![]()

1

Leathery-Winged Harpies

If TV, film, and overzealous internet users have taught me anything, it’s that the prehistoric world was harsh and brutal, and everyday existence was a life-or-death struggle. These terrible landscapes would be unrecognizable to our modern eyes, and only the biggest, nastiest animals survived. Consider, for example, the giant birds that stalked the Earth as recently as two million years ago. Taller than basketball players, they kicked and stabbed small, defenseless mammals to death. The ancestors of our pet cats and dogs wielded sabre teeth and bone-crushing jaws that they used to hunt giant elephants and rhinoceros, themselves armed with tusks and horns that would shame their mightiest modern relatives. The world was even more ferocious before these birds and mammals existed. During the span of time known as the Mesozoic (245–65 million years ago, or “Ma”), terrible reptiles ruled the day and predator-prey arms races were more intense than the Cold War. Gangs of carnivorous dinosaurs attacked their enormous herbivorous relatives, contesting their switchblade claws and armor-piercing teeth against the spikes, clubs, shields, and armored hides of their quarry. The Mesozoic oceans were just as deadly, teeming with giant, snaggle-toothed marine reptiles that render Moby Dick as intimidating as Flipper. Even the planet itself had a bad attitude in this Age of Reptiles. Angry volcanoes perpetually smoked, continents ripped themselves to pieces, and gigantic meteorites collided with the Earth, thowing enough dust and ash into the skies to block out the sun and cause cataclysmic extinction events.

The skies of this terrible age were no less formidable. They were dominated by a group of lanky grotesques, strange hybrids of birds and bats with a decidedly reptilian flavor. Their oversize heads were bristling with ferocious teeth or else bore savage beaks, each used to spear fish from primordial seas. Their outstretched membranous wings attained dimensions rivaling the wingspans of small aircraft, but were supported by lank, undermuscled limbs and tiny bodies. They were weak, flimsy, and pathetic animals, barely able to power their own locomotion and reliant on cliffs and headwinds to achieve flight. They were virtually helpless when grounded, barely able to push or drag themselves about, and completely at the mercy of any carnivorous reptile that fancied chewing on their hollow, twiglet-like bones. These creaky beasts were an archaic first attempt by vertebrate animals to achieve flight before graceful birds and nimble bats inherited the skies later in Earth’s history. Given their obvious physical ineptitude, it’s hardly surprising these creatures, the pterosaurs, collectively bought the farm at the end of the Mesozoic, along with any dinosaur that was not lucky enough to have evolved into a bird.

But That’s All Hokum

Of course, the world and animals described above are nothing but caricatures of reality, the sort of landscape you may expect to find in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World or similar-grade fiction. The popular view of primordial Earth as violent and totally unfamiliar is probably entirely untrue, a construct of poor scientific communication, overdramatic media representation, and romantic storytellers. In reality, ancient animals were no less sophisticated or intelligent, nor more freakish and savage, than those alive today. Paleontological research has probed deeply into the exotic and strange natures of many ancient animals to reveal that they merely represent “extreme” variants of anatomies and behaviors we see in our modern, familiar species. Such research has not made animals like the long-necked sauropods or giant theropod dinosaurs any less spectacular, but they are certainly not as mysterious and enigmatic as they once were.

Pterosaurs, which translates from Greek to “winged lizards,” have suffered more than most in their depiction as ancient savages. All that remains of these animals are their fossil bones, oddly proportioned skeletons that have proved difficult to comprehend and continue to cause frequent controversies among those who study them. The pterosaur’s ability to fly, combined with bizarre anatomy, often gigantic size, and an old-fashioned attitude that extinct animals were inherently inferior to modern species, resulted in them being perceived as crude, biological hang gliders, which were rather useless at everything but remaining airborne. Constant, often unwarranted, comparisons with birds and bats has cast pterosaurs as evolutionary also-rans, vertebrates that took the bold first stab at powered flight but were ultimately only the warm-up act for later, more sophisticated fliers.

FIG. 1.1. Two Rhamphorhynchus, fish-eating pterosaurs of the Late Jurassic, doing what pterosaurs do best.

FIG. 1.2. The major pterosaur bauplans of the 130–150 species currently known. See chapters 9–25 for the identities of each animal.

Thankfully, these attitudes have slowly changed. Most modern pterosaurologists perceive pterosaurs as successful, diverse animals with interesting and intricate life histories, and in this book we’ll discover the evidence for this change in attitude. We’ll see that, while pterosaurs were undeniably very well adapted for powered flight (fig. 1.1), they were also skilled walkers, runners, and swimmers. They lived in diverse habitats across the globe and fueled their active lifestyles with prey caught in distinct, dynamic ways. They grew from precocial beginnings to adulthood and invested heavily in social and sexual display before becoming old and, in some cases, sick and arthritic. We’ll meet numerous pterosaur groups (fig. 1.2) and over one hundred species spread across a dynasty spanning almost the entire Mesozoic, beginning in the Triassic period (245–205 Ma), thriving in the Jurassic (205–145 Ma), before ending at the very end of the Cretaceous, 65 Ma.

