![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Cities and Regions in the Twenty-First Century: Why Do They Develop and Change?

Divergence and Turbulence

If the current residents of many countries were transported back just a few decades, they would not recognize many aspects of their cities and regions. This is paradoxical, since cities are durable structures made of concrete and steel, and in many ways, slow to change. The iconic dimensions of cities—Manhattan’s skyscrapers, Los Angeles’ long boulevards and freeways, and the historical core of Paris—stay with us. But many other dimensions of cities, from the granularity of their neighborhoods to the size and organization of entire metropolitan regions, and the map of winning and losing regions, change radically in small amounts of time.

In 1950, the average American would barely be glimpsing what would come to be the current “American way of life” in the suburbs and would not be paying much attention to what we now call the Sun Belt. In 1960, few were worried about the decline of dozens of major metropolitan areas in the Manufacturing Belt, and the average resident of Detroit gave nary a thought to the idea that their metropolitan region would be considered the poster child of failure several decades hence. Nor would many have imagined that Houston and Las Vegas would be considered big success stories soon thereafter.

As late as 1980, the average American was not thinking about the resurgence of certain cities in the Frost Belt, such as New York, Chicago, or Boston, as would occur in the 1990s, or the gentrification of their forlorn center-city neighborhoods. In the 1980s, few scholars thought about the rise of “world cities,” such as Hong Kong or Shanghai, or how London or Paris would or would not be in their ranks. Nor would the Parisian in 1950 be able to imagine the massive suburbanization of that region and thorough gentrification of central Paris, erasing most of its characteristic raucous rough parigot edges. The resident of Rio de Janeiro in 1940 would have laughed scornfully if presented with the prospect of São Paulo becoming Brazil’s as well as South America’s biggest, richest metropolitan area. The deck of economic development is constantly being reshuffled, and the cards are being dealt out over different places in an uneven and changing pattern.

Urbanization has been on a sharp upswing since the trade revolution that began with the age of exploration in the late 1400s. It intensified with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century. This period has also witnessed the “Great Divergence” at the global scale, whereby the West after 1750 left the rest of the planet behind in wealth and income. As part of this divergence, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the world’s big cities became its richest places, but some cities became a lot richer than others. In the merchant period, cities like Venice, or Xi’an at the other end of the Silk Road, found themselves losing out to Manchester in terms of wealth. The industrial period generated a patchwork of higher- and lower-income regions. The Industrial Belt of northern Europe first had the highest incomes, followed by the core regions of North America. In the Old Northeast of the United States, cities such as Buffalo and Cleveland were points of high wealth in 1900, especially when compared to Atlanta or Houston. The rise of California and the “first” New Economy in the early twentieth century added wealthy and growing city-regions on the Pacific coast to the ranks of the ten-richest large urban regions.

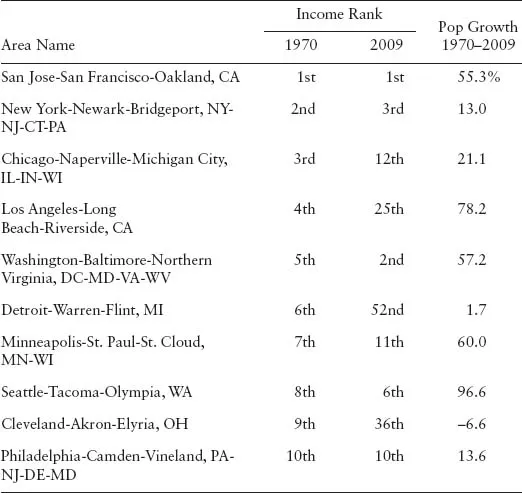

By the late 1960s, across Europe and North America, many of the formerly richest urban regions were losing employment and struggling to maintain their income levels. The change in the United States was particularly dramatic, as a host of Sun Belt cities not only grew bigger than old manufacturing cities but also grew richer (Kim 2002). Some of the old manufacturing cities even had absolute declines in employment. Though the US case is particularly marked, the same thing happened to European manufacturing cities such as Lille, Manchester, or Torino. This turbulence for the United States can be seen in table 1.1.

The late 1980s and 1990s brought further change in the West. Certain cities that had been written off as declining manufacturing centers, including New York and London, began to attract people again, and most dramatically, moved back up the urban income hierarchy as their economies were recomposed around high-paying New Economy industries and jobs. Indeed around the world, a set of major urban regions started to resemble one another and became essential switching points of the emerging global economy. Hong Kong, Tokyo, Singapore, São Paulo, Sydney, Toronto, Zurich, and many other cities grew bigger and richer, while many formerly rich, mostly middle-size industrial cities lagged them more and more. With the increase in global trade and integration, major industrial cities in developing countries, especially China, kept attracting people yet also moving up the world income hierarchy of cities; Guangzhou, Belo Horizonte, Bangalore, Johannesburg, and Kuala Lumpur are just a few of these places. Reflecting this reality, Richard Dobbs and his colleagues (2011) show that the six hundred largest cities in the world house about a third of the global output, and two thousand urban centers produce the majority.

