![]()

PART I

ESSAYS

![]()

Liszt, Italy, and the Republic

of the Imagination

ANNA HARWELL CELENZA

Liszt’s first encounter with Italy has been told time and again in various guises: as a romance, a travelogue, and a Bildungsroman.1 Italy’s breathtaking beauty has been credited with luring him over the Alps. As Chateaubriand once said, “Nothing is comparable to the beauty of the Roman horizon, to the sweet inclination of the plains as they meet the soft and flowing contours of the hills.”2 Such sensual descriptions attracted many visitors to Italy, but there was more to Liszt’s travels than scenic diversion. When he journeyed south in 1837, he joined a steady stream of artists, aristocrats, writers, and musicians who for centuries had made the long and difficult trip. Like these travelers, Liszt was drawn by Italy’s reputation as the cradle of European culture, by the beauty of its art, and by the mystery of its past. Although it is true that he was in the middle of a scandalous relationship with Marie d’Agoult when he journeyed south with her, this was old news; their first child had already been born, in 1835. Liszt was escaping more than mere gossip when he left Paris. He was on a quest to discover his creative essence, a new artistic identity. Liszt had a “premeditated master plan” concerning the future course of his career, and during the second half of the 1830s he planned on “distinguishing himself” in intellectual pursuits that were accorded more prestige than mere performing—namely composition and literature.3 Italy offered beauty and comfort; but more important, it held the promise of an intellectually rich escape.

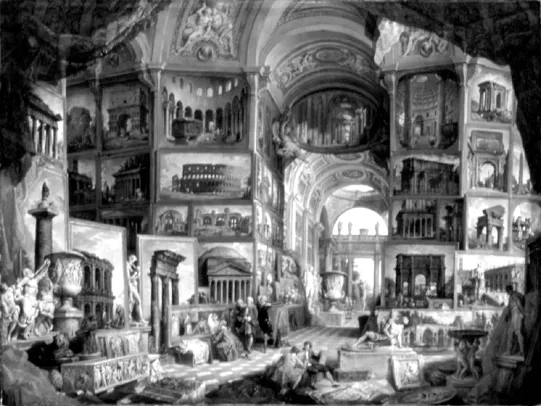

The image of Italy as a destination for the cultured and well educated took shape in the mid-eighteenth century. Painters such as Canaletto captured the beauty of Italian cities and landscapes, and archaeological excavations across the peninsula fueled a growing interest in antiquity. Scholars like Johann Joachim Winckelmann in Germany and Comte Anne-Claude-Philippe de Caylus in France pondered Italy’s ancient past. Their studies drew countless travelers from across Europe, and the Grand Tour became a required activity in the education of every “European gentleman.” Rome, in particular, served as a living textbook—the undisputed capital of the visual arts (figure 1).4 Some scholars have described Liszt’s first journey to Italy as his own Grand Tour.5 This description is valid as far as it goes, since it is clear that Liszt sought an education of sorts as he traveled. But self-enlightenment was not at the core of his motivation. Simply put, Liszt traveled to Italy to escape his own past. Troubled by the music politics he had recently experienced in Paris, he sought refuge, and Italy seemed the perfect sanctuary.

Scholars have mapped every step of Liszt’s journey, from the moment he first crossed the Alps to his twilight days in Tivoli late in life. My goal is somewhat different. Instead of describing “Liszt in Italy,” I reflect on the image of Italy he alluded to in his music, specifically the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage (Years of pilgrimage)—Deuxième Année: Italie (Second year: Italy).6 Liszt published this work in 1858, three years after Première Année: Suisse (First year: Switzerland), appeared.7 The first volume consists of nine pieces, all of which are related to impressions of nature and scenic Swiss locales. In contrast, the Italy volume contains seven pieces directly related to the visual arts and poetry of early-modern Italy:

“Sposalizio” (a painting by Raphael)

“Il penseroso” (a sculpture by Michelangelo)

“Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa”

“Sonetto 47 del Petrarca”

“Sonetto 104 del Petrarca”

“Sonetto 123 del Petrarca”

“Après une lecture du Dante (Fantasia quasi Sonata)”

In addition to revealing the art and literary works Liszt encountered in Italy, year two of Années de pèlerinage roughly replicates the itinerary he followed, from Milan and Venice to Florence and Rome.8 By the time he crossed the Alps, these cities had become reputed havens for political and social exiles. The end of the Napoleonic era marked a new chapter in the region’s history. Humbled politically, Italy had become a cultural refuge, “the Paradise of Exiles” as Shelley described it in 1824.9 Lord Byron had much to do with the creation of this image. In the final installment (Canto IV) of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (published in 1818), Byron blended the popular image of the poet as rebel and bearer of freedom with that of the social outcast and solitary wanderer. Italy offered self-exiles like Liszt a new start—a chance to face up to his mission as a “poet” in the Romantic sense of the word and define his artistic identity as an expatriate in a foreign land.

