![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Rise of Private Regulation in the World Economy

On 28 August 2008, the world financial community awoke to stunning headline news: the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the powerful U.S. financial market regulator, had put forth a timetable for switching to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), produced by the International Accounting Standards Board—a private-sector regulator based in London. SEC-regulated U.S. corporations were to be required to use IFRS, possibly as soon as 2014.1 Only a decade earlier, the suggestion that the United States might adopt IFRS “would have been laughable,”2 as many experts expected U.S. standards to become the de facto global standards.

The SEC’s decision to defer to an international private standard-setter is part of a broader and highly significant shift toward global private governance of product and financial markets. What is at stake? Financial reporting standards specify how to calculate assets, liabilities, profits, and losses—and which particular types of transactions and events to disclose—in a firm’s financial statements to create accurate and easily comparable measures of its financial position. The importance of these standards, however, runs much deeper. Through the incentives they create, financial reporting standards shape research and development, executive compensation, and corporate governance; they affect all sectors of the economy and are central to the stability of a country’s financial system. IFRS, however, differ in some important respects from U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the financial reporting standards so far required by the SEC.3 Having evolved in a very litigious business environment, U.S. GAAP are highly detailed and address a vast range of specific situations, protecting companies and auditors against lawsuits. IFRS, by contrast, have traditionally been principles-based. They lay out key objectives of sound reporting and offer general guidance instead of detailed rules.

The implications of a switch from U.S. GAAP to IFRS are therefore momentous: twenty-five thousand pages of complex U.S. accounting rules will become obsolete, replaced by some twenty-five hundred pages of IFRS. Accounting textbooks and business school curricula will have to be rewritten, and tens of thousands of accountants retrained. Companies will need to spend millions of dollars to overhaul their financial information systems; many will need to redesign lending agreements, executive compensation, profit sharing, and employee incentive programs.4 And investors as well as financial analysts will need to learn how to interpret the new figures on assets, liabilities, cash flow, and earnings. The implications run deeper still. As explained by Robert Herz, chairman of the organization producing U.S. GAAP—the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB): “Liv[ing] in a world of principles-based standards involves [far-reaching] changes—institutional changes, cultural changes, legal and regulatory changes.”5 In sum, the proposed shift of rule-making authority from the domestic to the international level will affect numerous and diverse actors, and bring deep changes to the American financial market.

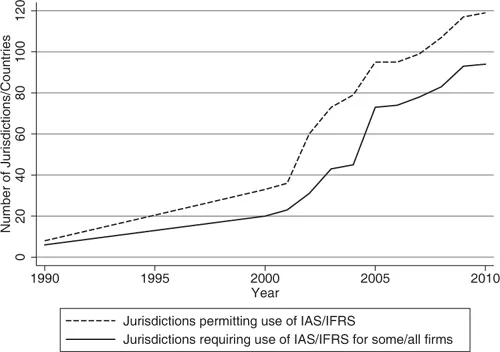

The United States is not the only country to switch to international standards, of course. As figure 1.1 shows, the number of jurisdictions where stock market regulators permit or even require the use of IFRS has exploded since 2001—despite the substantial costs of the switch for many countries’ firms, investors, and regulators.6 In the member states of the European Union (EU) and about sixty other countries across all continents, the use of IFRS is already mandatory for companies with publicly traded financial securities (stocks and bonds).7 And the trend is continuing: government regulators of several additional countries, including Japan, Canada, Brazil and India, have committed themselves to requiring IFRS in the near future.8

Figure 1.1 Use of IAS/IFRS as Allowed or Required by Stock Market Regulators

Number of jurisdictions permitting use includes number requiring use. Sources: IASC, Survey of the Use and Application of International Accounting Standards (1988); Cairns, International Accounting Standards Survey 2000 (2001); Nobes, GAAP 2000: A Survey of National Accounting Rules (2001); Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, “Use of IAS for Reporting by Domestic Companies, by Country” (2002), “Use of IFRS for Reporting by Domestic Listed Companies, by Country” (2004), IAS in Your Pocket (2001, 2002), and IFRS in Your Pocket (2003, 2005–10).

The global convergence of accounting standards is driven, in large part, by the international integration of financial markets and the increasingly multinational structure of corporations. These developments have not only led to economic growth and greater profits for many, but have also raised the costs of continued cross-national divergence of financial reporting standards for companies and investors. Indeed, cross-national differences in these rules are said to have exacerbated the global financial crisis of 2008–9—and the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–98 before it. The belief that harmonization would bring substantial benefits has prompted firms and governments to push for a single common set of international financial reporting standards. Harmonization promises to increase the cross-national comparability of corporate information, improve the transparency of financial statements for shareholders, investors, and creditors, as well as achieve greater efficiency and stability in global capital markets.

Switching to IFRS, however, also brings costs, and these costs vary across countries. For countries with marginal capital markets and no proper accounting tradition, the costs are relatively minor.9 However, they can be considerable for countries or regions with large and sophisticated capital markets as well as long-standing domestic accounting traditions, such as the United States and many European countries. These costs will be larger the greater the difference between IFRS and long-established domestic rules and practices. Americans and Europeans therefore have particularly strong incentives to seek to influence the process of global rule-making in accounting. International standards that end up being identical or very similar to a country’s domestic standards will minimize that country’s costs of switching to “international” rules. And in highly competitive international markets, differential switching costs may jeopardize even the survival of disadvantaged firms. In sum, the international harmonization of financial standards promises substantial benefits but also will bring significant costs for some and hence distributional conflicts.10 Given the enormous stakes involved, the battle over global rules is likely to be intensely fought, especially between the United States and Europe.

