![]()

Current Kisses

From the perspective, or rather the feeling state, of contemporary architectural discourse, there is something thrilling about taking a walk on the wild side of video and lingering over obscure historical examples of quirky design. On the one hand, they provide an opportunity to commit disciplinary and historical tourism and to experience the momentary pleasures of dalliance without duration. But at the same time that such flirtation could be described as simply a means of giving architecture a breath of fresh air from outside the field, the fact that it feels fresh is symptomatic both of the nature and of the need for revitalizing the relationships between mediums in general. The effect of talking about video sculpture or store windows as though they were architecture is exactly, in discursive terms, the effect sought by the theory of kissing in material terms. Both rely on two things that seem to be the same—two surfaces, two spaces, two forms, two mouths—but that turn out to be different and to generate a difference that can only be experienced in the moment of their contact.

Writing about kissing might not be the best way to seduce architecture into a contemporary performance, but it is a good way to teach it to count to two. The most direct way for architecture to go beyond itself is to work with and through other mediums. Herzog and de Meuron and Jean Nouvel have been particularly adept at this kind of addition (fig. 24). A second way of counting is simply to call something that is not architecture by a new name, like superarchitecture, and then to try to put it back together with architecture as a proper name. The potential effects on architecture—whereby building ends up with more than it started with—made by the analysis of Rist’s and Aitken’s work belongs to this category. A third technique for counting past one is to radicalize the terms by which we understand—and generally limit and control—architecture itself. The moment that architecture is no longer required to perform as an organic unity, it can develop the combination of empirical distinctiveness and perceptual singularity that characterizes the kiss as event. If the interior ceases to be understood as simply the natural consequence of an envelope or if the exterior is no longer understood to be the passive result of a building mass, interiors and exteriors can assume enough identity of their own that their reimplantation in building constitutes the electric move from one to two.

24. Ateliers Jean Nouvel, DR Concert Hall, 2009. Copenhagen

Some contemporary architectural practices are exploring this third alternative. They have begun to rediscover the interest in investing the interior with particularity rather than merely relegating the interior to the status of an inevitable by-product of construction: simply a building’s inside. The exchange between artists and architects and the various values they have attached to the interior (or the exterior and the differences between them) may begin to explain this development. For example, the issues of gender and domesticity that now preoccupy Rist were of primary importance to certain architects during the 1990s, although her libertine excesses with respect to interior furnishings seem ahead of today’s architectural pace. The result of these two entwined perspectives is an interior understood independently from how it is used and yet dependent on the material that shapes use. Such an interior is conceived as semiautonomous: in the singular moment of perception it is inseparable from its architectural surroundings but is also empirically and descriptively distinct. This is the state of complex coincidence, which has been dubbed a confound, that generates the bedazzling states of difference and identity embedded in a kiss.18

Recognizing the productive charge of the confound can push architecture to overcome its disciplinary disappointment at not being able to be totally self-sustaining and to relinquish its fantasy of absolute autonomy and coherence. When the interior is conceived of independently, it divides the architectural medium into parts, into at least a twosome. So the first effect of shaping the interior as distinct from architecture is the interruption of the discipline’s pursuit of utopia, which it has primarily sought through the erasure of boundaries between interiors and exteriors in favor of continuous, undifferentiated spatial extension. But contemporary architectural practices have also discovered that an interior cannot exist independently; it always fuses with architecture in the moment of actual reception, a moment that is not repeatable. The second effect of giving the interior distinction, then, is that the differentiated interior demands design consideration and intensity, both as such and in its intercourse with building. The interior cannot be an architectural leftover or vaguely understood as abstract space but rather is an element that, like a projected image, can both obscure architecture (and hence mitigate its attachment to its own protocols) and, at the same time, rely on architecture (and hence reinforce its irreducible qualities). And in this doubled relation, in this moving to more than one and sometimes two, architecture and the interior enfold around one another to produce the ever surprising and never still experience of the perceptually new and experientially singular.

Preston Scott Cohen’s addition to the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, currently under construction, exemplifies the explosive potential of the contemporary interior when conceived as semiautonomous. Because kissing is a logic and theory of part to whole and because Cohen is a supreme geometer, it should come as no surprise that his building also has a kissable exterior in the sense that the skin has many faces in convivial rapport, even if the building as a whole lacks faciality. But my interest lies in what I consider to be the building’s “interior,” not the galleries or the space inside the envelope but rather the “Lightfall,” a core that cuts through the full section and brings light from top to bottom. “Lightfall” is geographically in the center of the building, deep inside the museum. But that is not why it is an interior. Nor does “Lightfall” provide interior space—it is an unoccupiable void that visitors look through and a semisolid figure that visitors look at and meander around. “Lightfall” is an intruder in the museum that causes a conceptually constituted interior to emerge. The core captures, moves, and shapes light while its exotic contours hold together and intensify these luminous and always changing effects. Its swirling form and agitated grisaille resonate throughout the building and cause, only in the moment of perception, an unstable interior to come into being. The core is both anomaly and raison d’être—the interior’s guarantor of continuous perceptual novelty and affective vividness. Without “Lightfall” the building would have a perfectly serviceable, indeed a really great inside, but it would lack an interior.

