ semi-suburban home. It was not an especially happy time for the young family.

The traditional values of Sid and Frances Riley were at odds with the ‘Come the Revolution’ rhetoric and political activities of their ‘son in law’. Even that misnomer was a cause of bitterness, for my parents never actually married. The British way of life was changing; in the 1950s, society dictated your social status and one’s expected code of conduct in personal affairs was still broadly attached to Christian values. One man for one women, for life, in marriage. The 60s would usher in a ‘who cares’ rejection of forever-ness in relationships. It was ‘you only live once’: YOLO 1.0.

My father, true to his ‘Scouse git’ title, couldn’t have married anyway as he was not yet divorced from his American wife and mother of their two daughters, who had returned to America after they split. A pattern was already forming. We were not his first, nor his last, attempt at family life. In the early 50s my father met a pretty Northern girl who was also an aspiring actress. They married young and had two daughters. As his career in film and on stage began to take off he would tour and then work in London, leaving his lonely wife at the home where he had been born, overseen by his Liverpool-Irish mother, Vera. The intervals between my father’s visits back to Liverpool became longer and longer. After two or three years they more or less ground to a halt, he was too ‘busy’. Mother and daughters were left to survive as best they could in Waterloo, a less than salubrious area. The cramped home, a traditional two-up two-down midterraced house, was also shared by his younger brother, Robert, another aspiring actor.

Back in North London, the 70s rolled on. It was an era of which my grandmother, hunched over endless cups of tea, high-tar cigarettes and her personal Ouija board, called: ‘Godless times’. I was by all accounts a ‘bonny’ baby who rarely, if ever, cried. I had a mop of dark brown hair, beneath which my mother said ‘determined’ brown eyes looked straight into a person’s heart. The single close up photo that existed of me, long since lost, showed a boyish 1-year-old, sitting straight backed in a white lace dress staring directly at the person taking the photograph, her lips pulled thin into an exact replica of my father’s. This kid is ‘going places’, my parent’s groovy friends would say whenever it was, very occasionally, shown.

In 1970, Sid and Frances wanted no part in any revolution, ‘sexual’ or otherwise. The couple, then in their fifties, were dyed-in-the wool Tory voters and royalists. My grandfather, Sydney Seymour Riley, was an affable man who had served twenty-six years in the British army, from 1935 to 1961. During his youth in the hillside village of Haltwhistle, Cumbria, he was known as a stubborn, naughty lad. His family, farmers and small landowners, were not surprised when he signed up for the army at barely seventeen years old – lying about his age to recruitment officers.

During the Second World War granddad rose through the ranks, somewhat against the odds (his character remained quite wild), to become a Regimental Sergeant Major. My grandmother would recount tales of how he ‘made grown men cry’ during their induction: ‘Your mothers’ didn’t want you and the British army doesn’t want you in the state you’re in,’ he’d yell at quaking recruits. I could never quite believe this of the loving, sweet man who utterly doted on my sister and I from his beaten armchair in the corner of the living room. He earned the nickname ‘Spike’, for the running shoes he used in army competitive races, and he was a pretty good boxer as well. As he sat in his cigar-fragranced corner, my sister and I would occasionally coax a story from him about the fights he got into during the war, mostly as far as we could tell with Anzac soldiers who he had called an ‘insolent and disrespectful bunch’.

Spike was always besotted by my grandmother. They met in a Rhyl tearoom towards the end of the war. She had been waiting tables as he was ordering lunch, on leave from the nearby army base. From the moment she told him to ‘get lost’, he plotted to convince the rebellious local beauty to let him drive her to dinner on the handlebars of his bicycle.

My grandmother, Frances Clare Parr, was adopted. Her mother had been a young unmarried girl and the father’s surname on the birth certificate was the family name, indicating either a scandal or an attempt to cover it up. The poor girl gave birth in a convent, where she spent the rest of her life ‘atoning for her sins’. Frances, the parentless child, was a black haired girl with bright blue eyes. She was soon fostered by a humble family in the windy seaside town of Rhyl. Despite her feisty nature, the extended family grew to love her, and she loved them in return.

The memory of her mother’s single visit stayed in her mind. Unerringly bringing a tear to her misted blue eyes well into old age. In the linoleum kitchen over a bacon butty (sandwich) and a strong mug of tea with a dash of evaporated milk, she’d tell me the story again and again: ‘The lady appeared all in black, flowing robes. She had a bright, shining face which spoke of proud beginnings and great beauty, but her clothes scared me. I called for my adopted “Mam!” and backed away from her. I’ll never forget the terrible, sad, look on her face when she said,

“Frances, don’t you know me? I am your mother.”’ Perhaps this sad moment gave my grandmother the little, yet fervent, religious belief she had. I was no more than five years old when Nan taught my sister and me the ‘Lord’s Prayer’. In the double bed next to her own, she would never let us go to sleep without it being recited as we broiled under a dozen blankets on top of a simmering electric one.

