![]()

Part I

The Polish Campaign

The outbreak of the Second World War disrupted millions of lives and plunged Europe once again into a bloody conflict. Hitler’s attack on Poland had been long in coming, since the Right never accepted Germany’s defeat and the Nazi movement made reversing the “shame of Versailles” into one of its chief propaganda themes. In spite of protestations of peacefulness in order to mislead domestic and international opinion, the Third Reich systematically rearmed, preparing for a second conflict to be waged more ruthlessly and successfully. Hitler cleverly used the reluctance of the victors to grant Germans rights of ethnic self-determination as cover to conquer Austria, annex the Sudetenland, dismantle Czechoslovakia, and demand a transportation corridor to East Prussia. When the West failed to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union and he succeeded in buying Stalin’s neutrality on August 23, 1939, war became inevitable. Because German civilians remembered the privation of the First World War, many of them were notably unenthusiastic about another struggle.

Konrad Jarausch was mobilized and sworn in on September 1, 1939, since he was still young enough to serve and not essential enough to the home front to be exempted. Although he had been drafted in June 1918 and trained for the field artillery, he had been saved from going to the front by the armistice in November. Because he had been transferred to the reserves after his thirty-eighth birthday in February 1938, he was called up as a member of battalion V/XI of the Landesschützen (territorial defense forces) from Magdeburg. As an academic he was anything but military in physique or bearing, yet he complied out of a Prussian sense of duty and also because he wished to participate in a historic event that he had missed the first time around. Surprisingly enough, he was quickly promoted to the rank of Obergefreiter (private first class) on October 1, 1939, and to Unteroffizier (noncommissioned officer) on January 1, 1940. This initial advancement was a result of the Wehrmacht’s need for competent personnel as well as of his superiors’ recognition of his leadership abilities.

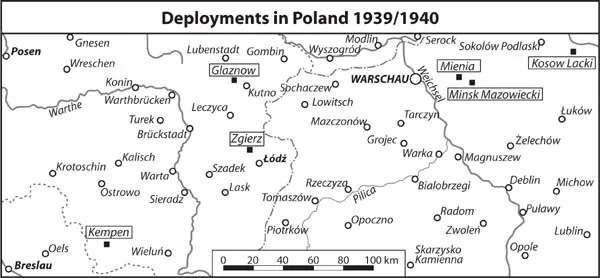

Like many other soldiers, my father observed the rapid victory over Poland with amazement and gratitude. On paper, both sides fielded almost equal numbers of troops, tanks, and airplanes, but in practice the fighting quickly turned into a rout. Britain and France failed to mount a relief attack in the West, while on September 17 the Soviet Union occupied the Eastern Polish territories according to the provisions of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, taking advantage of Poland’s focus on the West. The Poles fought gallantly, but the Wehrmacht had better equipment and a superior strategic position, invading from three sides at once: in the north from East Prussia, in the middle from Brandenburg, and in the south from Silesia. With giant pincer movements the German army bottled up the Polish forces around Warsaw and eventually defeated the remnants around Lublin. During the fierce fighting not only the SS but also the regular army began to commit atrocities against Jews and Polish civilians, prefiguring what would become the Holocaust. When on October 6 the Polish army capitulated, Hitler had won his first, perhaps all too easy, blitzkrieg victory, cementing his popularity.

As a member of the reserves, Konrad Jarausch was assigned to security duties during the Polish campaign and its aftermath. Due to reports of guerrilla activity, the Landesschützen were used to secure significant objects like train stations and search the woods for snipers behind the Army Group South in the former Prussian province of Posen. His own unit was ordered to guard POWs, who continued to be captured in large numbers due to the rapid advance. This responsibility involved selecting ethnic Germans who could be sent home quickly, picking out Poles who had to be controlled until the fighting was over, and identifying Jews, increasingly subject to anti-Semitic persecution. Because of his intellectual training Jarausch tended to be assigned to writing reports, giving background lectures, or leading small groups of guards. Repelled by the often rough and alcohol-centered comradeship of army life, he nonetheless strove for a degree of acceptance in his troop. Although these tasks kept him away from the fighting, they brought Jarausch close enough to the front to witness the war’s devastating effects.

Unlike many of his comrades, he developed a keen interest in the conquered country and people, wondering how Germans and Poles might be able to live together in the future. To begin with, Konrad Jarausch was fascinated by the east central European landscape in which he discovered many similarities to his native Brandenburg. At the same time, he was appalled by the poverty of many rural towns where he detected architectural traces of earlier aristocratic rule, subsequent Prussian administration, and the new national Polish state. As a practicing Protestant, he was also interested in his own denomination’s conflation with German nationality and in the Catholic piety of the Poles, which he saw as one of the sources of their patience in suffering and pride in their own culture. In order to bridge the gap between occupier and occupied, he also tried to learn a bit of the Polish language. While welcoming the return of former Prussian provinces, he was less sure about the success of ethnic resettlement schemes and of harsh Germanization policies. As a historian he sensed that a new order had to rest on more than force and would need to leave space for a degree of Polish identity.

