eBook - ePub

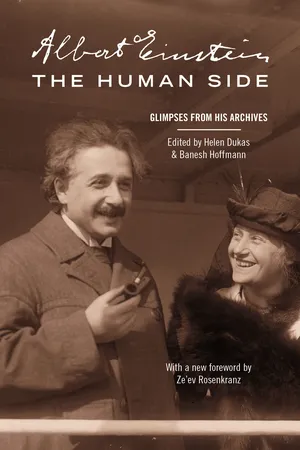

Albert Einstein, The Human Side

Glimpses from His Archives

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Albert Einstein, The Human Side

Glimpses from His Archives

About this book

Modesty, humor, compassion, and wisdom are the traits most evident in this illuminating selection of personal papers from the Albert Einstein Archives. The illustrious physicist wrote as thoughtfully to an Ohio fifth-grader, distressed by her discovery that scientists classify humans as animals, as to a Colorado banker who asked whether Einstein believed in a personal God. Witty rhymes, an exchange with Queen Elizabeth of Belgium about fine music, and expressions of his devotion to Zionism are but some of the highlights found in this warm and enriching book.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Princeton University PressYear

2013Print ISBN

9780691023687, 9780691082318eBook ISBN

9781400848126ALBERT EINSTEIN was not only the greatest scientist of his time but also by far the most famous. Moreover, he answered letters. And it is this combination that makes the present book possible.

Unlike our previous book, Albert Einstein: Creator and Rebel, this one is not a biography and does not explain Einstein’s ideas. It has no chapters, no table of contents, no index, and, at first glance, no plan or structure. It consists, for the most part, of quotations from hitherto unpublished letters and the like that Einstein wrote without thought of publication. There is no need to describe them further here since they speak eloquently for themselves.

Some of the items were sent out in impeccable English, and these we have quoted verbatim. Other items were issued in less idiomatic English, and in presenting them we have made occasional minor changes while preserving the Germanic flavor that gives them charm. All other items are presented in English translation. Often an item that was issued in English was based on a German draft that still exists, and in such cases we have given the English version that was actually sent instead of making an independent translation.

Einstein was an artist not only in his science, which had a transcendent beauty, but also in his use of words. In the latter part of this book, therefore, we have included the original German versions or German drafts, whenever available, so that the reader acquainted with the language can savor Einstein’s prose at first hand.

The quest for peace was an important part of Einstein’s life. Indeed, a whole book, Einstein on Peace (New York, Schocken Books) has been devoted to the subject, and so thorough is its coverage that hardly a scrap of unpublished material on the topic was left over for us to quote. Therefore, for details of this facet of Einstein we refer the reader to that book. We have, however, quoted a lengthy item from the book. Its inclusion has a twofold justification: it is a powerful statement in its own right with a special publication status: and its presence has a symbolic significance as a token salute to all the other items in Einstein on Peace that we were sorely tempted to republish here.

The order of presentation of the items is not haphazard. It is akin to that of crowding recollections of a rich life, each sequence apt to take unexpected turns as memory, with a logic all its own, leaps from remembrance to linked remembrance back and forth over the years. In this book there are several such sequences, their starts usually indicated by a more pronounced gap than usual between items. Each item may be taken by itself. But the book is intended to be read as a whole: it offers a seemingly rambling sightseeing journey whose cumulative effect, we hope, will be a deeper and richer understanding of Einstein the man.

For those who would like a road map, we have included a brief Einstein chronology at the end of the book.

IN a book about Einstein it is not inappropriate to begin with an item that breaks three rules simultaneously: First, it concerns a letter that Einstein did not answer; second, the presentation makes use of footnotes; and third, the item itself has been published before.