Our overview of pterosaurs is split into three parts. We’ll start with an assessment of their general paleo-biology, looking at their anatomy, locomotion, and other generalities of their lifestyles. Then, beginning with chapter 9, we’ll meet, chapter by chapter, the diverse array of pterosaur groups currently recognized by pterosaur researchers, or “pterosaurologists.” Finally, in the last chapter, we’ll ponder their evolutionary story and try to ascertain why the skies of modern times are not full of membranous, reptilian wings in the way they once were.

![]()

2

Understanding the Flying Reptiles

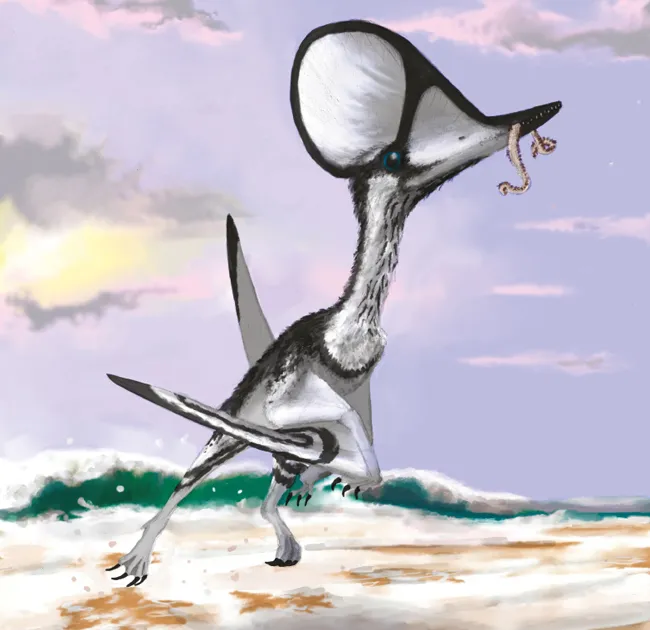

FIG. 2.1. A modern reconstruction of the first pterosaur known to science, the ctenochasmatoid Pterodactylus antiquus. Although known since 1784, many details of its anatomy, including its headcrest, keratinous beak tips, and webbed feet, were not found in fossils until this century.

Pterosaurs have a track record of being a rather difficult group of animals to study. Since their discovery well over two centuries ago, they have frequently confounded attempts to comprehend their relationships to other animals (chapter 3), their terrestrial locomotion (chapter 7), or even simply parts of their anatomy (chapters 4 and 5). The history of these specific aspects of pterosaur research will be covered in subsequent chapters but, before we get to these, we will take a moment to familiarize ourselves with a broad outline of the first 230 years of pterosaur studies. In addition to the subsequent chapters offered here, readers particularly interested in the history of pterosaur research may enjoy the excellent discourses on this topic by the godfather of modern pterosaurology, Peter Wellnhofer (1991a, 2008). As we’ll see below, Wellnhofer almost single-handedly revolutionized pterosaur research and laid the foundations for our modern understanding of these animals. He also provided a critical link between the three main ages of pterosaur paleontology, which can be roughly divided into the fruitful 1800s, a slump in the middle of the twentieth century, and our current golden age of pterosaurology.