The shift of financial rule-making to the IASB is part of a striking and much wider—yet little understood—trend that is the focus of this book: the delegation of regulatory authority from governments to a single international private-sector body that, for its area of expertise, is viewed by both public and private actors as the obvious forum for global regulation. In that particular issue area, such a private body is what we call the focal institution for global rule-making. This simultaneous privatization and internationalization of governance is driven, in part, by governments’ lack of requisite technical expertise, financial resources, or flexibility to deal expeditiously with ever more complex and urgent regulatory tasks. Firms and other private actors also often push for private governance, which they see as leading to more cost-effective rules more efficiently than government regulation.11

Besides the IASB, two such private regulators stand out: the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). These organizations, in which states and governments as such cannot be members, are best described as centrally coordinated global networks comprising hundreds of technical committees from all over the world and involving tens to thousands of experts representing industries and other groups in developing and regularly maintaining technical standards. ISO and IEC jointly account for about 85 percent of all international product standards.

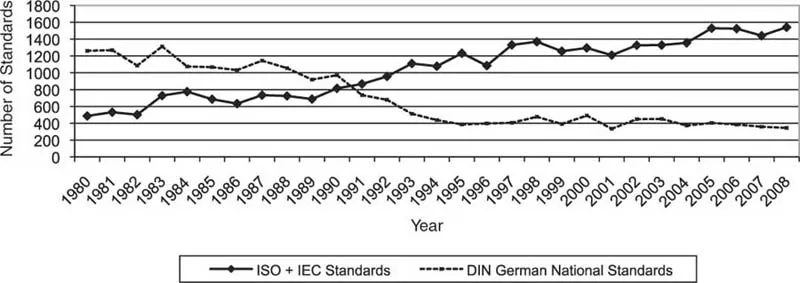

Product standards are technical specifications of design and performance characteristics of manufactured goods.12 Cross-national differences in these standards matter little when product markets are predominantly domestic. The global integration of product markets, however, has greatly and lastingly increased international interdependence and thus created strong incentives to coordinate on common technical solutions. International standards offer such a solution. ISO and IEC product standards, in particular, play a critical role in facilitating international trade and boosting economic growth. Their numbers have been growing steadily over the last twenty-five years while the production of national standards has dwindled—as illustrated by the declining number of new German (DIN) standards shown in figure 1.2.

Little known until the mid-1980s, ISO and IEC have become prominent, in part because of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, negotiated during the Uruguay Round trade negotiations from 1987 to 1994. This agreement obliges all member states of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to use international standards as the technical basis of domestic laws and regulations unless international standards are “ineffective or inappropriate” for achieving the specified public policy objectives.13 Regulations that use international standards are rebuttably presumed to be consistent with the country’s WTO obligations, whereas the use of a standard that differs from the pertinent international standard may be challenged through the WTO dispute settlement mechanism as an unnecessary nontariff barrier to trade and thus a violation of international trade law.

The commitment by governments to use international rather than domestic standards has enormous economic significance. Governments adopt hundreds of new or revised regulatory measures each year, in which product standards are embedded or referenced.14 And government regulations are just the tip of the iceberg, since consumer demand and concerns about legal liability create strong incentives for firms to comply with a wealth of product standards that are not legally mandated but define best practice.

The shift from domestic regulation to global private rule-making brings substantial gains, particularly to multinational and internationally competitive firms, for which it opens up commercial opportunities previously foreclosed by cross-national differences in standards and related measures. The share of U.S. exports affected by foreign product standards, for instance, had risen from 10 percent in 1970 to 65 percent in 1993, and by the time the WTO’s TBT-Agreement came into force, cross-national differences in product standards were estimated to result in a loss of $20–$40 billion per year in U.S. exports alone.15 United States imports and consumers were also affected. For some manufacturing industries, U.S. nontariff barriers in the late 1980s created losses due to increased costs and reduced trade equivalent to a tariff of 49 percent.16 Even today, about one third of global trade in goods—valued at $15.8 trillion for 2008—is affected by standards that often differ across countries, and the boost in trade from a complete international harmonization of product standards would be equivalent to a reduction in tariffs by several percentage points.17 A shift to common international standards thus benefits internationally competitive firms by increasing their export opportunities. It also benefits consumers who, as a result of increased trade and competition, have access to a broader range of goods and services and can buy them more cheaply.

Figure 1.2 New Domestic and International Standards per Year, 1980–2008

Sources: Annual reports and private communications from DIN, DKE, IEC, and ISO.

At the same time, the shift to global private-sector regulation also entails costs. To comply with international product standards, for example, firms may have to redesign their products, retool their production methods, or pay licensing fees to other firms whose proprietary technology may be needed to implement the international standard efficiently. These costs can be massive, to the point where some feel forced to discontinue production of certain goods or even go out of business.18

In sum, while the convergence on a single set of international standards may bring overall gains for all countries, those gains may differ greatly across countries and especially across firms. Firms therefore have a strong incentive to...