![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Arc of the Book

Why do some social platforms flourish while others die? What is a social strategy, and what distinguishes a strong social strategy from a weak one? To begin to examine these concepts in depth step back for a moment and consider the meteoric rise of online social platforms. The first set of dedicated online social platforms launched in 1995 when Classmates made its appearance, and then SixDegrees followed in 1997. Neither gained significant traction, and both closed quickly. Then, when Friendster launched in 2003, followed by MySpace and Facebook, the social revolution stormed the Internet. By the time this book was in press in late 2013, Facebook, the largest online social platform, had amassed more than 1.25 billion users, who made more than a trillion connections and uploaded more than 240 billion photos.1 Twitter—a U.S.-based social platform providing real-time communication between friends and strangers—had garnered 232 million users.2 eHarmony, one of the leading online matchmaking sites, with more than one million paying users, claimed to be responsible for almost 5 percent of all new heterosexual marriages in the United States.3 Meanwhile, in China, WeChat, a mobile text and voice communication software, with some Facebook-like functionalities, boasted more than 500 million active users.4

Initially, social platforms were considered a passing fad. But given the breadth of adoption, few now doubt that they fulfill important social needs. And upon reflection, the popularity of these platforms is not surprising. Most of us have friends. Platforms that enable us to interact with them easily therefore have understandable appeal. Moreover, at various points in our lives, most of us want to make new friends or find a partner, and before the advent of social platforms, there were few large-scale outlets for meeting these social needs. So when technology allowed social platforms to emerge and a critical mass of people became aware of the possibilities, pent-up demand quickly translated into broad adoption.

In other ways, however, the popularity of these platforms is deeply surprising. After all, before these platforms took off people used to meet new people in the offline world and maintained relationships with friends, and no one lamented the absence of an online social platform. This begs the question: Why do we need online social platforms to interact with others when we can interact in the offline world?

Social Failures

To answer this question, I argue that there are many interactions in the offline world that we would like to undertake but cannot. These missing interactions represent unmet social needs, or social failures. In some cases, these social failures relate to inability to meet new people—I will refer to these as “meet” failures. In other cases, they pertain to the in-ability to share private information or social support within the context of existing relationships—I will refer to them as “friend” failures. These failures lie at the heart of why people are attracted to social platforms, and we will review them in more detail in chapter 2.

Social Solutions

In chapter 2, we will also examine how to build social features that, when put together, create successful social solutions that allow people to meet strangers or deepen their existing friend relationships in ways they could not do on their own. As we do this, we will seek to distinguish between strong social solutions that truly address social failures from weak social solutions that do little to alleviate social failures. We will use this distinction to help us understand why some social platforms have won over others.

Subsequently, we will turn to broader strategic questions and examine competitive interactions between different types of social solutions. Such analysis can help us answer questions such as: What stops Facebook from replicating LinkedIn’s solutions and adding them to its current offering? Or, more generally: Why do we not see one all-encompassing social platform that provides social solutions to all of our social failures?

To answer such questions, I argue that there exist powerful strategic trade-offs that cause two or more social solutions to be less effective when they are provided by the same platform. To avoid these negative implications, social platforms will refrain from copying solutions provided by other types of platforms. When this happens, different types of platforms with non-overlapping solutions will coexist. As we will see in later chapters, it is exactly such trade-offs that prevent Facebook from replicating what LinkedIn is doing. They also stop one large social platform from providing all types of solutions.

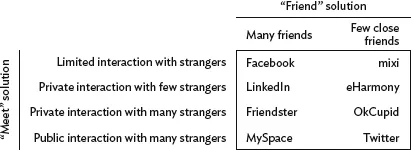

Strategic trade-offs can arise in many different ways. In this book, however, I focus on trade-offs that arise between different ways of helping us interact with people we do not know and with those we already do. Specifically, I will show that platforms that offer “meet” solutions face trade-offs between: (1) allowing private interaction with a few strangers, (2) allowing private interaction with many strangers, or (3) permitting unlimited public interaction with strangers. These are illustrated on the vertical axis of table 1.1, together with examples of platforms that exemplify these choices. Chapters 3 and 4 will discuss these trade-offs in detail using the examples of eHarmony, OkCupid, and Twitter, respectively. This discussion will help us understand why eHarmony, which offers private interaction with a limited number of strangers, would not be as effective if it also allowed private interaction with many strangers. Similarly, it will identify when platforms offering private interaction functionalities, such as a dating site, may wish to refrain from providing public interaction functionalities—something that Twitter provides.

In contrast, as shown on the horizontal axis of table 1.1, platforms that offer “friend” solutions face a trade-off between helping users to interact with a small number of their closest friends or with a large number of their friends and acquaintances. As we will see in chapter 5, where we will study Facebook and mixi, these interaction choices lead to distinctive positioning, preventing one type of platform from replicating the appeal of the other.

Table 1.1. Strategic Trade-offs among Social Platforms

Finally, we will focus on platforms that provide solutions to help people meet strangers but also facilitate interactions with friends and acquaintances. In chapter 6, we will use LinkedIn and Friendster as examples of such platforms, and show that they generate user behaviors that would be unacceptable on platforms like Facebook. This will help us explain why Facebook makes it so difficult for us to interact with strangers, which in turn allows LinkedIn to compete in a distinct manner. We will end our analysis in chapter 7 with MySpace, which provided solutions for users to interact with a broad set of friends but also allowed them to interact publicly with many strangers, leading to user behaviors that would undermine the efficacy of platforms offering other solutions.

