![]()

II

THRESHOLDS

Summoning the Supernatural and the Sacred

Of the countless articulations that mark our lives, there are some few that remind us of our place among larger rhythms. In the face of these we are stilled with a sense of something greater than us, something that transcends the quotidian. Time adjusts accordingly.

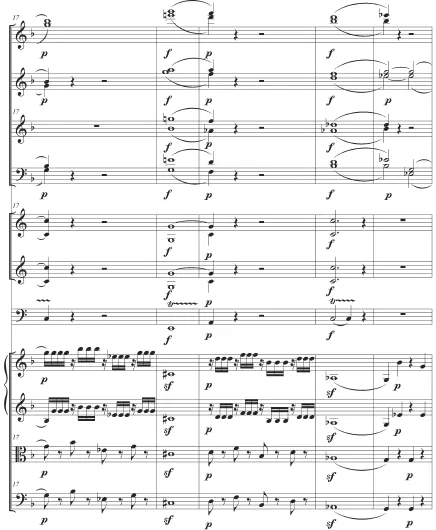

When Giovanni fatally wounds the Commendatore in the opening scene of Mozart’s

Don Giovanni, the turbulent music of their struggle suddenly gives way to a music of suspended animation (example 2.1). Mozart creates the stunned reaction to the Commendatore’s death out of the headlong immediacy of dramatic commotion. At its height, Giovanni’s fatal thrust pierces the Commendatore on an alarmed fermata, a diminished-seventh sonority from the nether side of the dominant of F minor (bar 175). This stroke culminates a staged fight, choreographed by the composer with upward lunges and rhythmic sword clashes. These almost mechanical gestures are supported upon a harmonic sequence that carries the opponents from Giovanni’s cadence in D minor downward to A, then G, then F, and further to a first-inversion B-flat sonority (A, D

, G, C

, F, B-flat

6). At this point the harmony changes course, and the upper line that has been descending bar by bar turns around, accelerating into the dominant of F minor and beyond, into Giovanni’s

coup de damnation on the diminished-seventh chord, a musical exclamation mark.

Everything changes after the fermata. The overheated thirty-second-note runs are gone; the sforzandi, gone; the downward stomping bass line, the harmonic aggression, all gone. In the hush of their absence, the awestruck trio of Giovanni, Leporello, and the dying Commendatore remains in place, singing lines that now seem to float within a new temporality. Pizzicato lower strings mark a slow pulse; violins run in place with triadic triplets—these small details sound with etched hyperreality, imprinted the way mundane details are when you hear the news that changes everything.1 A pedal point on the dominant of F minor holds things still.

Example 2.1 Don Giovanni, Act 1, Scene 1, bars 163–94

Each character reacts in his own way, with his own style of line. But Giovanni’s reaction is the most overtly lyrical, perhaps because he alone observes, while the others are busy communing with their own conditions. His is thus the overriding consciousness of the scene. Leporello’s stunned exclamations (twice mouthing the fatal diminished seventh) give way to his usual trembling patter. The dying Commendatore is reduced to gasps, his sustained A-natural in bar 187 a final flare of vitality before the last breath. This pitch carries the sound of tragic irony, brightly lifting away from F minor only to move upward into a subdominant trafficking morbidly with G-flats. After the Commendatore dies into the cadence, sinking half steps trace lines of somber destiny. They pass through the A-natural again but this time take it down through the A-flat rather than upward to the subdominant. The B-natural in the line is also drawn down, forgetting its usual upward move to the dominant. Thus the reflexes of life fall slack.

But the overall effect of this passage is not one of crushing anguish. There is no overbearing pathos here, nothing so heavy. Rather what meets the ear is a light, hovering texture. This lightness is a key to the experience. It constitutes what Mozart understood better than most. We have the rest of our days to measure and bear the full weight of a momentous revelation. But the revelation itself dispels the gravity of the mundane. Mozart allows us a liminal experience, by placing us on the threshold of the supernatural.

