![]()

PART I

ESSENTIALS OF FLOWER

DESIGN AND FUNCTION

![]()

Chapter 1

WHY POLLINATION IS INTERESTING

Outline

- Which Animals Visit Flowers?

- Why do Animals Visit Flowers?

- How do Flowers Encourage Animal Visitors?

- What Makes a Visitor into a Good Pollinator?

- costs, Benefits, and Conflicts in Animal Pollination

- Why is Pollination Worth Studying?

The flowering plants (angiosperms) account for about one in six of all described species on earth and provide the most obvious visual feature of life on this planet. In the terrestrial environment, their interactions with other living organisms are dominant factors in community structure and function; they underpin all nutrient and energy cycles by providing food for a vast range of animal herbivores, and the majority of them use animal pollinators to achieve reproduction. Most of the routine “work” of a plant is carried out by roots and leaves, but it is the flowers that take on the crucial role of reproduction.

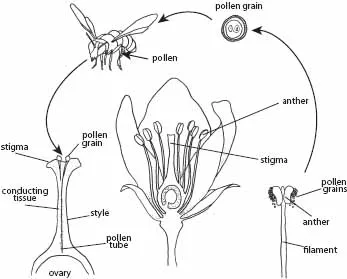

A flower is usually hermaphrodite, with both male and female roles. Hence it is essentially a structure that produces and dispenses the male gametophytes (pollen), organizes the receipt of incoming pollen from another plant onto its own receptive surfaces on the stigma, and then appropriately guides the pollen’s genetic material to the female ovules. The flower also protects the delicate male and female tissues (stamens and pistils) and has a role in controlling the balance between inbreeding and outbreeding, hence influencing the genetic structure and ultimately the evolutionary trajectory of the plant. But the plant itself is immobile, so that incoming pollen has to be borne on some motile carrier, sometimes wind or water but much more commonly on a visiting animal. To quote one source (Rothrock 1867), “among plants, the nuptials cannot be celebrated without the intervention of a third party to act as a marriage priest”! A pictorial overview of the stages is shown in figure 1.1, covering the processes of pollination that are the focus of this book.

A flower also serves to protect the pollen as it germinates and as the male nucleus locates the egg and then to protect the ovules as they are fertilized and begin their development into mature seeds. However, these later events (germination of the pollen and fertilization of the ovule) are technically not part of pollination, and they are covered here only as needed to understand the characteristics and effects of pollen transfer.

Since flowers bring about and control plant reproduction, they are central to much of what goes on in the terrestrial world, and pollination is a key mutualism between two kingdoms of organisms, perhaps the most basic type of exchange of sex for food; the plant gains reproductive success, and the animal—usually— gains a food reward as it visits the plant. But the visitor does not “want” to be a good pollinator and has to be manipulated by the plant to move on and to carry pollen to another plant. In practice, only about 1% of all pollen successfully reaches a stigma (Harder 2000).

Nevertheless, pollination by animals (biotic pollination) is both more common (Renner 1998) and usually more effective than alternative modes of abiotic pollen movements using wind or water, and animal pollination is usually also associated with more rapid speciation of plants (Dodd et al. 1999; K. Kay et al. 2006). Discussion of animal pollination therefore dominates this book, and around 90% of all flowering plants are animal pollinated (Linder 1998; Renner 1998). Furthermore, plants are, of course, the foundation of all food chains on the planet, and their efficient pollination by animals to generate further generations is vital to ensure food supplies for animals. Natural ecosystems therefore depend on pollinator diversity to maintain overall biodiversity. That dependence naturally extends to humans and their agricultural systems too; about one-third of all the food we eat relies directly on animal pollination of our food crops (and the carnivorous proportion of our diet has some further indirect dependence on animal pollination of forage crops). Pollination and factors that contribute to the maintenance of pollination services are vital components to take into account in terms of the future health of the planet and the food security and sustainability of the human populations it supports.

Figure 1.1 The central processes of pollination in a typical angiosperm flower, with the route taken by pollen from anther to stigma (followed by pollen tube growth into the style) in an animal-pollinated species. (Modified from Barth 1985.)

Beyond its practical significance, the flower-animal mutualism has been a focus of attention for naturalists and ecologists for at least two hundred years and provides almost ideal arenas for understanding some of the fundamental aspects of biology, from evolution and ecology to behavior and reproduction. It is perhaps more amenable than any other area to providing insights into the balance and interaction of ecological and evolutionary effects (Mitchell et al. 2009). Flowers are complex structures, and their complexity admirably reveals the actions, both historical and contemporary, of the selective agents (mainly, but not solely, the pollinators) that we know have shaped them. These factors make floral biology an ideal resource for understanding biological adaptation at all levels, in contrast with many other systems, where there are multiple and often uncertain selective agents.

In this first chapter, some of these central themes are introduced to set the scene for more specialist chapters; it should be apparent from the outset that while each chapter might stand alone for some purposes, it cannot be taken in isolation from this whole picture.

1. Which Animals Visit Flowers?

At least 130,000 species of animal, and probably up to 300,000, are regular flower visitors and potential pollinators (Buchmann and Nabhan 1996; Kearns et al. 1998). There are at least 25,000 species of bees in this total, all of them obligate flower visitors and often the most important pollinators in a given habitat.

