![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The financial system promotes our economic welfare by helping borrowers obtain funding from savers and by transferring risks. During the World Financial Crisis, which started in 2007 and seems to have ebbed as we write in 2010, the financial system struggled to perform these critical tasks. The resulting turmoil contributed to a sharp decline in economic output and employment around the globe.

The extraordinary policy interventions during the Crisis helped stabilize the financial system so that banks and other financial institutions could again support economic growth. Though the Crisis led to a severe downturn, a repeat of the Great Depression has so far been averted. The interventions by governments around the world have left us, however, with enormous sovereign debts that threaten decades of slow growth, higher taxes, and the dangers of sovereign default or inflation.

How do we prevent a replay of the World Financial Crisis? This is one of the most important policy questions confronting the world today, and it remains unanswered. In this book, we offer recommendations to strengthen the financial system and thereby reduce the likelihood of such damaging episodes. Though informed by the lessons of the Crisis, our proposals are guided by long-standing economic principles.

When developing our recommendations, we think carefully about the incentives of those who will be affected and about unintended consequences. We try to identify the specific problem to be solved and the divergence between private and social benefits behind that problem; we carefully examine the possible unintended effects of our proposed solution; and we consider ways in which individuals or institutions can circumvent the regulation or capture the regulators.

Two central principles support our recommendations. First, policymakers must consider how regulations will affect not only individual financial firms but also the financial system as a whole. When setting capital requirements, for example, regulators should consider not only the risk of individual banks, but also the risk of the whole financial system. Second, regulations should force firms to bear the costs of failure they have been imposing on society. Reducing the conflict between financial firms and society will cause the firms to act more prudently.

In the remainder of this book we present a series of policy proposals, each of which can be read on its own or in combination with the others. The conclusion summarizes these proposals and shows how they might have helped during the World Financial Crisis.

WHAT HAPPENED IN THE WORLD FINANCIAL CRISIS?

The Prelude

The first symptoms of the World Financial Crisis appeared in the summer of 2007, as a result of losses on mortgage backed securities. For example, in August, BNP Paribas suspended the redemption of shares in three funds that had invested in these securities, and American Home Mortgage Investment Corp. declared bankruptcy. Mortgage related losses continued throughout the fall, and indicators of stress in the financial system, including the interest rates that banks charge each other, were unusually high. Despite huge injections of liquidity by the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, financial institutions began to hoard cash, and interbank lending declined. Northern Rock was unable to refinance its maturing debt and the firm collapsed in September 2007, becoming the first bank failure in the United Kingdom in over 100 years.

The next big problem was in the market for auction rate securities. Although auction rate securities are long-term bonds, short-term investors found them attractive before the Crisis because sponsoring banks held auctions at regular intervals—typically every 7, 28, or 35 days—to allow the security holders to sell their bonds. Thousands of the auctions failed in February 2008 when the number of owners who wanted to sell their bonds exceeded the number of bidders who wanted to buy them at the maximum rate allowed by the bond and, unlike in previous auctions, the sponsoring banks did not absorb the surplus. After much litigation, the major sponsoring banks agreed to pay many of their clients’ losses. The market for auction rate securities has not revived.

Bear Stearns’ failure in March 2008 proved, in retrospect, a critical turning point. The firm had funded much of its operations with overnight debt, and when it lost a lot of money on mortgage backed securities, its lenders refused to renew that debt. At the same time, customers ran from its prime brokerage business, a process we describe in detail below. Over the weekend of March 15, the U.S. government brokered a rescue by J.P. Morgan that included a generous commitment by the Federal Reserve. Many observers and officials thought that the Crisis was contained at this point and that markets would police credit risks aggressively. That hope proved unfounded.

The Remarkable Month of September 2008

The World Financial Crisis moved into an acute phase in September 2008.1 Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, large government-sponsored enterprises that create, sell, and speculate on mortgage backed securities, failed during the first week of September and were placed under the conservatorship of the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

The peak of the Crisis started on Monday, September 15, 2008. Lehman Brothers, a brokerage and investment bank headquartered in New York, failed with a run by its short-term creditors and prime brokerage customers that was similar to the run experienced by Bear Stearns. Lehman’s bankruptcy was a surprise, since the government had stepped in to prevent the bankruptcy of Bear Stearns only months before.