Various pieces in the first two volumes of Années de pèlerinage are framed by quotations from Cantos III and IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Like Byron, Liszt consciously created a public image of himself as a lone pilgrim, an intellectual “poet” whose travels across Switzerland served as the scenic prelude to a full artistic awakening in Italy. Liszt presented this Byronic image of himself to Parisian readers through a series of articles (commonly referred to as Lettres d’un bachelier ès musique) published in Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris and L’Artiste during his years abroad. The authorship of these articles has been a topic of debate for nearly a century. Although Liszt’s name appeared as the sole author, even he acknowledged that d’Agoult sometimes contributed to their production. To date, Rainer Kleinertz has given the most even-handed assessment of the Liszt-d’Agoult authorship issue. In the commentary to his edition of Liszt’s complete writings, Kleinertz describes d’Agoult’s contributions to various article drafts written between 1837 and 1841 and, in so doing, convincingly demonstrates that the overall structure and content of the articles should be attributed primarily to Liszt.10 Charles Suttoni expressed a similar opinion in his own study of Liszt’s literary works, claiming that they were the result of “an active and fluid literary partnership” where “Liszt’s ideas” were at times “expressed in d’Agoult’s words.”11 Despite their authorship, Liszt’s articles drew attention to his travel experiences and intellectual inquiries—they also highlighted many of the literary and artistic influences that later defined his Années de pèlerinage.

Figure 1. Giovanni Paolo Panini, Roma Antica, or Views of Ancient Rome with the Artist Finishing a Copy of the Aldobrini Wedding. Stuttgart, Staatsgallerie.

In recent years, scholars interested in Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage have concentrated on purely musical aspects, namely the composition’s genesis and form.12 My approach is markedly different. Focusing on the extra-musical origins of the Italy volume, I describe in detail the cultural and historical circumstances that informed Liszt’s reception of Italian art and literature. As I hope to demonstrate, the literary and artistic sources Liszt encountered during his travels across Italy profoundly influenced his self-image as a composer and his creation of Années de pèlerinage. In Liszt’s mind, Italy became part of an ideal landscape that I call the Republic of the Imagination. This term is closely tied to George Sand’s descriptions of a “republic of music” and “holy colony of artists” in her letters to Liszt.13 When Sand coined these ideas in the early 1830s, their political resonance was especially strong, and my use of the phrase Republic of the Imagination makes reference to this.14 Sand’s ideas clearly influenced Liszt’s perception of Italy; his Republic of the Imagination was a state of mind, an imaginary place where artists, writers, and musicians interacted freely, unbound by political or historical ties. Specifically, it was a creative space where Liszt interacted with an imagined community of artists derived from early-modern Italian art and literature.

The republic of music, already established by a leap of your young imagination, is still only a dream for me…. I blush with shame and confusion when I reflect seriously on my life and pit your dreams against my realities:…your noble presentiments, your beautiful illusions about the social effects of the art to which I have dedicated my life, against the gloomy discouragement that sometimes seizes me when I compare the impotence of the effort with the eagerness of the desire, the nothingness of the work with the limitlessness of the idea;—those miracles of understanding and regeneration wrought by the thrice-blessed lyre of ancient times, against the sad and sterile role to which it is seemingly confined today.17

Liszt’s self-doubt was exacerbated by the fact that Sigismond Thalberg had recently descended on Paris and was being hailed as “le premier pianiste du monde.”18 Intent on confronting this new “mysterious rival,” Liszt postponed his travel plans to Italy and returned to Paris.19 On 8 January 1837, he published a mean-spirited review of Thalberg’s music in the Revue et Gazette musicale. This article angered many of Liszt’s colleagues, especially the critic François-Joseph Fétis, who later came to Thalberg’s defense in an article of his own.20 Reactions such as this turned Liszt into something of a pariah in Parisian musical politics, and he soon took up his pen again—this time in the guise of a persecuted artist. In an article addressed “To a Poet-Voyager” (i.e., George Sand), Liszt expressed his desire to escape.21 Using language strikingly similar to that found in Madame de Staël’s novel Corinne ou Italie, he lamented Italy’s political misfortune and explained why it was the perfect refuge for “thos...