![]()

CHAPTER 1

Educational Attainment: Overall Trends,

Disparities, and the Public Universities We Study

THE SUBJECT OF this book—educational attainment in the United States—could hardly be more timely. Academics, framers of public policy, and journalists are united in bemoaning the failure of the United States in recent years to continue building the human capital it needs to satisfy economic, social, and political needs. In their book The Race Between Education and Technology, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz applaud America’s astonishingly steady and substantial educational progress during the first three quarters of the 20th century—and then are just as emphatic in calling attention to the dramatic falling off in the rate of increase in educational attainment since the mid-1970s.1 The chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Ben S. Bernanke, in remarks delivered at Harvard on Class Day 2008, told the assembled graduates that “the best way to improve economic opportunity and to reduce inequality is to increase the educational attainment and skills of American workers.”2 The New York Times columnist David Brooks has referred to “the skills slowdown” as “the biggest issue facing the country.”3 In writing about how to increase growth in America, David Leonhardt, also at the New York Times, says simply: “Education—educating more people and educating them better—appears to be the best single bet that a society can make.”4

Bernanke was wise to couch his argument in terms of educational attainment (which we generally equate with earning a degree) rather than just enrollment or years of school completed, for the payoff to completing one’s studies is much higher than the payoff to having “just been there” another year—the so-called “sheepskin” effect.5 In our view, too much discussion has focused on initial access to educational opportunities (“getting started”) rather than on attainment (“finishing”). It is noteworthy that in his first speech to a joint session of Congress (and then in his budget message), President Barack Obama emphasized the importance of graduating from college, not just enrolling.6

In any case, as Bernanke and others have stressed, the key linkage is between the formation of human capital and productivity. In his Class Day remarks, Bernanke observed: “The productivity surge in the decades after World War II corresponded to a period in which educational attainment was increasing rapidly.” Technological change and the breaking down of barriers to the exchange of information and ideas across boundaries of every kind have unquestionably increased the value of brainpower and training in every country. As President Obama has said: “In a global economy where the most valuable skill you can sell is your knowledge, a good education is no longer just a pathway to opportunity—it is a prerequisite.”7 Leonhardt adds: “There really is no mystery about why education would be the lifeblood of economic growth. . . . [Education] helps a society leverage every other investment it makes, be it in medicine, transportation, or alternative energy.”8 Nor are economic gains the only reason to assert the importance of educational attainment. The ability of a democracy to function well depends on a high level of political engagement, which is also tied to the educational level of the citizenry. A high level of educational attainment fosters civic contributions of many kinds.9

Even though our emphasis on “finishing” is meant to be a useful corrective to the sometime tendency to focus simply on “starting,” we hasten to add that there are of course dimensions of college success beyond just graduating that must also be kept in mind. The kind and quality of the undergraduate education obtained are plainly important. It would be a serious mistake to treat all college degrees as the same or to put so much emphasis on earning a degree that other educational objectives are lost from sight. This is why some are skeptical of the weight given by the National Collegiate Athletic Association to graduation rates (whatever the subject studied and whatever the rigor of the graduation requirements) in assessing the academic performance of scholarship athletes. As in platform diving, differences in the “degree of difficulty” of various courses of study deserve to be acknowledged, and considerable weight should be given to academic achievement in assessing educational outcomes. For these reasons, we examine fields of study chosen by students and grades earned, as well as graduation rates. However, much as there is to be said for such finer-grained analyses, we believe it is valuable to place special emphasis on graduation rates as presumptively the single most important indicator of educational attainment—which is what we do in this book.

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT IN THE UNITED STATES

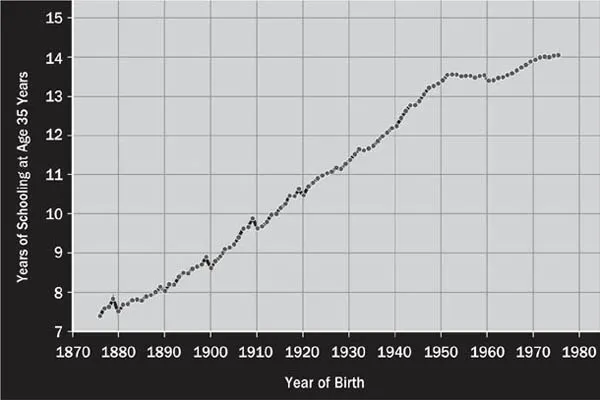

These basic propositions explain why there is reason for serious concern about the slow-down in the rate of increase in the overall level of educational attainment in the United States. The facts are sobering. As Goldin and Katz report on the basis of an exhaustive study of historical records, the achievements of America in the first three quarters of what they call “the Human Capital Century” are impressive indeed. This country’s then unprecedented mass secondary schooling and the concurrent establishment of an extensive and remarkably flexible system of higher education combined to produce gains in educational attainment that were both steady and spectacular (see Figure 1.1, which plots years of schooling by birth cohorts from 1876 to the present). Unfortunately, this truly amazing record of progress came to a halt about the time when members of the 1951 birth cohort (who were 24 years old in 1975) were attending college.10

