![]()

1

Introduction

OUR MAIN GOAL is modeling credit risk for measuring portfolio risk and for pricing defaultable bonds, credit derivatives, and other securities exposed to credit risk. We present critical assessments of alternative conceptual approaches to pricing and measuring the financial risks of credit-sensitive instruments, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of current practice. We also review recent developments in the markets for risk, especially credit risk, and describe certain enhancements to current pricing and management practices that we believe may better position financial institutions for likely innovations in financial markets.

We have in mind three complementary audiences. First, we target those whose key business responsibilities are the measurement and control of financial risks. A particular emphasis is the risk associated with large portfolios of over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives; financial contracts such as bank loans, leases, or supply agreements; and investment portfolios or broker-dealer inventories of securities. Second, given a significant focus here on alternative conceptual and empirical approaches to pricing credit risk, we direct this study to those whose responsibilities are trading or marketing products involving significant credit risk. Finally, our coverage of both pricing and risk measurement will hopefully be useful to academic researchers and students interested in these topics.

The recent notable increased focus on credit risk can be traced in part to the concerns of regulatory agencies and investors regarding the risk exposures of financial institutions through their large positions in OTC derivatives and to the rapidly developing markets for price- and credit-sensitive instruments that allow institutions and investors to trade these risks. At a conceptual level, market risk—the risk of changes in the market value of a firm’s portfolio of positions—includes the risk of default or fluctuation in the credit quality of one’s counterparties. That is, credit risk is one source of market risk. An obvious example is the common practice among broker-dealers in corporate bonds of marking each bond daily so as to reflect changes in credit spreads. The associated revaluation risk is normally captured in market risk-management systems.

At a more pragmatic level, both the pricing and management of credit risk introduces some new considerations that trading and risk-management systems of many financial institutions are not currently fully equipped to handle. For example, credit risks that are now routinely measured as components of market risks (e.g., changes in corporate bond yield spreads) may be recognized, while possibly offsetting credit risks embedded in certain less liquid credit-sensitive positions, such as loan guarantees and irrevocable lines of credit, may not be captured. In particular, the aggregate credit risk of a diverse portfolio of instruments is often not measured effectively.

Furthermore, there are reasons to track credit risk, by counterparty, that go beyond the contribution made by credit risk to overall market risk. In credit markets, two important market imperfections, adverse selection and moral hazard, imply that there are additional benefits from controlling counterparty credit risk and limiting concentrations of credit risk by industry, geographic region, and so on. Current practice often has the credit officers of a financial institution making zero-one decisions. For instance, a proposed increase in the exposure to a given counterparty is either declined or approved. If approved, however, the increased credit exposure associated with such transactions is sometimes not “priced” into the transaction. That is, trading desks often do not fully adjust the prices at which they are willing to increase or decrease exposures to a given counterparty in compensation for the associated changes in credit risk. Though current practice is moving in the direction of pricing credit risk into an increasing range of positions, counterparty by counterparty, the current state of the art with regard to pricing models has not evolved to the point that this is done systematically.

The informational asymmetries underlying bilateral financial contracts elevate quality pricing to the front line of defense against unfavorable accumulation of credit exposures. If the credit risks inherent in an instrument are not appropriately priced into a deal, then a trading desk will either be losing potentially desirable business or accumulating credit exposures without full compensation for them.

The information systems necessary to quantify most forms of credit risk differ significantly from those appropriate for more traditional forms of market risk, such as changes in the market prices or rates. A natural and prevalent attitude among broker-dealers is that the market values of open positions should be re-marked each day, and that the underlying price risk can be offset over relatively short time windows, measured in days or weeks. For credit risk, however, offsets are not often as easily or cheaply arranged. The credit risk on a given position frequently accumulates over long time horizons, such as the maturity of a swap. This is not to say that credit risk is a distinctly long-term phenomenon. For example, settlement risk can be significant, particularly for foreign-exchange products. (Conversely, the market risk of default-free positions is not always restricted to short time windows. Illiquid positions, or long-term speculative positions, present long-term price risk.)