Social Strategy

Having understood what makes social solutions work and how they compete with one another, the second half of the book focuses on how businesses that cater mainly to our economic needs, such as Ford or Procter & Gamble, can leverage social platforms for competitive advantage.

Many companies have already tried to do this by acquiring fans on Facebook or followers on Twitter, and broadcasting promotional messages to them. Despite the apparent promise, the results of such actions are often disappointing. Either companies fail to engage their customers or, when they do, they find it difficult to convert that engagement into real sales.

I attribute this relative lack of success to the fact that such broad-casting actions do not help people do what they like to do on such platforms—interact with others to solve their social failures. Instead, these commercial messages interfere with the process of making human connections. To see why, imagine sitting at a table having a wonderful time with your friends, and then suddenly someone pulls up a chair and asks, “Can I sell you something?” You would probably ignore that person or ask him to leave immediately. This is exactly what is happening to companies that try to “friend” their customers online and then broadcast messages to them.

But companies can successfully leverage social platforms for competitive advantage. To do so, they simply need to help people do what they naturally do on social platforms: engage in interactions with other people that they could not undertake in the offline world. To continue the earlier analogy, companies can walk up to that table and say, “Hi! Can we help you become better friends with the people you are with?” When companies provide a social solution that addresses unmet social needs, they can then ask people to undertake certain corporate tasks, for example, contribute free inputs, produce goods for the company to sell, or market or sell these goods on the company’s behalf. By performing these tasks, people lower the companies’ costs, or increase their ability to charge higher prices, which translates into greater competitive advantage. I will refer to the confluence of social benefits and greater competitive advantage as a successful social strategy.

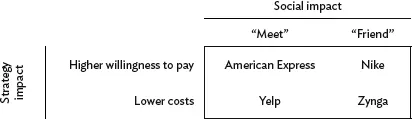

Chapter 8 introduces this concept in more detail and examines two key decisions that arise when developing a social strategy: Should such a strategy aim for higher willingness to pay or for lower costs? And should the company achieve this goal by providing a “meet” solution or a “friend” solution? I then dedicate one chapter to each of the four possible configurations of social strategy that result from answering these questions (see table 1.2).

Specifically, chapter 9 examines Zynga’s social strategy, which aims to lower costs by facilitating relationships between people who already know each other. Chapter 10 looks at Yelp’s social strategy, which seeks to reduce costs by promoting relationships between people who did not previously know each other. Chapter 11 introduces us to the social strategy that encourages a higher willingness to pay while facilitating new relationships, and shows us that established firms, such as American Express, can pursue many social strategies at the same time. Chapter 12 rounds off this analysis by reviewing some of the preceding types of strategies, and adding one, used by Nike, that increases willingness to pay while strengthening existing relationships.

Table 1.2. Types of Social Strategies

To help managers prepare to construct their own social strategies, chapter 13 focuses on the process of social strategy development at the Harvard Business Review. Chapter 14, the conclusion, summarizes the book.

Key Choices I Made about the Book’s Content

Every author makes choices when writing a book. I would like to high-light three choices I made. First, I chose to introduce a number of my own terms rather than using existing ones. For example, other than in the subtitle, I chose not to use the term social media. This is because to me the term implies content creation and broadcasting. As we will see later, such activities comprise only a small percentage of how people engage with others online. Instead, I opt to use the term social platforms, to underscore that people connect online, using whatever means, in whatever form, primarily to improve their relationships with others. I also avoid the term online social networks because that term implies interacting with one’s existing set of friends and acquaintances. People often meet new people online, however, and for this reason I prefer to use the all-encompassing term social platforms.

Second, I chose to downplay the histories of various social platforms and the personalities of the executives who ran (and run) them. I cover those details in the Harvard Business School cases I have written on these companies. Instead, in this book, I concentrate on examining various social platforms against a common framework. Doing so allows me to highlight, compare, and contrast their similarities and differences with ease. (By the time you finish the first part of the book, you will see more similarities than differences between eHarmony, Twitter, and Facebook.)

Finally, in writing the book, I explicitly excluded all social platforms hailing from China. When the book was written, Chinese users could not access many of the Western social platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube. This allowed a multitude of Chinese social platforms to emerge and meet the social needs of Chinese Internet users. Documenting this complex ecosystem requires a separate book—one that I hope to write soon!

The Book’s Audience

This book is primarily aimed at scholars interested in understanding why we use social platforms, how these platforms compete with each other, and how more traditional firms can leverage social platforms for competitive advantage. I hope that the ideas presented here will inform both sociology and strategy, and encourage their further integration. Specifically, I hope that my colleagues in sociology will benefit from understanding the kinds of social platforms that are likely to emerge in the future. And I trust that my colleagues in strategy will be convinced that puzzling over the details of social behavior can have a tremendous impact on how firms compete in the marketplace.

Separately, I hope that this book will help practicing managers. I suspect that most managers will be drawn to the second part of the book, where they can find examples of what c...