TABLE 1.1

U.S. Consolidated Statistical Areas with 1970 Population Greater Than 2 Million, Ranked According to Per Capita Personal Income Levels

NOTE: Bureau of Economic Affairs REIS data.

In addition to this broad picture of urbanization, metropolitan areas are continuing to spread out physically. The great suburban wave in the West is slowing, but suburbanization is gaining in emerging economies, perhaps with a slight nod to environmental concerns that push for greater density and more collective transport—although it is unlikely to be abandoned. Many metropolitan areas in the twenty-first century will expand not only through greater employment density in their core but also by replicating the polycentric metropolitan region model that is already found in Los Angeles, London, Paris, São Paulo, Mexico, and San Francisco.

Thus, within this shared global process of development, the pattern of development will remain territorially unequal. There are two senses of such inequality. The first is that urbanization is itself a form of extreme unevenness: it packs people, firms, information, and wealth into small territories. About 40 percent of US employment is located on 1.5 percent of the country’s land, and about 60 percent is situated on 12.5 percent of the land. In most countries, this has led in recent years to an increase in income divergence between major metropolitan areas and the remaining parts of the national territory. Some of this is offset through income transfer to those areas, but the basic dynamic—of a split between the middle- and large-size metro areas and the rest—will likely characterize development in the opening decades of the twenty-first century. The second type of unevenness of development is that individual metropolitan regions, over the medium run of thirty to forty years, undergo considerable turbulence in their fates, rising and falling in the income ranks, and gaining or losing population at different rates.

City-regions are the principal scale at which people experience lived reality. The geographical churn, turbulence, and unevenness of development, combined with the sheer scale of urbanization, will make city-region development more important than ever—to economics, politics, our global mood, and our welfare. And managing it will pose one of the most critical challenges to humanity. The winning side of the process will excite us and motivate talent, but the losing side will create displacement and anger, both within and between countries.

Growth and Change: The Challenge to Theory and Evidence

Social science has paid abundant attention to describing urban growth and change—or more broadly, to the regional and geographical dimensions of growth and change. Notwithstanding the progress that has been made, we are still far away from identifying the causes of such change. Change and its causes are what matter most to human welfare. The big game to be hunted is insights into the drivers of changes in the geography of economic development and population. The problem is that we still mostly account for patterns in a post hoc manner, or attribute causes to them by oversimplifying, thus bracketing out most of the interesting interactions (“if this, then that” kinds of approaches).

Explaining the growth and change of regions and cities is one of the great challenges for social science (Perloff 1963). Cities or regions, like any other geographical scale of the economic system, have complex economic development processes that are shaped by an almost-infinite range of forces. The thorny question is, What should social science aim to do in the face of such complexity? It would be unrealistic to ask any field of theory and research—especially in an area of such complex human-technical interaction as the spatial economy—to meet all these challenges fully. But a focus on change and causality, by which I mean studying cities and regions as forward-moving development processes—should determine what is most relevant in defining the ambitions of the field. Concretely, then, the field should be able to respond to such questions as: Why do city-regions grow? Why do some decline? What differentiates city-regions that are able to sustain growth from those that are not? What are the forces that cause per capita income to converge or diverge, and under what conditions do they operate? Why are some city-regions so much more productive than others? What is the relationship of a region’s material-physical structure to its economic performance? What are the principal regularities in urban and regional growth, and what are the events and processes that are not temporally or geographically regular but instead affect pathways of development in irreversible ways?

Urban and regional development is a noisy and complex phenomenon. Its most significant causes cannot be understood through the tools of any single discipline or theory, even the “economic” ones. This book’s main purpose is to consider the explanations we use for city and regional growth and development, and organize the major questions along with the toolbox we have for attempting to answer them. It draws principally from economics, economic geography, and economic sociology. Four contexts of the development of city-regions compose the toolbox for explanation that this book constructs: economic, institutional, social interaction, and political or normative. In each context, I focus on identifying microfoundations: how individuals, households, firms, and groups interact to make cities and change them.

Economics and Geography

I begin with the task for economics and then move on to the other disciplines. The geography of uneven economic development is the central concern of development economics, economic geography, and regional science and urban economics. This book engages with all these fields. The main difference that characterizes studying the mechanisms of development at the urban-regional scale from the national scale has to do with the degree of openness of the economies in question. International flows of goods, people, capital, and information are important to national development, and arguably ever more so in a period of intense globalization such as the present one. But there are still many significant limits to openness. Nation-states have sovereign state structures with powerful tools to shape development. These include property rights, fiscal and monetary policy, the ability to intervene in the economy’s supply of factors through education, border controls as well as research and development (R & D) and tax policy. In addition, countries have informal institutions such as common languages, traditions, and social and economic networks. This allows countries to limit their degrees and types of openness in a wide variety of ways.