On top of distinctions between credit risk and market price risk that can be made in terms of time horizons and liquidity, there are important methodological differences. The information necessary to estimate credit risk, such as the likelihood of default of a counterparty and the extent of loss given default, is typically quite different, and obtained from different sources, than the information underlying market risk, such as price volatility. (Our earlier example of the risk of changes in the spreads of corporate bonds is somewhat exceptional, in that the credit risk is more easily offset, at least for liquid bonds, and is also more directly captured through yield-spread volatility measures.)

Altogether, for reasons of both methodology and application, it is natural to expect the development of special pricing and risk-management systems for credit risk and separate systems for market price risk. Not surprisingly, these systems will often be developed and operated by distinct specialists. This does not suggest that the two systems should be entirely disjoint. Indeed, the economic factors underlying changes in credit risk are often correlated over time with those underlying more standard market risks. For instance, we point to substantial evidence that changes in Treasury yields are correlated with changes in the credit spreads between the yields on corporate and Treasury bonds. Consistent with theory, low-quality corporate bond spreads are correlated with equity returns and equity volatility. Accordingly, for both pricing and risk measurement, we seek frameworks that allow for interaction among market and credit risk factors. That is, we seek integrated pricing and risk-measurement systems. A firm’s ultimate appetite for risk and the firmwide capital available to buffer financial risk are not specific to the source of the risk.

1.1. A Brief Zoology of Risks

We view the risks faced by financial institutions as falling largely into the following broad categories:

• Market risk—the risk of unexpected changes in prices or rates.

• Credit risk—the risk of changes in value associated with unexpected changes in credit quality.

• Liquidity risk—the risk that the costs of adjusting financial positions will increase substantially or that a firm will lose access to financing.

• Operational risk—the risk of fraud, systems failures, trading errors (e.g., deal mispricing), and many other internal organizational risks.

• Systemic risk—the risk of breakdowns in marketwide liquidity or chainreaction default.

Market price risk includes the risk that the degree of volatility of market prices and of daily profit and loss will change over time. An increase in volatility, for example, increases the prices of option-embedded securities and the probability of a portfolio loss of a given amount, other factors being held constant. Within market risk, we also include the risk that relationships among different market prices will change. This, aside from its direct impact on the prices of cross-market option-embedded derivatives, involves a risk that diversification and the performance of hedges can deteriorate unexpectedly.

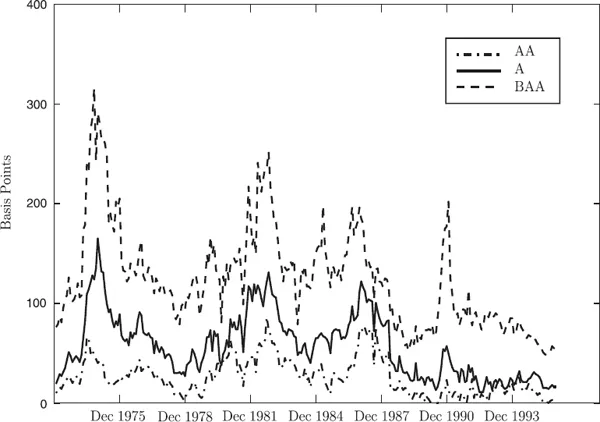

Credit risk is the risk of default or of reductions in market value caused by changes in the credit quality of issuers or counterparties. Figure 1.1 illustrates the credit risk associated with changes in spreads on corporate debt at various maturities. These changes, showing the direct effects of changes in credit quality on the prices of corporate bonds, also signal likely changes in the market values of OTC derivative positions held by corporate counterparties.

Liquidity risk involves the possibility that bid-ask spreads will widen dramatically in a short period of time or that the quantities that counterparties are willing to trade at given bid-ask spreads will decline substantially, thereby reducing the ability of a portfolio to be quickly restructured in times of financial stress. This includes the risk that severe cash flow stress forces dramatic balance-sheet reductions, selling at bid prices and/or buying at ask prices, with accompanying losses or financial distress. Examples of recent experiences of severe liquidity risk include

• In 1990, the Bank of New England faced insolvency, in part because of potential losses and severe illiquidity on its foreign exchange and interest-rate derivatives.

• Drexel Burnham Lambert—could they have survived with more time to reorganize?

• In 1991, Salomon Brothers faced, and largely averted, a liquidity crisis stemming from its Treasury bond “scandal.” Access to both credit and customers was severely threatened. Careful public relations and efficient balance-sheet reductions were important to survival.