In the summer of 1952 Carl Seelig, an early biographer of Einstein, wrote to him asking for details about his first honorary doctoral degree. In his reply Einstein told of events that occurred in 1909, when Einstein was earning his living at the Swiss patent office in Bern, even though he had propounded his special theory of relativity four years earlier. In the summer of 1909 the University of Geneva bestowed over a hundred honorary degrees in celebration of the 350th anniversary of its founding by Calvin. Here is what Einstein wrote:

One day I received in the Patent Office in Bern a large envelope out of which there came a sheet of distinguished paper. On it, in picturesque type (I even believe it was in Latin*) was printed something that seemed to me impersonal and of little interest. So right away it went into the official wastepaper basket. Later, I learned that it was an invitation to the Calvin festivities and was also an announcement that I was to receive an honorary doctorate from the Geneva University.** Evidently the people at the university interpreted my silence correctly and turned to my friend and student Lucien Chavan, who came from Geneva but was living in Bern. He persuaded me to go to Geneva because it was practically unavoidable—but he did not elaborate further.

So I travelled there on the appointed day and, in the evening in the restaurant of the inn where we were staying, met some Zurich professors. … Each of them now told in what capacity he was there. As I remained silent I was asked that question and had to confess that I had not the slightest idea. However, the others knew all about it and let me in on the secret. The next day I was supposed to march in the academic procession. But I had with me only my straw hat and my everyday suit. My proposal that I stay away was categorically rejected, and the festivities turned out to be quite funny so far as my participation was concerned.

The celebration ended with the most opulent banquet that I have ever attended in all my life. So I said to a Genevan patrician who sat next to me, “Do you know what Calvin would have done if he were still here?” When he said no and asked what I thought, I said, “He would have erected a large pyre and had us all burned because of sinful gluttony.” The man uttered not another word, and with this ends my recollection of that memorable celebration.

In late 1936 the Bern Scientific Society sent Einstein a diploma that had just been awarded to him. On 4 January he wrote back from Princeton as follows:

You can hardly imagine how delighted I was, and am, that the Bern Scientific Society has so kindly remembered me. It was, as it were, a message from the days of my long-vanished youth. The cosy and stimulating evenings come back to mind once more and especially the often quite wonderful comments that Professor Sahli [Salis?], of internal medicine, used to make about the lectures. I have had the document framed right away and it is the only one of all such tokens of recognition that hangs in my study. It is a memento of my time in Bern and of my friends there.

I ask you to convey my cordial thanks to the members of the Society and to tell them how greatly I appreciate the kindness they have shown me.

A word of amplification is in order: When the document arrived, Einstein said, “This one I want framed and on my wall, because they used to scoff at me and my ideas.” Of course, he received numerous other awards. But he did not frame them and hang them on his walls. Instead he hid them away in a corner that he called the “boasting corner” [“Protzenecke”].

__________

In Berlin in 1915, in the midst of World War I, Einstein completed his masterpiece, the general theory of relativity. It not only generalized his special theory of relativity but also provided a new theory of gravitation. Among other things, it predicted the gravitational bending of light rays, which was confirmed by British scientists, notably Arthur Eddington, during an eclipse in 1919. When the confirmation was officially announced, worldwide fame came to Einstein overnight. He never did understand it. That Christmas, writing to his friend Heinrich Zangger in Zurich, he said in part:

With fame I become more and more stupid, which, of course, is a very common phenomenon. There is far too great a disproportion between what one is and what others think one is, or at least what they say they think one is. But one has to take it all with good humor.

__________

Einstein’s fame endured, and brought an extraordinary assortment of mail. For example, a student in Washington, D.C., wrote to him on 3 January 1943 mentioning among other things that she was a little below average in mathematics and had to work at it harder than most of her friends.

Replying in English from Princeton on 7 January 1943, Einstein wrote in part as follows:

Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics; I can assure you that mine are still greater.

