![]()

PART I

Foundations

![]()

1

Complementarity in Organizations

Erik Brynjolfsson and Paul Milgrom

1. Introduction

According to the American Heritage dictionary, a synergy is “the interaction of two or more agents or forces so that their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects” or “cooperative interaction among groups, especially among the acquired subsidiaries or merged parts of a corporation, that creates an enhanced combined effect.” Complementarity, as we use the term, is a near synonym for “synergy,” but it is set in a decisionmaking context and defined in Section 1.2 with mathematical precision.

Complementarity is an important concept in organizational analysis, because it offers an approach to explaining patterns of organizational practices, how they fit with particular business strategies, and why different organizations choose different patterns and strategies. The formal analysis of complementarity is based on studying the interactions among pairs of interrelated decisions. For example, consider a company that is evaluating a triple of decisions: (i) whether to adopt a strategy that requires implementing frequent changes in its technology, (ii) whether to invest in a flexibly trained workforce, and (iii) whether to give workers more discretion in the organization of their work. Suppose that more-flexibly trained workers can make better use of discretion and that more-flexibly trained and autonomous workers make it easier to implement new technologies effectively, because workers are more likely to know what to do and how to solve problems. Then, there is a complementarity between several pairs of decisions, which is characteristic of a system of complements. The theory of complementarities predicts that these practices will tend to cluster. An organization with one of the practices is more likely to have the others as well. Suppose an organization employs these three practices. Should this organization now adopt job protections, incentive pay, or both? The answer depends in part on the presence or absence of complementarities: if these new practices enhance worker cooperation with management in periods of technical change, then they, too, should be part of the same system.

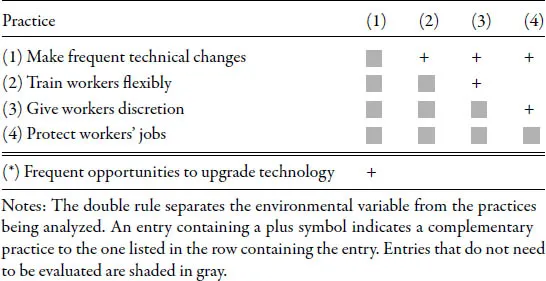

Table 1. Interactions in a system of complements

Often there is a related environmental variable that drives an entire system. In our example, suppose the organization operates in an environment that contains frequent, substantial opportunities to upgrade technology to save costs or improve products. Then it would be natural for the organization to favor the first practice—making frequent technical changes. Because of complementarities, this would in turn favor adopting the whole group of practices described above. The clustering of practices, the way choices depend on the environment, and the influence of each practice on the profitability of the others are all empirical propositions that we summarize with our example in Table 1.

Table 1 is a prototype for portraying and discussing the interactions in a system of complements. Each decision about a particular practice is labeled and appears in both a row and a column. We put the environmental variables in the rows below the double rule. In this case, there is just one: the frequency of valuable opportunities to upgrade technologies. To verify the system of complements, it suffices to check just the upper half of the table, because the complementarity relation is symmetric. Also, we can omit checking the diagonal entries, because complementarity is defined in terms of interactions among different decisions. The plus symbols in cells (1, 2) and (1, 3) of the table represent the complementarities that we have hypothesized as present between frequent technical changes and two other labor practices, while the plus in cell (2, 3) represents our hypothesis that flexibly trained workers use discretion more effectively than other workers do. Worker protection aligns workers’ long-term interests more closely with the firm’s interest, reducing resistance to change and enlisting workers in implementation. That accounts for the plus symbols in cells (1, 4) and (3, 4).

The plus in the last row indicates that the environmental variable directly favors one of the choices and, through the system of complements, indirectly favors all the others. We leave the cells blank when a priori we do not believe there to be a direct interaction. A version of this tool, called the “Matrix of Change,” has been used by managers and MBA students to analyze complementarities and thereby assess the feasibility, pace, scope, and location of organizational change efforts (Brynjolfsson et al. 1997).

1.1. Some Applications and Implications

Complementarity ideas can be usefully combined with ideas about the limits to coordination among separate firms to explore the scope of the firm. For example, in the early twentieth century, General Electric (GE) produced a wide array of products based on electric motors. Its intensive research into designing and producing electric motors complemented its strategy of producing a broad range of products using those motors. Improvements in the costs or capabilities of electric motors for one product line increased the probability of improvements for other product lines. Coordinating such variety in a single firm was favored by the concurrent development of a multidivisional organizational architecture.1

In addition, the analysis of complementarities can provide insights into organizational dynamics. For example, even when senior executives have a clear vision of a new strategy for a company, managing the change can be difficult or impossible (e.g., Argyris 1982; Siggelkow 2002b; Schein 2004).

Why is organizational change so difficult? Complementarities can provide part of the answer (Milgrom and Roberts 1990, 1992, 1995; Brynjolfsson et al. 1997). When many complementarities among practices exist in an established system, but practices from the established system and those from the new one conflict, then it is likely that the transition will be difficult, especially when decisions are decentralized. Because of the complementarities, changing only one practice, or a small set of them, is likely to reduce overall performance.2 The natural conclusion is that the organization should change all the practices in the new system simultaneously. However, making these changes all at once can be difficult or infeasible for at least three reasons.

First, there is a basic coordination problem. Actors who control different business practices, assets, markets, and strategies, including some that may be outside the direct control of the firm, need to coordinate on the scope, time, and content of the change. Furthermore, because the exact outcomes and optimal levels of each factor are likely to be at least partially unpredictable, these actors need to continue to agree to and coordinate on any additional adjustments and rent reallocations. All this effort requires accurate communication and an alignment of incentives.

Second, organizations inevitably consist not only of numerous explicit well-defined practices and choices but also many that are implicit or poor...