It was kept a secret from my sister and me that our ‘real’ grandfather had been a smart young man from the only Jewish family in Rhyl. The marriage had ended in divorce and a bitter custody battle over my mother, which caused an unforgiving suspicion of men and ‘foreigners’ to take root in my grandmother’s character forever after.

When I was four years old, my parents had a momentary flurry of cash after my father signed a deal to appear in a series of movies known as the ‘Confessions’ films, four cheaply-made, poorly-scripted ‘comedies’ that attempted to capitalize on the success of the Carry On series of comedy films that were popular in the UK from the 1950s to the 1970s. My father was embarrassed to have to make the trite, filthy things, but we were so broke he had no choice. He was paid the princely sum of £5,000. Early in 1971, my mother and grandfather went hunting for a beautiful place where her babies could toddle, away from her mother’s clucking attention and where she could (perhaps) finally persuade her unreliable boyfriend to settle down.

Mum knew she had found the right place as they drove the green, looping roads of Hampstead Garden Suburb one sunny afternoon. Built in the early 1900s, Heathcroft was an elegant block of red-brick apartments with high ceilings. There were three open lawns, rose gardens and a poshsounding ‘Porters Lodge’, where mail and cleaned linen were delivered and collected. A van came twice a week, bringing basics door to door including milk and eggs. A real step up in the world after my grandparents’ bedsit.

Number 79 was on the top floor of one of the imposing, elegant buildings. It had a dark wood front door, an external lock-up, where paraffin for the heaters could be stored, and a brass letter box. This opened into a small cloakroom for boots and coats, and through an arched doorway the polished wooden floors opened out into a dining area with large white-edged dormer windows each overlooking the gardens, ravishing all year round. On the left of the narrow main hallway, my small room was next to the even smaller bathroom, whose pipes clanged a merry tune. Further down the passage was the kitchen on the left, my sister’s room and parent’s room on the right, and finally a large spare room alongside a double-aspect living room. After we moved in, Dad bought a second-hand Jaguar. Life looked grand.

From the age of five until I was ten years old I went to the New End Primary school, Hampstead. It was the school of choice for a number of actors’ kids, including Tim BrookeTaylor of the comedy show The Goodies. For a while, even the legendary Hollywood star Lee Remick was a fawned over playground mum.

In 1977, marching up the flowering high street with my Dad’s hand in mine, I had the world at my feet. I felt gloriously fashionable in my red corduroy dungarees and matching Kickers, strolling amongst the actors and poets of the fashionable suburb. My hair was red-brown, shoulder length and pulled into bunches. With Dad on my arm I felt great. Who cared if we took the bus because we had no cash for petrol for the gas-guzzling Jag? We would hop aboard the single decker 268 bus, which stopped at the end of our leafy road, and ignore the 210 bus if came past because we wanted our ‘special driver’. At 8:22 in the morning, the 268 would rip up the hill like a sports car at Brands Hatch.

‘Bloody hell kid, he’s going for it today!’ Dad would grin, lighting a roll-up.

The driver would open the doors and turn his handsome smile our way, I loved his thick black lip fur and his sparkling eyes.

‘How ya doing, Evel Knievel, don’t drive too crazy today all right, I’ve got a smashing hangover,’ Dad would wink. ‘Evel Knievel’ would take his cue and before we could take our seats the bus lurched forward, propelling us down the aisle, laughing, into the seats. Everyone on the bus (including the dangerous driver) loved my father. ‘What a character,’ the other passengers on the 268 would say in earshot, as we sat down.

The epitome of 70s panache, he’d swing down the road, my little hand adoringly clutching his, his shoulder length blonde hair bouncing off the neck of a beige roll-neck sweater. I would hear women audibly gasp as we went by. At other times, walking through Golders Green to shop at Mac Fisheries or browsing the high street for the Jewish food he loved, passers-by in plaid coats or working men’s boots would wave and shout: ‘All right Tony, stay away from the women now mate!’ The teachers in the staff room, the geezers outside pubs, the man in the butcher’s shop where we got sausages, when we could, and every newspaper seller who had a kiosk in North London – loved him to bits. At a time when film stars were becoming distant hyped-up figures, with the agents and PRs we are now familiar with, Tony Booth was a down to earth, man-of-the people, TV star.