• In 1998, a decline in liquidity associated with the financial crises in Asia and Russia led (along with certain other causes) to the collapse in values of several prominent hedge funds, including Long-Term Capital Management, and sizable losses at many major financial institutions.

Figure 1.1. Corporate bond spreads. (Source: Lehman Brothers.)

• In late 2001, Enron revealed accounting discrepancies that led many counterparties to reduce their exposures to Enron and to avoid entering into new positions. This ultimately led to Enron’s default.

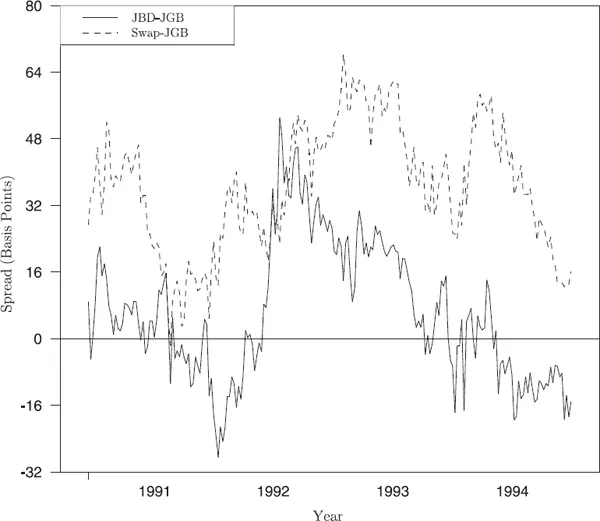

Changes in liquidity can also be viewed as a component of market risk. For example, Figure 1.2 shows that Japanese bank debt (JBD) sometimes traded through (was priced at lower yields than apparently more creditworthy) Japanese government bonds (JGBs), presumably indicating the relatively greater liquidity of JBDs compared to JGBs. (Swap-JGB spreads remained positive.)

Systemic risk involves the collapse or dysfunctionality of financial markets, through multiple defaults, “domino style,” or through widespread disappearance of liquidity. In order to maintain a narrow focus, we will have relatively little to say about systemic risk, as it involves (in addition to market, credit, and liquidity risk) a significant number of broader conceptual issues related to the institutional features of financial systems. For treatments of these issues, see Eisenberg (1995), Rochet and Tirole (1996), and Eisenberg and Noe (1999). We stress, however, that co-movement in market prices—nonzero correlation—need not indicate systemic risk per se. Rather, co-movements in market prices owing to normal economic fluctuations are to be expected and should be captured under standard pricing and risk systems.

Figure 1.2. Japanese bank debt trading through government bonds.

Finally, operational risk, defined narrowly, is the risk of mistakes or breakdowns in the trading or risk-management operations. For example: the fair market value of a derivative could be miscalculated; the hedging attributes of a position could be mistaken; market risk or credit risk could be mismeasured or misunderstood; a counterparty or customer could be offered inappropriate financial products or incorrect advice, causing legal exposure or loss of goodwill; a “rogue trader” could take unauthorized positions on behalf of the firm; or a systems failure could leave a bank or dealer without the effective ability to trade or to assess its current portfolio.

A broader definition of operational risk would include any risk not already captured under market risk (including credit risk) and liquidity risk. Additional examples would then be:

• Regulatory and legal risk—the risk that changes in regulations, accounting standards, tax codes, or application of any of these, will result in unforeseen losses or lack of flexibility. This includes the risk that the legal basis for financial contracts will change unexpectedly, as occurred with certain U.K. local authorities’ swap positions in the early 1990s. The risk of a precedent-setting failure to recognize netting on OTC derivatives could have severe consequences. The significance of netting is explained in Chapter 12.

• Inappropriate counterparty relations—including failure to disclose information to the counterparty, to ensure that the counterparty’s trades are authorized and that the counterparty has the ability to make independent decisions about its transactions, and to deal with the counterparty without conflict of interest.

• Management errors—including inappropriate application of hedging strategies or failures to monitor personnel, trading positions, and systems and failure to design, approve, and enforce risk-control policies and procedures.

Some, if not a majority, of the major losses by financial institutions that have been highlighted in the financial press over the past decade are the result of operational problems viewed in th...