1700–1900: Discovery After Discovery, Revelation After Revelation

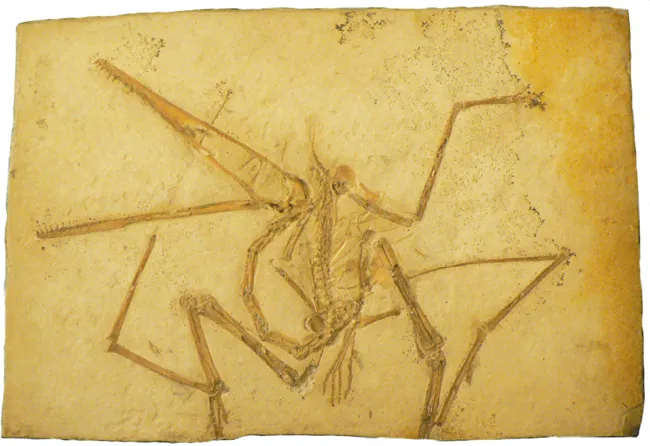

The first pterosaur fossil, an exquisitely preserved, complete skeleton of an animal that would later be called Pterodactylus (figs. 2.1 and 2.2; also see chapter 19), was found at some point between 1767 and 1784 in the world famous Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone of Germany, the same deposit that would later yield the famous fossil bird Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer 1991a). The skeleton was brought to the attention of the Italian naturalist Cosimo Collini. Despite careful study, he remained unsure about the nature of the fossil. He thought the specimen represented a petrified amphibious creature, and suggested that the long fourth digit on each hand may have represented the spar of a flipper. Collini published his illustration and description of the fossil in 1784, the first documentation of a pterosaur in scientific literature. His work was soon noticed by the most eminent natural historian and comparative anatomist of the time, Baron Georges Cuvier. Cuvier’s tremendous knowledge of animal form enabled him to see through the alien nature of the remains, and he realized from Collini’s illustration that the elongate fourth finger was not a flipper at all, but the supporting strut of a membranous wing on an ancient, flighted, and reptilian creature (Cuvier 1801; see Taquet and Padian 2004 for details).

FIG. 2.2. The first pterosaur fossil known to science, a complete specimen of the Jurassic species Pterodactylus antiquus. Photograph courtesy of Helmut Tischlinger (specimen housed in the Bavarian State Collection of Palaeontology and Geology, Munich; used with permission).

It is hard for us to imagine how significant Collini’s Pterodactylus was to those originally studying it. Far from just revealing the existence of pterosaurs, this animal was also strong evidence for a concept that was once considered radical by even the most eminent nineteenth century researchers: extinction. Most fossils known at that point were the remains of marine animals that, although never seen by humans, may have still existed in unexplored depths of the oceans. Collini’s pterosaur, by contrast, was a relatively large, conspicuous creature that would live in our own realm if it existed today. This distinctive creature, as well as several other newly discovered, large, terrestrial fossil vertebrates, had never been witnessed in the surveyed parts of the world, forcing scholars like Collini and Cuvier to grapple with, and eventually accept, the concepts of life before human history and extinction (Taquet and Padian 2004). These ideas were only some of the heretical concepts proposed in what we now term the Age of Enlightenment, a century-long period in which eighteenth-century researchers began to place empirical observations and data before the religious doctrine that had previously been used to explain the natural world. Thus, our introduction to pterosaurs coincided with a rich period of scientific discovery, making them an integral part of the foundations of paleontology and geology.

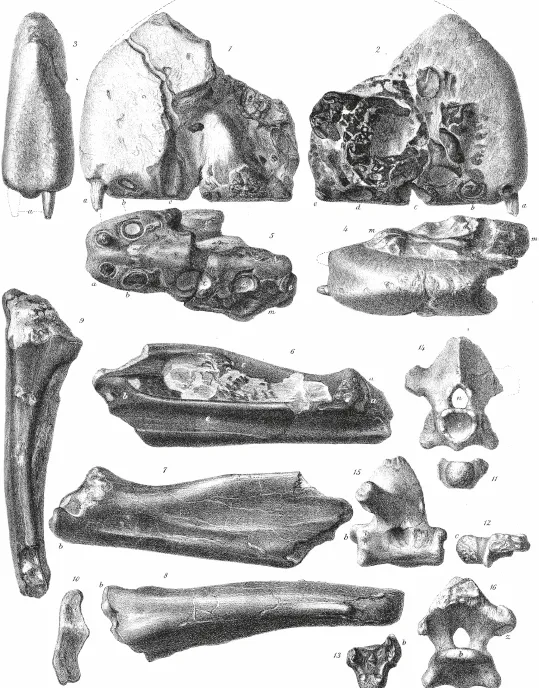

FIG. 2.3. One of many exceptional hand-drawn plates from Richard Owen’s 1861 Palaeontographical Society monograph on Cretaceous reptiles, portraying the fragmentary pterosaur remains from the British Cambridge Greensand (see chapter 16 for more on these deposits). Owen authored numerous pterosaur monographs in his career, all of them illustrated with similarly excellent draftsmanship.

Spurred on by a new understanding of the world, nineteenth-century investigators were prolific in their documentation and analysis of pterosaur fossils, although it was the middle of the nineteenth century before Cuvier’s reptilian identification of pterosaurs was fully accepted. Fossils of new pterosaurs were being found across southern Germany and in other parts of Europe (e.g., Buckland 1829) and by the late 1800s, they were uncovered in the newly opened and fossil-rich deposits of North America (Marsh 1871). Much of the pterosaur material available to these Victorian investigators was rather scrappy, and following the once fashionable idea that every slight difference among fossil specimens was of taxonomic significance, dozens of pterosaur species were named that are of dubious validity to our modern eyes. Pterosaurologists are still struggling with the fallout of this overzealous naming, but by way of redeeming themselves, many Victorian paleontologists were also extremely skilled at describing and illustrating their pterosaur specimens (fig. 2.3). Thus, over one hundred years on, their work remains relevant and valuable to modern researchers, and is still cited heavily in modern li...