One morning, running late for school as usual, Dad couldn’t find the ten pence needed to get us to New End on time. A sticky array of overflowing ashtrays were strewn across the coffee table from the night before, the glass which had originally protected the baize beneath had long ago been smashed – all signs of my parent’s issues. With my red and blue satchel on my shoulder, I waited silently in the living room doorway as Dad pulled dirty jeans over grim pyjamas. He hopped from one foot to the other, half sober. Running a huge hand through his long hair he gave me a wink. Shoving hands into his jeans front pockets, then the back ones, he swore.

‘No effin’ money, kid.’ I knew the drill. Shake his wool coat hanging by the front door, if it rattled risk the tobacco gluey pockets to pull out change. Today there was no sound. Still, Dad was never lost for a positive suggestion, even if his ideas often didn’t work out.

‘Right kid,’ he said. ‘Let’s play a fun game. You’re gonna put your hands down the back of the sofa and see if you can find any change. Then you’re going to go through all the trousers and coats in the hallway, right? Find more than five shillings and I’ll buy ya’ an ice cream after school. Deal?’

I ran to the orange and brown sofa, immersing myself elbow deep in the grotty fabric. Rizla papers, cigarette butts, bus tickets … metal. Three precious shillings were retrieved from the depths before Dad had rinsed his face and put on the Denim aftershave my Nan had brought him last Christmas. Another twelve pence was retrieved from the variety of, once upon a time, jazzy coats in the airing cupboard.

Twenty-five pence. We were rich!

Rich enough to take the school bus that day and to relish a heart-shaped ice cream with vanilla and strawberry centre after school. It never occurred to either of us to tell Mum about the find. Her plans for food and bills were boring.

The public never suspected that under Dad’s flared jeans, my father routinely wore less than fashionable, yellow striped pyjamas. Nor did they seem able to tell, as I could, that beneath the cheap cologne there was an alcohol-based tang from the increasing amount of alcohol he relied upon to cope with the fact his once promising career was derailing. By the mid-70s, my father was an out of control ‘social’ drinker. His refusal to toe the establishment line by agreeing to such things as standing up for the national anthem at film premiers earned him almost as bad a reputation as that of an abusive drunk. When Till Death ended after seven smash hit series spanning a decade, he was forced to ‘sign on’ at the Labour Exchange, receiving money from the government. Confessions films aside, we relied on these payouts for the next eight years.

One day, when I was around nine years old, my father was rooting through a hall cupboard looking for the missing pages of a script he’d been sent to look at by his agent, Mary Lee. He was desperate for work and the kitchen fridge boasted one egg, two beers and half a tomato from a bygone era. We were all tired of eating Findus crispy pancakes. Each day, letters came that the adults couldn’t face and these were shoved into a bulging drawer in the wooden chest of drawers in the hallway. My father swore under his breath as pages were scattered on the floor, counting: ‘Sixteen, seventeen, forty-seven, eighty-one … did they let some idiot child of the landed gentry send this out?’

I stood behind him, a sickly feeling climbing in my throat. Quietly, I tiptoed away to my room. On my bed was the dolly paper chain I had made earlier that morning. On one side they had pencil clothes drawn on, which I liked. There was a pair of dungarees for the girl one, plaid trousers on two, three had a swimsuit in stripes. I turned my artwork gently over. The other side had typing on it. I read some of the words out loud. I w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Prologue

- 1. Paper Aspirations

- 2. Keeping the Faith

- 3. Hot As Hell

- 4. Clown of Renown

- 5. Laughing For Labour

- 6. Just Breathe

- 7. Arabophobia

- 8. Jerusalem Syndrome

- 9. Hypocrisy to Hope

- 10. Welcome to the Jungle

- 11. In Search of Meaning

- 12. Without a Paddle

- 13. The Test of Life

- 14. The Green Light

- 15. Which Road to Take

- 16. Toward the Straight Path

- 17. Staying Human

- 18. Hungry for Truth

- 19. Called to Prayer

- 20. Back Home in Gaza

- 21. Imran and Waziristan

- 22. Faith of Our Fathers

- 23. A New Way of Life

- Epilogue

- Index

Citation styles for Finding Peace in the Holy Land

APA 6 Citation

Booth, L. (2018). Finding Peace in the Holy Land ([edition unavailable]). Kube Publishing Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/733676/finding-peace-in-the-holy-land-a-british-muslim-memoir-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Booth, Lauren. (2018) 2018. Finding Peace in the Holy Land. [Edition unavailable]. Kube Publishing Ltd. https://www.perlego.com/book/733676/finding-peace-in-the-holy-land-a-british-muslim-memoir-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Booth, L. (2018) Finding Peace in the Holy Land. [edition unavailable]. Kube Publishing Ltd. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/733676/finding-peace-in-the-holy-land-a-british-muslim-memoir-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Booth, Lauren. Finding Peace in the Holy Land. [edition unavailable]. Kube Publishing Ltd, 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.