There are currently about 260,000 species of angiosperms (P. Soltis and Soltis 2004; former higher estimates were confounded by many duplicated namings), and it has been traditional to link particular kinds of flowers to particular groups of pollinators. About 500 genera contain species that are bird pollinated, about 250 genera contain bat-pollinated species, and about 875 genera predominantly use abiotic pollination; the remainder contain mostly insect-pollinated species, with a very small number of oddities using other kinds of animals (Renner and Ricklefs 1995).

The patterns of animal flower visitors differ regionally. In central Europe, flower visitors over a hundred years ago were recorded as 47% hymenopterans (mainly bees), 26% flies, 15% beetles, and 10% butterflies and moths; only 2% were insects outside these four orders (Knuth 1898). But in tropical Central America, the frequencies would be very different, with bird and bat pollination entering the picture and fewer fly visitors, while in high-latitude habitats the vertebrate pollinators are absent and flies tend to be more dominant. Some of these patterns will be discussed in chapter 27.

2. Why Do Animals Visit Flowers?

The majority of flower visitors go there simply for food, feeding on sugary nectar and sometimes also on the pollen itself. Chapters 7 and 8 will therefore deal in detail with these commodities, and chapter 9 will cover a few more unusual foodstuffs and rewards that can be gathered from flowers; chapter 10 will take an economic view of all these food-related interactions, in terms of costs and benefits to each participant. Major themes in other chapters include the ways that flower feeders can improve their efficiency: learning recognition cues to select between flowers intra- and interspecifically, learning handling procedures, learning to avoid emptied flowers, and avoiding some of the hazards of competing with other visitors.

Flowers are also sometimes visited just as a convenient habitat, often simply because they offer an equable sheltered microclimate for a small animal to rest in, a place that is somewhat protected against bad weather, predators, or parasitoids. Or flowers may offer a reliable meeting site for mates or hosts or prey, or for females an oviposition site providing shelter for eggs and larvae. More rarely they are used as a warming-up site by insects in cold climates, usually because the flowers trap some incoming solar radiation, which enhances their own ovule development, but occasionally because a few flowers can achieve some metabolic thermogenesis that warms their own tissues (chapter 9 will provide more details on this topic).

3. How Do Flowers Encourage Animal Visitors?

Many plant attributes contribute to attraction of visitors: J. Thomson (1983) usefully groups these as plant presentation. Some of these attributes are readily apparent to visitors, and these may be features of individual flowers (e.g., color, shape, scent, reward availability, or time of flowering) or features of whole plants or groups of plants (e.g., flower density, flower number, flower height, or spatial pattern). The more readily apparent plant presentation traits can be divided into attractants (advertising signals), dealt with mainly in chapters 5 and 6, which discuss visual and olfactory signals, and rewards (usually foodstuffs), dealt with in chapters 7–9. Aspects of the timing and spacing of flowers, and how these might be affected by competition between different flowering plants, are given more in-depth treatments in chapters 21 and 22.

Other floral attributes are more cryptic to the visitor and may only determine the reproductive success of the plant in the longer term; these might include pollen amounts, ovule numbers, the genetic structure of the plant population, the presence and type of incompatibility system, etc.

It is generally in the plant’s interest to support and even improve its visitors’ efficiency, encouraging them to go to more flowers of the same species (so ensuring that only conspecific pollen is taken and received) and to go to flowers with fresh pollen available and/or with receptive stigmas for pollen to be deposited upon. Many flowers therefore add signals of status to their repertoire, via color change, odor change, or even shape change. Visitors are thereby directed away from flowers that are too young or too old or already pollinated. Instead they will tend to concentrate their efforts on those (fewer) flowers per plant that are most in need of visitation, thus also being encouraged to move around between separate plants more often and to ensure outcrossing rather than selfing. Reasons for favoring breeding by outcrossing (i.e., with other plants) are covered more fully in chapter 3.

4. What Makes a Visitor into a Good Pollinator?

In many ways this is the crucial theme running through this book. It relates to what is probably the major current debate in pollination ecology, that is, to what extent pollination it is a generalist process and to what extent it is a specialist one. Pollination has in the past nearly always been categorized in terms of syndromes, with particular groups of flowers recognized as having particular sets of characteristics (of color and scent, shape, timing, reward, etc.) that suit them to be visited by particular kinds of animals; and it is implicit in this approach that these suites have often been arrived at and selected for by convergent evolution in plant families that are unrelated. Thus most authors have used terms such as ornithophily to describe the bird pollination syndrome, or psychophily for the butterfly pollination syndrome. Flower characteristics would be listed that fit each syndrome, and an unfamiliar flower’s probable pollinators could therefore be predicted. Flowers in each category were seen as having a degree of specialization that suited them to their particular visitors, with some syndromes being more specialized than others. Nearly all earlier works on pollination were organized around this theme of syndromes, and it served as a useful structure for understanding animal-flower interactions for nearly two centuries. Without knowing this background it would be nearly impossible to follow the current debates that are a major focus for pollination ecologists, and it would also be very difficult to structure the information on flower attractants and flower rewards in chapters 5–9. This book thus retains a syndrome-based approach throughout its early chapters and explicitly considers the evidence in support of a syndrome approach in chapter 11; then it unashamedly covers each of the syndromes in turn in chapters 12–19, providing all the core materials on whic...