If the Commendatore’s death brings on the supernatural as the sudden absence of overbearing sound, the very beginning of the opera’s overture achieves a related effect with the sudden onset of such sound (example 2.2). For many listeners, the opening of this overture (bars 1–4) is one of the great shockers of the Viennese Classical era, right up there with the beginning of Beethoven’s Eroica. The harmony textbook is no help here, for it instructs us only that we hear a tonic followed by a dominant, as in any number of declamatory symphonic openings. It’s probably a given that a loud tonic minor at the beginning will always be arresting, but beyond that, how could such everyday ingredients create the effect of this opening, which is not just arresting but materializes with paralyzing immediacy, like the head of Medusa?2

As always, the scoring tells. We hear brass on the stentorian octaves D and A; winds on the full chords; upper strings syncopating against the basses’ implacable half notes, the last of which sustains beyond the upper voices. This single beat of remaining sound is the most frightening touch of all: to hear the bass emerge like this is to feel the menace, to realize that the terrifying face is looking at you.3

The half-step motion of the bass line is also crucial to the overall effect. Deploying the leading tone at the bottom of the dominant chord allows the fifth in the strings to work its own stark horror, while avoiding a parallel octave with the upper voice. The first inversion also makes for a less stable form of the dominant, which in turn attenuates the more standard effect of regal declamation of tonic and dominant. We hear the frightening mobility of power rather than the reassuring stability of power.

What follows is an insinuating echo of the opening, letting its enormity seep in slowly, quietly: beginning in bar 5, the winds twice repeat the D and A, now in descending octaves, while the lower strings present a slow chromatic descent to the dominant in dotted rhythms, ominous in their steadiness. When the pedal point on the dominant arrives in bar 11, anxiety mounts, with syncopated first violins quickly joined by the nervous sixteenth-note patter, Leporello-like, of the second violins. Striking harmonies ensue, in a more melodramatic styling—and then comes the extraordinary passage beginning at bar 23, which combines the dotted rhythms of bars 5–10 in the bass with the nervous sixteenth notes in the first violins. The harmonic progression alone is an effective example of tension-raising chromaticism, as each half step moves further from the brass pedal point on D. Trumpets and drums mark that D on each downbeat, not for ceremonial pomp, but rather as the sound of immovable fate. The D disappears only at the remarkable arrival of the E-flat chord in second inversion in bar 27. This has a clarifying effect at first (in that it clears the D out of the system while stopping the violin runs), then turns out to be only the advance staging of an augmented-sixth arrival on the dominant of D minor. But what makes this entire passage unforgettable are those violin scales—moving up then down, rising in half steps along with the bass and winds. Who would have thought to profile this drama of rising half steps against an interior pedal by filling each chromatic step with the banal utterance of an ascending or descending scale? And yet the effect is stunning. As though in a stupor, the violinists seem reduced to moving their fingers unconsciously, capable only of marking the rising half steps sounding around them on a kind of abacus of fear. This combination of unusual chromatic harmonies with the most common imaginable melodic pattern feels uncanny. Here again, we are faced with the hair-raising effect of liminal experience.

That first chilling step from D to E-flat which begins this chromatic ascent is echoed in the Molto Allegro, now as the sound of growing excitement, rising from D through D-sharp to E in the first violins. This move may also be heard as mockery of that frightening half step. After all, mockery of the fear of consequences is a leading trait of the Libertine; such jibes are the jangling spurs of his bravado. Don Giovanni raises these stakes, for he makes music of the fears of others, which may be what makes him the most charismatic of all the Don Juan incarnations. But that shared half step also reminds us that Giovanni’s merriment is borrowed from perdition. There’s an edgy boisterousness to this Allegro celebration, a simmering violence, as in those oft-recurring downward thrusts, many of which outline a tritone (e.g., bars 77 and following). We are not permitted to forget what stands behind it all: those sovereign chords of the opening, the once and future sound of abject damnation.

Example 2.2 Don Giovanni, Overture, bars 1–39

Don Giovanni wishes to live in a clamorous series of Nows, as though to shut out the sound of the past and future.4 But when past and future disappear, their reappearance—as embedded within the supratemporal realm of the Commendatore—is that much more momentous. Mozart’s opera stages this juxtaposition of supernatural time and human time, stages the boundary between Giovanni’s Now (his No to past and future), and the Commendatore’s Always. In the first-act death scene, we heard a fiercely Now moment cross over into a timeless moment. Similar crossings haunt this opera, which is made vivid by our abiding fascination—at times fearful, at time awestruck—with the supernatural, and with transgression. Transgression materializes the supernatural. Giovanni is the lightning rod that both mesmerizes the other human characters and draws down the taboo energy of ageless terror. The bolt strikes in the second-act finale, but its premonitory static electricity first prickles the air in those uncanny violin scales of the overture.

A much safer way to summon the supernatural is through the act of prayer. Mozart stages the act of prayer in the Confutatis movement of his Requiem, at the text “Oro supplex et acclinis, cor contritum quasi cinis, gere curam mei finis” (I pray, bowed and kneeling, my heart contrite, ashen: have a care for my end). The passage is remarkable in both its local and overall motions. It begins by shifting into a different realm (example 2.3). When the bass line reenters the musical texture at bar 25, after eight bars of women’s voices in suave counterpoint, it qui...