![]()

PART ONE

INSPIRATION, REMEMORATION, REFORM

![]()

ONE

Remembering Islamization, 1300–1750

TO THE MOUNTAIN OF FIRE

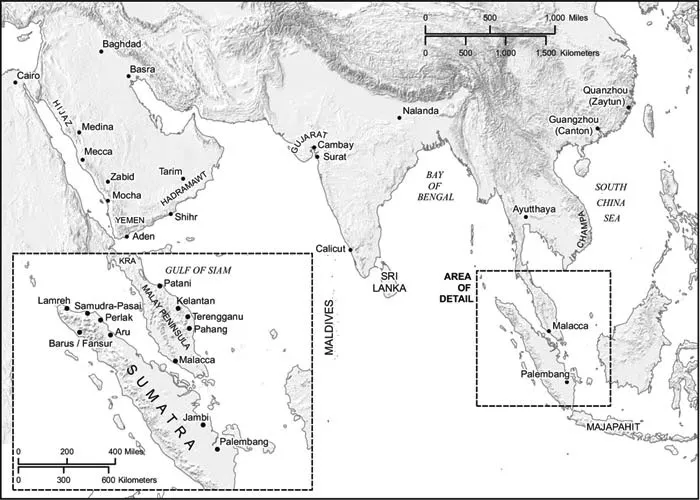

Seen from above, the great archipelagic world of Indonesia, the scene of much of what follows in this book, drifts eastward from the Bay of Bengal into the Pacific Ocean. The Malay Peninsula, too, has long been an integral part of this world. Its ports, and those of the mainland from the Gulf of Thailand to southern China, were tightly linked to states located on the major isles of Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas farther to the east. South of these islands, and sharing in that same nexus of trade, lie Java and such eastern islands as Bali, Lombok, and Sumbawa.

From the opening of the Common Era, the rulers of the western half of this world shared an Indianized court culture and profited from the presence of foreign traders. This is because Southeast Asia lies at the intersection of two trading zones of significant antiquity. The first encompassed the Indian Ocean while the other skirted the South China Sea; indeed our knowledge of some of the earliest Southeast Asian kingdoms comes from Chinese records that note the arrival of emissaries with seemingly Muslim names. From the other direction we have Arabic accounts of sailing routes from the Persian Gulf to the ports of Southern China that had the Malacca Strait as their fulcrum. There captains would await the change of monsoonal winds to carry them either onward with their journeys or back home, while the intra-archipelagic trade injected costly spices, gums, rare plumage, and aromatics into holds already brimming with fabrics, ceramics, and glassware.1

Though there are suggestions of early Muslim sojourners in the region, Islam was a late arrival as a religion of state. For much of the second half of the first millennium, the ports along the Malacca Strait seem to have paid tribute to the paramount estuarine polity of Srivijaya (or those states which claimed its inheritance). Based around the harbors of East Sumatra, Srivijaya’s rulers supported Mahayana Buddhism, making pious bequests as far afield as the monastery of Nalanda in Bihar, India, and sending missions to China by way of Guangzhou and, later, Quanzhou, the great southern port established under the Tang Dynasty (618–907). On the other hand, Arab accounts, which refer to Quanzhou as the ultimate destination of Zaytun, appear only vaguely aware of Srivijaya at best, and merely mention a great “Maharaja” who claimed the islands of a domain that they called “Zabaj.” Its capital was distinguished by a cosmopolitan harbor and an ever-simmering “mountain of fire” nearby.2

More mysterious still are the identities of Southeast Asia’s first established Muslim residents. In part this is a result of the successive rememorations of Islamization that seldom tally with the physical traces left in the soil. Marco Polo referred in his account of Sumatra (around 1292) to a new Muslim community founded by “Moorish” traders at Perlak, and one of the first dated Muslim tombstones (which gives the Gregorian equivalent of 1297) names “Malik al-Salih” as having been the contemporary ruler at the nearby port of Samudra-Pasai, but some see evidence of even earlier communities further west at Lamreh, where badly eroded grave markers suggest a connection both with Southern India and Southern China.3

Figure 1. Southeast Asia’s Malay Hubs, ca. 1200–1600.