Within days, the U.S. government rescued American International Group. AIG had written hundreds of billions of dollars of credit default swaps, which are essentially insurance contracts that pay off when a specific borrower, such as a corporation, or a specific security, such as a bond, defaults. As economic conditions worsened and it became increasingly likely that AIG would have to pay off on at least some of its commitments, the swap contracts required the firm to post collateral with its counterparties. AIG was unable to make the required payments. Goldman Sachs was AIG’s most prominent counterparty, and Goldman’s demands for collateral were an important part of AIG’s demise. The cost to taxpayers of government assistance for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and AIG is now projected at hundreds of billions of dollars.

That same week, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson announced the first Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), asking Congress for $700 billion to buy mortgage backed securities. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and President George W. Bush also gave important speeches warning of grave danger to the financial system. The Securities and Exchange Commission banned the short-selling of several hundred financial stocks, causing pandemonium in the options market, which relies on short-selling to hedge positions, and among hedge funds that employed long-short strategies.2

The turmoil of the week did not stop there. Interbank lending declined sharply, the commercial paper market slowed to a crawl, and there was a run on the Reserve Primary Fund, a money market mutual fund. Unlike other mutual funds, money market funds maintain a constant share price, typically $1, by using profits in the fund to pay interest rather than to increase share values. Because the share price is fixed at $1, losses that push a fund’s net asset value below $1 per share can trigger a run, as investors rush to claim their full dollar payments and force the losses onto other investors. The Reserve Primary Fund, which had more than 1 percent of its assets in commercial paper issued by Lehman, suffered just such a run on September 16, 2008. After Lehman declared bankruptcy, the fund’s net asset value dropped to $0.97 per share and investors withdrew more than two-thirds of the Reserve Fund’s $64 billion in assets before the fund suspended redemptions on September 17. Concern spread to investors in other money market funds, and they withdrew almost 10 percent of the $3.5 trillion invested in U.S. money market funds over the next ten days. To stabilize the market, the government took the unprecedented step of offering a guarantee to every U.S. money market fund.

In normal times, any one of these events would have been the financial story of the year, yet they all happened in the same week in September 2008. Although much commentary and popular press coverage blames the World Financial Crisis entirely on the government’s decision to let Lehman fail, such an analysis ignores the evident contributions of the many other momentous events that occurred during that week.

October 2008: The Bank Bailout and Credit Crunch

By early October 2008, the U.S. government realized that the TARP plan to buy mortgage backed securities on the open market was not feasible. Instead, the Treasury Department used the appropriated money to purchase preferred stock in large banks, and to provide credit guarantees and other support. Though now remembered as the “bank bailout,” the TARP purchases were not simply a transfer to failing institutions. Healthy banks were also forced to accept capital in an attempt to mask the government’s opinions about which banks were in more trouble than others. Many policymakers seemed to think that banks were not lending because they had lost too much capital and were not able or willing to raise more. Thus, the goal seemed to be not to save the banks but to recapitalize them so they would lend again. In the end, the former result was achieved—none of the large banks that received TARP funds failed—but the latter, arguably, was not. We analyze these issues in detail below, and recommend some alternative structures and policies that we believe would have worked better.

During much of the World Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve experimented with a wide range of new facilities beyond its traditional tools of interest rate policy and open market operations. The Fed lent broadly to commercial banks, investment banks, and broker-dealers, and ended up buying commercial paper, mortgages, asset backed securities, and long-term government debt in an effort to lower interest rates in these markets. By December 2008, excess reserves in the banking system had grown from $6 billion before the Crisis to over $800 billion. These actions are not a focus of our analysis, but they surely helped prevent the Crisis from turning into another Great Depression. At a minimum, they eliminated most banks’ concerns about sources of cash.