City-regions within a country do not have that kind of sovereignty or separation. There are fewer barriers to trade as well as the mobility of firms, capital, and people inside national economies than in the global system as a whole. City-regions also have limited fiscal capacities compared to nation-states and no independent monetary policy. City and regional governments do not set fundamental laws about such things as property rights, tax policy, and other basic institutional issues. In some countries, there are local education systems, but they usually depend on national norms and, often, national budgets. R & D may be more intense in some regions than others, but its basic structure and magnitudes are strongly shaped by national policy. In a few countries such as Spain, Belgium, or Switzerland, the social and economic networks are sharply segmented by language and history. In most countries, though, the national language and culture have strong unifying influences on city-regions.

In standard economic models of regional development, this high degree of openness is captured by assuming the unlimited mobility of labor (people) and capital (firms), and low trade costs for goods and services (output) between regions. In these approaches, we thus assume high openness and low costs of interaction with other regions, allowing research to turn to what we might call patterns of “sorting” of firms and people. This means that urban and regional economics tends to reduce the question of regional development to the interregional economics of the sorting of capital and labor. In part I of this book, I argue that standard urban and regional economics attributes too much importance to sorting, and that it gets the principal sources of sorting wrong. Whereas standard urban and regional economics sees sorting as driven principally by costs of living, housing markets, and local business climates, I see it as driven principally by changes in technology and trade costs.

International development studies, by contrast, identifies concerns that should be at the heart of analyzing city-region development. Since countries have significant barriers to trade and factor mobility, development is structured not just by what is sorted to them but also by what they do internally with the resources they have and create (Helpman 2011). Regional development—like national development—is strongly influenced by interaction processes within the economy—notably in innovation, know-how, human networks, labor markets, and local Social Interaction and political processes related to development. These internal developmental dynamics of the productive economy in turn contribute to sorting, in a two-way interaction between the local and other scales of the economy.

The location of the leading-edge tradable activities of the economy—in shorthand, the “innovation sector”—is not just a sorting response to factor costs and factor prices. In many ways it is the other way around. Regional business ecosystems or clusters generate or attract their own factor supplies, and create their institutional and interaction environments. These conditions cannot be readily imitated, nor can their costs or prices be bid down through interregional competition and sorting of firms and people.

Geographers, sociologists, and many students of urban politics typically concentrate on these internal dynamics of regions. Unfortunately, these scholars inhabit separate worlds of academic and policy debate from those explored principally by economists. The disciplines of geography, sociology, and urban politics think about how business networks affect entrepreneurship and specialization; how politics affect local labor markets and wages; how social networks influence political attention and problem solving; how ideas, traditions, and cultures impact the environment for firms; and how land use is shaped by many such local forces. All these contribute to the internal developmental dynamics of city-regions, and they differ strongly from city to city.

The Book

For the noisy and complex problem identified above, there will be no single “big-bang” model, but rather four analytic contexts, covering several disciplines: again, economic, institutional, innovation or interaction, and political or societal.

The economic context explored in chapters 2 through 5 concerns the geography of production, or where firms and jobs go, and the geography of individual household and worker locational choices. In chapter 2, I ask whether it is movements of people seeking quality of life or jobs/firms seeking production locations that set off major sequences of change in urban and regional development. The response is that city-regions develop mostly as workshops of firms, not playgrounds of individuals. In chapter 3, I discuss why industries concentrate in general, and what kind of spatial-economic pattern of population and production they trace out. In chapter 4, I look at why some cities and regions have prices and wages that are so much higher than others, and how this fits into the overall economic process of wealth creation.

In chapter 5, I consider the role of individuals and their preferences for where to live; for firms, I examine their preferences for where to locate; and for both, I look at their preferences for public goods. Any broad economic process such as city-region development is the result of innumerable individual choices. A critical issue in all studies of urban development is the extent to which the pattern of urbanization responds to such preferences. I will argue that the relationship between preferences and urban outcomes is fraught with tensions. This means that we can only rarely use the characteristics of existing cities and urban systems to deduce “what people want,” or what they would “prefer to prefer.”

For economists, this book attempts to occupy a middle ground of respect for the technical workings of theory, although using mostly words and stories to communicate, with some numbers and models (Leamer 2012). The goal is not to build models but instead to find a framework for the economics of cities and regions that captures the main forces of their development.

The principal economic models take us a long way, but cannot fully explain the selectivity of dev...