__________

Back in 1895, after a year away from school, young Einstein became a student at the Swiss Cantonal School of Argau in the town of Aarau. On 7 November 1896 he sent the following vita to the Argau authorities:

I was born on 14 March 1879 in Ulm and, when one year old, came to Munich, where I remained till the winter of 1894–95. There I attended the elementary school and the Luitpold secondary school up to but not including the seventh class. Then, till the autumn of last year, I lived in Milan, where I continued my studies on my own. Since last autumn I have attended the Cantonal School in Aarau, and I now take the liberty of presenting myself for the graduation examination. I then plan to study mathematics and physics in the sixth division of the Federal Polytechnic Institute.

__________

Many years later Einstein, now famous, had occasion to prepare another vita. It has some interesting aspects.

Founded in 1652 in the town of Halle was the Kaiser Leopold German Academy of Scientists, in which Goethe had once held membership. On 17 March 1932, in memory of the hundredth anniversary of Goethe’s death, the Academy voted to invite Einstein to become a member. When Einstein accepted, the president of the Academy—in accordance with ancient tradition—sent him a biographical questionnaire with nine basic questions. Since space was scarce, Einstein answered in somewhat telegraphic style.

Although the Nazis had not yet come to power, their anti-Semitic propaganda was blatant. Einstein’s response to the first question is thus of particular interest. It reads as follows (italics added):

I. I was born, the son of Jewish parents, on 14 March 1879 in Ulm. My father was a merchant, moved shortly after my birth to Munich, in 1893 to Italy, where he remained till his death (1902). I have no brother, but a sister, who lives in Italy.

The second and third questions asked for details of his youth and education, which he dutifully supplied. The fourth question asked about his career. He responded as follows:

IV. From 1900 to 1902 I was in Switzerland as a private tutor, also for a while employed as house tutor and acquired Swiss citizenship. 1902–09 I was employed as expert (examiner) at the Federal Patent Office, 1909–11 as assistant professor at Zurich University. 1911–12 I was professor of theoretical physics at the Prague University, 1912–14 at the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich also as professor of theoretical physics. Since 1914 I have been a salaried member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin and can devote myself exclusively to scientific research work.

The fifth question asked about his achievements and publications. Some of the dates in his answer are puzzling. For example, the special theory of relativity certainly belongs to 1905 and not 1906, and the general theory of relativity to 1915 and not 1916. It is quite possible that Einstein was answering from memory and his memory played tricks on him. Here is what he wrote:

V. My publications consist almost entirely of short papers in physics, most of which have appeared in the Annalen der Physik and the Proceedings of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. The most important have to do with the following topics:

Brownian Motion (1905)

Theory of Planck’s formula and Light Quanta (1905, 1917)

Special Relativity and the Mass of Energy (1906)

General Relativity 1916 and later.

In addition mention should be made of papers on the thermal fluctuations, as also a [1931] paper, written with Prof. W. Mayer, on the unified nature of gravitation and electricity.

The sixth question asked about scientific travels. He responded as follows:

VI. Occasional lecture trips to France, Japan, Argentina, England, the United States, which—except for the journeys to Pasadena—did not actually serve research purposes.

The seventh question asked about the goals of his work. He replied:

VII. The real goal of my research has always been the simplification and unification of the system of theoretical physics. I attained this goal satisfactorily for macroscopic phenomena, but not for the phenomena of quanta and atomic structure. I believe that, despite considerable success, the modern quantum theory is also still far from a satisfactory solution of the latter group of problems.

The eighth question asked about honors that he had received. He answered as follows:

VIII. I became a member of many, many scientific societies, and several medals were awarded me, also a sort of visiting professorship at the University of Leiden. I have a similar relationship with Oxford University (Christ Church College).

What is extraordinary here is Einstein’s failure to mention his 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics. Surely it cannot be ascribed to faulty memory...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword to the 2013 Paperback Edition

- Publisher’s Preface

- Dedication Page

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- German Originals

- Einstein: A Brief Chronology

- Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Albert Einstein, The Human Side by Albert Einstein, Helen Dukas,Banesh Hoffman, Helen Dukas, Banesh Hoffmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.