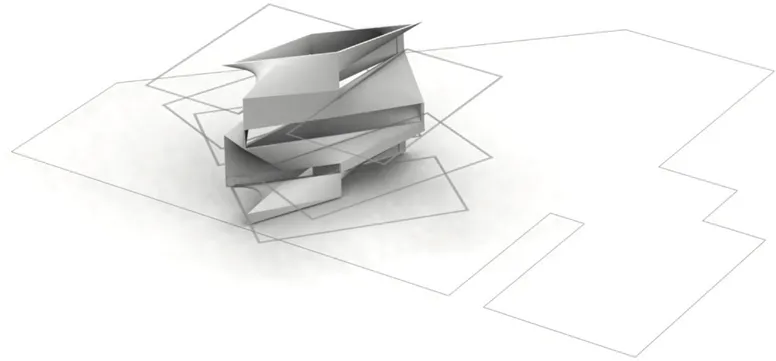

A drawing and an anecdote best reveal the ontologically rupturous implications of this assertion. One of the first and most widely circulated images of this addition was a three-dimensional model of the light core sitting atop a two dimensional plan (fig. 25). The “combine” was no doubt made to explain the geometry by showing how simple lines can lead to complex shapes. But the effect of the combine resides in the inexplicably erotic allure of the central and protruding model. Its white surfaces seem nude without their building around them, asking to be looked at and loved by J. J. Winckelmann himself, the greatest admirer of complex white bodies known to the history of art. And like all good centerfolds, Cohen’s “Lightfall” became an instant best seller (fig. 26). Images of the core frolicked in the international press, giving the architect the beginnings of wide fame and celebrity. And yet this total identification of the building with the core turns out to have led to fantasies of escape and separation. For no good reason, for none of the reasons typically associated with significant design changes late in the game, such as the demands of value engineering, Cohen toyed with the idea of excising “Lightfall” from the scheme. It is possible that the very success of the media campaign that featured “Lightfall” in isolation led to this seemingly perverse desire to eliminate it. Yet the fact that the plan and the figure were represented from the beginning in two different mediums indicates that they were always detachable and susceptible to distinct empirical description. Cohen chose to keep “Lightfall” in, but the very fact that it was possible for him to consider removing it underscores that his design was not conceived in the manner of Alberti, who defined good design as one in which no part can be added or taken away without destroying the “beautiful music.”19 The Tel Aviv Museum of Art makes its effect precisely by being made of different elements—in this case most notably inside and interior—that only make music in the friction of their imperfect coincidence. By developing a kind of multiple personality order, the building is able to receive a kiss from its own interior.

25. Preston Scott Cohen, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2004-2010. Computer diagram

26. Preston Scott Cohen, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2004-2010. Model photograph. As shown in the exhibition “Skin + Bones: Parallel Practices in Fashion and Architecture,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, November 19, 2006–March 5, 2007

Architects who are commissioned to work only on a building’s interior generally express disdain and disappointment: disdain because interiors are associated with decorators rather than discipline, and disappointment in being forced to contend with an existing building. The conviction that doing it all is always preferable to doing a part is not just narcissistic; it also comes from the commitment to an idea of architecture as a seamless unity. Yet as the Tel Aviv Museum of Art suggests, there is freedom to be gained in giving up the whole building and the building as a whole. The doubleness of superarchitecture can only emerge in the presence of at least two not perfectly coincident elements, a twoness that I diagrammed through the interplay of architecture and video because that is where the development is easiest to see. But superarchitecture can also emerge from within architecture itself, as long as architecture is not conceived as a totality. One can almost hear “Lightfall” saying to its building, “The basic concept was not to try to destroy or be provocative to the architecture, but to melt in. As if I would kiss . . .” It seems a fair exchange: autonomy and unity for contact and conviviality.

Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, perhaps more than any other architects working today, have long been interested in the relation of architecture to other mediums and in how this relation plays a uniquely central role in constructing architecture’s understanding of itself. In that sense, their firm’s work has always been more than architecture, a kind of superarchitecture that adds to the field by picking up ideas found by digressing outside architecture’s conventional parameters. In the early phases of its research, however, the extra value ironically came from cutting architecture down and up and crossways, using critical detachment and dismemberment as analytic tools and analysis as a form of creative production. In the context of the Reagan era, architecture for sure needed to get cut down to size and helped, even if against its will, to understand its limitations. Diller + Scofidio offered up some serious tough love. It divided architecture into so many pieces that any effort to put them together always produced something more and less than a whole, like a body that, after an autopsy, is missing organs, fluids, and tissue samples but has gained a scar. Necrophiliacs aside, the coroner’s office for most people induces discomfort rather than lust, and suturing things together in the dead is mostly done for reasons of cosmetic expedience rather than erotic consilience. Coroners are more interested the signs of a bite than a kiss, and the early work of D+S worked hard and well to take Greenberg’s avant-gardism farther from the meaty appetites than he could have ever imagined.

A powerful example of what happened to architecture when conceived of as a corps morcelé rather than object of potential affectation is The withDrawing Room, a 1987 installation in what had been the space of the Capp Street Project in San Francisco, the first residency program in the United States devoted to installation art (fig. 27). Recalling Matta-Clark’s “Splitting,” D+S dissected the building and its furnishings and moved parts around. Unlike Matta-Clark, however, D+S put the parts back together. Sort of. Contained in a single building, “Splitting” had parts that could and were shown entirely independently in different spaces at different times, a chunk of the building here, a photomontage there. The withDrawing Room was a single installation, a genre that like an establishing shot in film functions to provide for the viewer an embracing armature. But with chairs hanging from the ceiling like ghostly suicides, Murphy beds scarring the floor, and walls sliced up and left exposed, the installation’s valiant efforts to suture everything back together were destined—indeed, designed—to fail and left the cracks and fissures painfully evident. The installation, after all, was set in a room for withdrawing (not a boudoir or bordello or other rooms associated with drawing out), which makes it clear that the performance of criticality effects and oppositional detachment intentionally precluded getting it on. The project’s tragic power lay precisely in the inability of its parts to make contact with one another, a perfect because...