![]()

CHAPTER 1

Music and the Brain

An Evolutionary Context

We are a species bound by evolution and diverse forms of change, both symbolic and social. Language and music are as much a part of our evolutionary development as the tool making and the cognitive skills that we traditionally focus on when we think about evolution.

As social animals, we are oriented toward sundry expressions of our conspecifics that ground us in the social world,1 a world of acceptance and rejection, approach and avoidance, that features objects rich with significance and meaning.2 Music inherently procures the detection of intention and emotion, as well as whether to approach or avoid.3

Social behavior is a premium cognitive adaptation, reaching greater depths in humans than in any other species. The orientation of the human child, for example, to a physical domain of objects, can appear quite similar in the performance of some tasks to the common chimpanzee or orangutan in the first few years of development.4 The understanding of objects in space, quantities, or drawing inferences is not that far apart. This is not so for problems requiring a vast array of social knowledge. What becomes quite evident early on in ontogeny is the vastness of the social world in which the human neonate is trying to gain a foothold for action.5 Music is social in nature; we inherently feel the social value of reaching others through music or by moving others in song across the broad social milieu.

In this chapter, I discuss how music fits into the evolution of our cognitive capabilities, and how the auditory system, larynx, motor systems, and cephalic expansion underlie the expression of music and the evolution of social contact.

Cognitive Capabilities and Problem Solving

Theodosius Dobzhansky is often cited for his remarks regarding how all things are linked to evolution.6 A biological perspective is the cornerstone in understanding our capabilities, with our musical ability being just one of these, including our sense of space and time, our ability to assess probabilities (the prediction of events), our numerosity, and, of course, our language abilities.

The specific adaptation for decoding facial responses, and the more general aptitudes such as applying numerical capabilities to diverse problems, pervade a biological understanding of cognitive adaptation. Cognitive systems run the gamut across the nervous system. Cognition is not simply defined by a province of the neocortical tissue, the most evolved tissue; cognitive systems are distributed across neural systems that traverse the brain stem to the forebrain.7 As I have indicated, and will continue to note throughout this book, regions of the brain that underlie musical sensibility and expression are also widely distributed.8

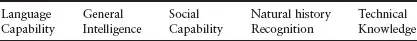

Cognition rests at the heart of human understanding. Table 1.1, originally created by the evolutionary anthropologist Steven Mithen, highlights some of the core features of problem solving and human expression.9

TABLE 1.1

Forms of Problem Solving and Human Expression

Source: Adapted from Mithen, 1996.

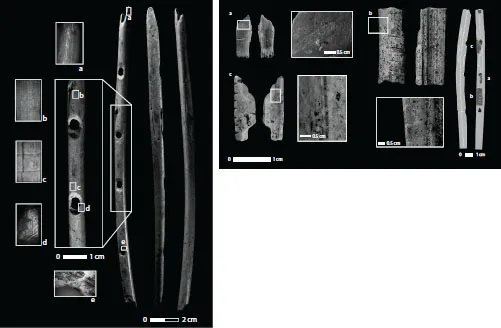

Figure 1.1 Bone and ivory flute fragments from the Hohle Fels and Vogelherd caves in southwestern Germany.

Source: Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature, Conrad Malina and Munzel, “New flutes document the earliest musical tradition in southwestern Germany,” copyright 2009.

These are fairly diverse sets of cognitive predilections that underlie our evolution and figure into much of what we do. Cave painting, tool making, and other skills, as well as our sense of enjoyment in what we do, are embedded in cognitive adaptation and a search to understand something about our surroundings: what to expect, how to cope, how to transform, and so on. After all, Art As Experience, as Dewey understood, is in understanding, building, and representing affective content.10

From simple tools to facile musical instruments, to elementary symbols, all of these represent a small leap for humankind. For example, see the flutes depicted in figure 1.1. Diverse forms of art and probably music emerged in early Homo sapiens, and are evident in remains that date back to at least 40,000 years ago.11

Knowledge and a sense of aesthetics are entwined. They coalesce as heightened appraisals predominate in functional contexts; then reprieves occur, long silences and meditative calms amidst the hustle and bustle of life. Reconsidering and musing take precedence amid ephemeral moments of reflection and meditation; artifacts take shape and expand from narrow confines to extended attraction from normal bodily expression. The body is expanded through meditation with a direction set in motion by an evolving brain.

One cognitive adaptation is the capacity for the basic discernment of inanimate objects from animate objects. We have adapted this fundamental cognitive perception into a source of music, art, and religion. We represent animate objects, often giving them divinelike status, which infuses them with specific and transcendental meaning. This is part of a basic adaptation to discern useful objects.

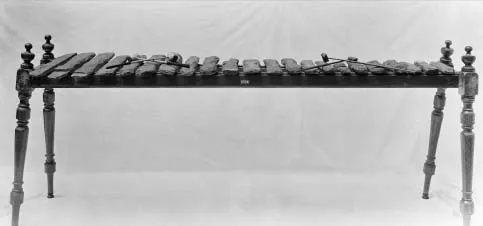

Musical instruments ultimately derive from this expanded cognitive approach to objects. A key artifact is something that is sometimes called a “sound tool” or “lithophone.” The oldest date back some 40,000 years ago from sites in Europe, Asia, and Africa.12 Sound tools are simple stones that resonate when struck, as shown figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Flint sound tool, known as a lithophone.

Source: Rock Harmonicon, by William Till. Ca. 1880. United Kingdom. Gneiss and hornblende schist, H. 106.7 × L. 247.7 cm (42 × 97 ½ in.); Longest stone: 77 cm (26 in); Shortest: 22.9 cm (9 in.). The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.2931). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, U.S.A. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resources, NY

While most of music is song, and song preceded musical instruments, the cognitive/motor cephalic capability for the invention of tools is embedded in music and meaning, with social contact inherent in these events.13 After all, making objects, musical and otherwise, is a cephalic extension of the world beyond ourselves. The terrain changes, and we scaffold with the broadening array of musical meaning.14

Representing objects, dividing kinds by naming and tracking them,15 is also fundamental to human evolution. Cognitive capacities continued to expand as we explored new terrains and survived in them. Thus, representation is not something that removes us from objects. Instead, the cognitive expansion into art and the knowing process of reflection and meditation provides ways of coming to understand the objects that matter and mean something to us.

Time and Timing

Time is not a thing. Despite the fact that we know something about the neural systems that regulate the perception and organization of time, this concept is still highly theoretical; it is a cardinal feature of our cognitive apparatus, with phylogenic roots in basic clock mechanisms.16 We have used our diverse cognitive resources to expand upon our grasp of time; we recognize simple concepts of periodicity an...