Konrad Jarausch saw the suffering of the war through the lens of the nationalities’ struggle, somewhat tempered by a sense of Christian humanism. His credulity regarding tales of German victimization and gladness over the “liberation” of lost territories show that he shared some of the prejudices that justified harsh occupation measures as necessary retaliation. But his descriptions of the streams of refugees and of the plight of the defeated Poles evince a considerable amount of sympathy for the human cost of the conflict. Similarly, he seems to have been both repelled by and attracted to the Jews whom he encountered because he used linguistic stereotyping along with astute observations in the same description. On the one hand he graphically portrayed the hunger and filth of Jewish ghetto life, but on the other hand he also recognized a superior intelligence that evoked compassion. Only occasionally did he note atrocities, citing their official justifications without making it clear how far he really believed in them. While his letters document the existence of racist crimes in Poland, they also indicate these were still limited, because units like his own were not involved in them.

During the initial stage of the fighting, he viewed the war with ambivalence, alternating between elation about German victories and despair over the final outcome. Konrad Jarausch was willing to put up with a considerable amount of personal discomfort as long as he had a sense of participating in a grand reshaping of history, which would be told and retold as a heroic tale by future generations. Like many of his comrades he was delighted with the speed and extent of the German advance in the East, which had taken years to accomplish in World War I. But he was also concerned that the surprising ease of the victory in Poland would reinforce a set of nationalist attitudes and racial prejudices that might eventually undermine German domination, since it was likely to foster unthinking arrogance. Especially in the letters to his brother-in-law, he remained acutely aware that the real war in the West had not yet begun and that Poland was at best a first step. Unlike many other soldiers, Konrad Jarausch therefore thought about the war in long-range terms and continued to worry about the unpredictability of its ultimate outcome.

Deployments in Poland, 1939–1940

His aims as a Prussian and German patriot overlapped to a considerable degree with the Nazi program of expansion, but eventually also parted ways with the racial imperialism of the SS. Undoing the perceived injustice of Versailles, restoring prior Prussian territories, and even consolidating scattered German settlements in the annexed Warthegau around Posen might still be justified by the precedent of the Holy Roman Empire and a belief in the superiority of German culture. But completely extinguishing Polish identity or murdering an entire Jewish people went beyond his imagination and exceeded his feeling of what would be “right.” Moreover, he considered many of the Nazi exploitation measures or SS atrocities counterproductive to the German cause, because they would engender eternal hatred. At the same time, these policies violated his sense of humanism, based on his reading of the Greek and Roman classics, as well as the precepts of his intense, scriptural Christian faith. During his entire service he wrestled with the irresolvable dilemma of wanting to support the war effort, while doubting its moral justification and worrying about its political consequences.

![]()

Letters from Poland,

September 1939 to January 1940

Arrival in the East

September 9, 1939

Dearest Lotte,

After an eighteen-hour trip we arrived this morning in a very rural and peaceful area right near the German border by Gross-Wartenberg.1 The trip was tolerable. We now have a seven-kilometer march ahead of us. Where we’ll go from there, no one knows. In any case, we are in the East. We traversed the route I’ve become familiar with, one that I traveled just two months ago as I went on to Oels.2 Now relax and don’t worry too much about me. I have in fact up until now managed to get through everything that was demanded of us in terms of my health and there isn’t any danger of battle here. Be well. I’m thinking of you always.

Your

Konrad

Initial Impressions

September 9, 1939

Now we’re moving again. We’re sitting, comfortably and cozily, in a third-class compartment. The sun is shining on the peaceful, quiet countryside. A German fighter buzzes once over a field. I had an interesting night. I was sent to do telephone duty; it was a mistake, but because of it I spent a wonderful hour at my post for the first time in a thickly wooded park under a star-studded sky, and I chatted with the housekeeper for fifteen minutes. Today we’re seeing real East German vistas and everything that goes along with it—large estates with manors, parks, and halls. Wide swathes of land. Between those, there are woods, deer, and hares. A temporary airfield lies between them. On the roads, steady streams of transports and trucks. Single batteries. Ambulances. At the crossing, a sign announces “158 km to Lodz.”3 We are starting a sort of gypsy existence. One day here, the next, somewhere else. It’s easier not to unpack one’s things. The experienced infantrymen show us how to pile them up next to us on the straw. I slept well under my coat until it began to get light. At that point we had to get out of our “beds” anyway. In the large hall of the inn where we’re quartered, there are over a hundred men. We still have it rather easy in regard to these externals. Since I only got to our quarters at 11:30, I picked out a little corner all to myself.

Even the train trip had at least something gypsylike about it, especially during the night. I fell into a deep sleep right after Magdeburg and woke up only after Rosslau.4 Then I took turns either standing at the door or eating. It was really lovely that you kept me so well supplied, especially with fruit. There was hardly anything to drink. The trip went quickly, except for the deepest hours of the night; at times it was fully dark in the compar...