Bank failures in Europe in the fall of 2008 led to more direct bailouts. The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg spent $16 billion to prop up Fortis, a major European bank with about $1 trillion in assets. The Netherlands spent $13 billion to bail out ING, a banking and insurance giant. Germany provided a $50 billion rescue package for Hypo Real Estate Holdings. Switzerland rescued UBS, one of the ten largest banks in the world, with a $65 billion package. Iceland took over its three largest banks, and its subsequent difficulties highlight what happens when the cost of bailing out a country’s banks exceeds the government’s resources.

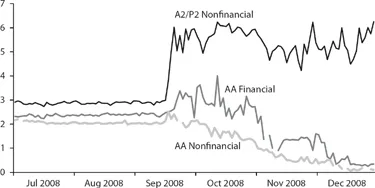

Throughout the fall of 2008, there was a “flight to quality” in markets around the world. When investors are worried about default, they demand higher interest rates. Yields on securities with any hint of default risk rose sharply, especially in the financial sector.

The flight to quality is apparent in the interest rates on commercial paper, in Figure 1. Commercial paper is short-term unsecured debt issued by banks and other large corporations and is an important part of their financing. The commercial paper rates for financial institutions and lower-credit quality borrowers jumped in September and October, but after a small increase, the rate for large creditworthy nonfinancial companies actually declined. The rate on U.S. Treasury bills, which are viewed as the most secure investment, also fell; the three-month Treasury bill rate actually dropped to zero for brief periods in November and December 2008.

Figure 1: Annualized Percent Yields on 30-Day High-Quality (AA) Financial and Nonfinancial Commercial Paper and Medium-Quality (A2/P2) Nonfinancial Commercial Paper, in Percent, August to December 2008. Source: Federal Reserve

THE RUN ON THE SHADOW BANKING

SYSTEM

The panic that struck financial markets in the fall of 2008 has been characterized as a run on the shadow banking system, and with good reason. Before the Crisis, many bonds, mortgage backed securities, and other credit instruments were held by leveraged non-bank intermediaries, including hedge funds, investment banks, brokerage firms, and special-purpose vehicles. Many of these intermediaries were forced to “delever” during October and November, selling assets to repay their creditors.

Hedge funds and other leveraged intermediaries use the securities in their portfolios as collateral when they borrow money. During the World Financial Crisis, many wary lenders decided the collateral borrowers had posted before the Crisis was no longer sufficient to guarantee repayment. When the lenders demanded either more or better collateral, many borrowers were forced to sell their levered positions and repay their loans. The result was a reduction in the quantity of assets they held and in their leverage. In addition, hedge funds and other intermediaries suffered large withdrawals by panicky customers, again forcing them to sell securities on the market. The assets being sold were generally acquired by individual investors, the federal government, or commercial banks, which as a group financed most of their purchases by borrowing from the government.3

The financing difficulties faced by arbitrageurs and liquidity providers are apparent in a series of fascinating market pathologies. In financial markets, there are often many different ways to obtain the same outcome. An investor can use many different combinations of securities, for example, to risklessly convert dollars today into dollars in six months. The actions of arbitrageurs usually keep the costs of the different approaches closely aligned. During the fall of 2008, the costs often diverged, with the approach that required more capital typically costing less.4

The principle of covered interest parity, for example, says that after eliminating exchange rate risk, risk-free investing should have the same return in every currency. An investor who wants to invest dollars today and receive dollars in the future usually buys a U.S. bond. He could accomplish the same thing by converting his dollars into euros, investing in a riskless euro bond, and locking in the conversion of the euro payoff back into dollars with a forward contract. Since both strategies convert dollars today into dollars in the future, they should have the same return.5 Suppose instead the return on the U.S. bond is lower. Then an arbitrageur could borrow money in the United States at the lower rate, invest it in the euro transaction at the higher rate, and make a profit.

During the Crisis, covered interest parity violations as large as 20 basis points (0.20 percent) emerged.6 This may seem trivial, but in normal times these violations rarely exceed 2 basis points. Moreover, traders can usually “lever up” transactions like this and make a large profit. But that’s the catch—hedge funds, brokerages, and investment banks were being forced to delever during the Crisis, and 20 basis points is not enough to entice many long-only investors to replace the U.S. bond they are currently holding with a foreign bond and some seemingly complicated currency transactions.

Other recent research finds similar di...