While we know little of the mechanisms underlying their deposition, whether they were middlemen acting for the China trade or perhaps even the Chola kings of Southern India, by the early thirteenth century, the spice traders of Aden, in Yemen, had at last become aware of Muslims inhabiting a place they now called “Jawa.”

4 It also seems that, by the fourteenth century, the rulers of Samudra-Pasai were either competing or colluding with those of Bengal for the right to have their names invoked in Friday prayers in Calicut, where Jawis (as the peoples of Southeast Asia were known to Arabic speakers) often met Indian, Persian and Arab coreligionists.

5 Hints of a Muslim Jawa appear in the writings of an Aden-born mystic,

Abdallah b. As

ad al-Yafi

i (1298–1367), who devoted much of his life to recording the miracles of

Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (1077–1166), the Baghdadi saint adopted as their axial master by many

mystical fraternities. Known as

tariqas, by al-Yafi

i’s day these fraternities had evolved into groupings under the leadership of specially initiated teachers, or

shaykhs, who claim successive positions in an unbroken lineage or “pedigree” (

silsila) of teachers that extends back to the Prophet. Whatever their particular line of spiritual descent, whether of the Qadiriyya, which is traced back through

Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani, or the Naqshbandiyya of Baha’ al-Din Naqshband (1318–89), the tariqas provide instruction in the techniques of being mindful of God—whether through silent contemplation, spectacular dances, or self-mortifications—that are commonly termed “remembrance” (

dhikr). Perhaps one of the most famous forms of dhikr is the “Dabus” ritual favored by the Rifa

iyya order, which takes its name from the Iraqi Ahmad al-Rifa

i (d.1182), in which devotees seemingly pierce their breasts with awls without injury. By contrast other tariqas, such as branches of the Naqshbandiyya, are known for their silent contemplation. Regardless of the specific mode of dhikr, it is held that such activities, when led by a knowledgeable master, can generate ecstatic visions and moments of “revelation” in which the veils of mystery separating the believer from God are swept aside.

Writing in the fourteenth century, al-Yafi

i recalled that as a youth in Aden he had known a man who was especially adroit at such mystical communications. He had even inducted him into the Qadiriyya fraternity. This man was called Mas

ud al-Jawi; that is, Mas

ud the Jawi.

6 We would seem to have proof here of A. H. Johns’ famous theory of a link between trade and the spread of Islam to the archipelago at the hands of the tariqa shaykhs. But while al-Yafi

i’s works continue to play a role in the spread of the stories of

Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani in Southeast Asia, any local memory of this process, if it was occurring in Sumatra in the same way as it was occurring in Aden, is lacking. Instead we often have regal accounts of how the light of prophecy was drawn to the region. In several cases, an ancestral ruler is said to have met the Prophet in a dream, to have had his somnolent conversion recognized by a Meccan emissary, or else to have been visited by a foreign teacher able to heal a specific illness. Perhaps the most famous example is found in the

Hikayat Raja Pasai (The Romance of the Kings of Pasai), in which King Merah Silu (who would become the Malik al-Salih commemorated by the headstone of 1297), dreamt that the Prophet had spat in his mouth, thus enabling him to recite the Qur’an upon waking, much as the Persian-speaking

Abd al-Qadir had been rendered an eloquent speaker of Arabic in al-Yafi

i’s

Khulasat al-mafakhir (Summary of Prideworthy Acts).

7Merah Silu is further said to have received a shaykh from Mecca to validate his conversion, a story that might at first seem to point to some form of tariqa connection. However the emphasis on Meccan validation more likely reflects regal concerns with genealogies of power and a long-running fascination for that city as the eternal abode of the family of the Prophet. Perhaps the most famous of the many Malay royal lineages, Malacca’s Sulalat al-salatin (Pedigrees of the Sultans), incorporated sections of the Hikayat Raja Pasai and preempted the line of Muhammad by asserting that the dynastic founder had the blood of Alexander the Great.8

Regardless of how it was achieved or subsequently justified, Islamization brought the ...