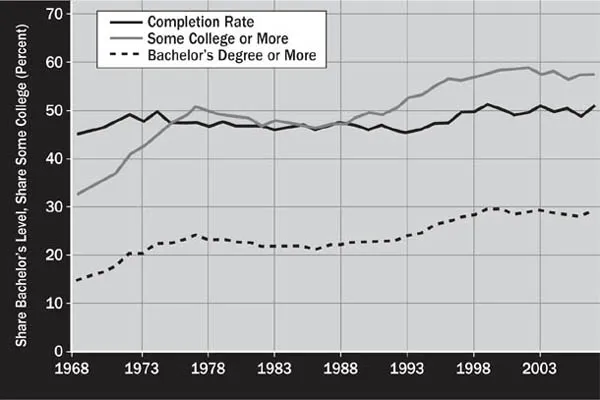

We see this same “flattening” when we use data from the Current Population Survey to track the educational attainment of 25- to 29-year-olds from 1968 to 2007 (Figure 1.2). Although there was a modest increase in educational attainment in the 1990s, the curve is flat for the years thereafter. The failure of educational attainment to continue to increase steadily is the result of problems at all stages of education, starting with pre-school and then moving through primary and secondary levels of education and on into college (see the discussion in Chapter 2 of “losses” of students at each main stage of the educational process). Our focus on completion rates at the college level should certainly not be read as dismissing the need to make progress at earlier stages. In any case, it is noteworthy that over this 40-year period the completion rate (the fraction of those who started college who eventually earned a bachelor’s degree) changed hardly at all, while time-to-degree increased markedly.11

This is not a pretty picture when looked at through the lens of America’s history of educational accomplishments during the first 75 years of the 20th century. It is an equally disturbing picture when juxtaposed with the remarkable gains in educational attainment in other countries. As is increasingly recognized, the United States can no longer claim that it is “first-in-class” in terms of continuing progress in building human capital. The 2008 annual stock-taking document produced by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that the 2006 higher education attainment rate for 25- to 34-year-olds in the United States is nearly identical to that of 55- to 64-year-olds, a group 30 years their senior. In 2006, the United States ranked 10th among the members of the OECD in its tertiary attainment rate. This is a large drop from preceding years: the United States ranked 5th in 2001 and 3rd in 1998. Moreover, in the United States only 56 percent of entering students finished college, an outcome that placed this country second to the bottom of the rank-ordering of countries by completion rate.12 In recognition of this reality, President Obama has set an ambitious goal for American higher education: “By 2020, America will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.”13 And the situation in the United States is even more worrying when the focus is on degrees in the natural sciences and engineering. According to a report published by the National Science Board, “The proportion of the college-age population that earned degrees in NS&E fields was substantially larger in more than 16 countries in Asia and Europe than in the United States in 2000.” In that year, the United States ranked just below Italy and above only four other countries. Twenty-five years earlier, in 1975, the United States was tied with Finland for second place (below only Japan).14

Figure 1.1. Years of Schooling of U.S. Native-Born Citizens by Birth Cohorts, 1876–1975

Source: Goldin and Katz, figure 1.4.

Figure 1.2. Educational Attainment of 25- to 29-Year-Olds, 1968–2007

Source: Current Population Survey.

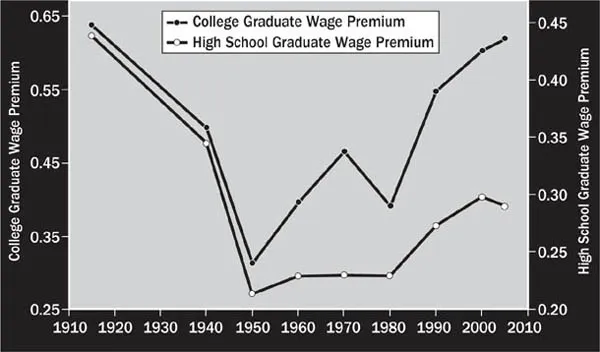

A central question is why educational attainment in the United States has been on a plateau in recent years. In seeking to answer this question, a key analytical tool is the wage premiums earned by college graduates and high school graduates. Data painstakingly assembled by Goldin and Katz (presented in Figure 1.3) show that both of these premiums fell sharply between 1915 and 1950, moved somewhat erratically between 1950 and 1980, and then increased sharply from 1980 to 2005—with the wage premium for college graduates increasing much faster than the premium for high school graduates. By 2005, the wage premium for college graduates had returned to the high-water mark set in 1915.15

In looking inside these ratios, Goldin and Katz found that the growth rate of demand for more educated workers (relative to less educated workers) was fairly constant over the entire period from 1915 to 2005. It was the pronounced slow-down in the rate of growth in the supply of educated workers (especially native-born workers) that was primarily responsible for the marked increase in the college graduate wage premium. In recent years, growth in the supply of college-educated workers has been sluggish and has not kept up with increases in demand—especially inceases in the demand for individuals with strong problem-solving skills and degrees from the more selective undergraduate programs and leading professional schools.16 The real puzzle is why educational attainment has failed to respond to the powerful economic incentives represented by the high college graduate wage premium. We would have expected rising returns on investments in a college education to have elicited a solid increase in the number of students earning bachelor’s degrees.17 But this has not happened.

Figure 1.3. Wage Premiums of College Graduates and High School Graduates, 1915–2005

Source: Goldin and Katz, figure 8.1.

To be sure, some commentators have suggested that the perception that there are superior economic returns to investments in higher education is mistaken; however, careful statistical work by several leading economists strongly suggests that these worries are misplaced. Indeed, research reported and reviewed by David Card (among others), suggests that returns for prospective college students who might be added “at the margin” are at least as high as the average for all students.18 As Goldin and Katz put it, there may be some “natural limit” to the share of high school graduates who can benefit from earning a college degree—the optimal graduation rate is surely not 100 percent—but there is no evidence that we are anywhere close to such a limit now.19

Thus, the sluggish response of educational attainment to economic incentives remains puzzling, and we are driven back to the need to understand the forces responsible for what appears to be a “supply-side” block. One possible explanation for the surprisingly stagnant state of overall educational attainment in the United States can be rejected out of hand: the problem is not low aspirations. Students of all family backgrounds have high (and rising) educational aspirations. The Education Longitudinal Study of 2...