![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Liberation of Islamic Letters

BINT AL-SHATIʾ’S LITERARY LICENSE

Bint al-Shatiʾ’s writings crystallize some of the most salient themes of the modern Islamic public sphere and illustrate the power of adab in formulating modern Islamic ethics and politics. A public intellectual, political activist, chaired professor, journalist, and adība (woman of letters), Bint al-Shatiʾ (the penname of ʿAʾisha ʿAbd al-Rahman) synthesized discursive trends for a broad spectrum of readers that included both intellectual elites and popular audiences. Enjoying an illustrious career as an Islamic intellectual, she drew on the authority of revivalist discourses and traditional religious disciplines like tarājim (religious biography), tafsīr (Qurʾanic exegesis), and the sciences of the Arabic language. Yet she was neither of al-Azhar (although she was the first woman invited to lecture there) nor of the Muslim Brotherhood but of Cairo University and ʿAin Shams. From these more secularly oriented institutions, she mainstreamed ideas of the Islamic intellectual sphere—in the press, lectures, and popular publications. She helped reconfigure adab, literature, for the adab—the ethics, morals, and values—of the emergent Islamic awakening. Perhaps most important, she articulated the gendered dimensions of this Islamic public sphere, writing about women in the Prophet’s family, women’s emancipation in Islam, women’s rights, women in Islamic law, and women writers. Her writings contributed to making the world of letters, religion, and women the very axis for articulating an Islamic body politic.

Bint al-Shatiʾ (1913–1998) circulated in the most eminent intellectual circles of her time, among figures whose lives and careers were defined by the intersection of religion and literature. Like her, they used literary techniques to reinterpret classical religious sources; like her, they brought new kinds of training to traditional scholarship. She expanded the intellectual legacy of intellectual foremothers like Labiba Ahmad and Fatima Rashid, even as she clearly emulated her male colleagues—her husband Amin al-Khuli, her dissertation adviser Taha Husayn, her colleague ʿAli ʿAbd al-Wahid Wafi, her sparring partner ʿAbbas Mahmud al-ʿAqqad, and his protégé Sayyid Qutb. Although clearly influenced by and refracting intellectual currents of these circles, she was no mere “copy” of these thinkers, as the novelist and playwright Tawfiq al-Hakim accused her of being.1 On the contrary, she was able to synthesize intellectual arguments for popular audiences, meld literary creativity and religious scholarship, build on theories of the liberating nature of Islam, and put the intimate domain in the front center of Islamic cultural production. The Islamic world of letters articulated middle-class values as Islamic ones through gendered interpretations of intimate relations in the private sphere.

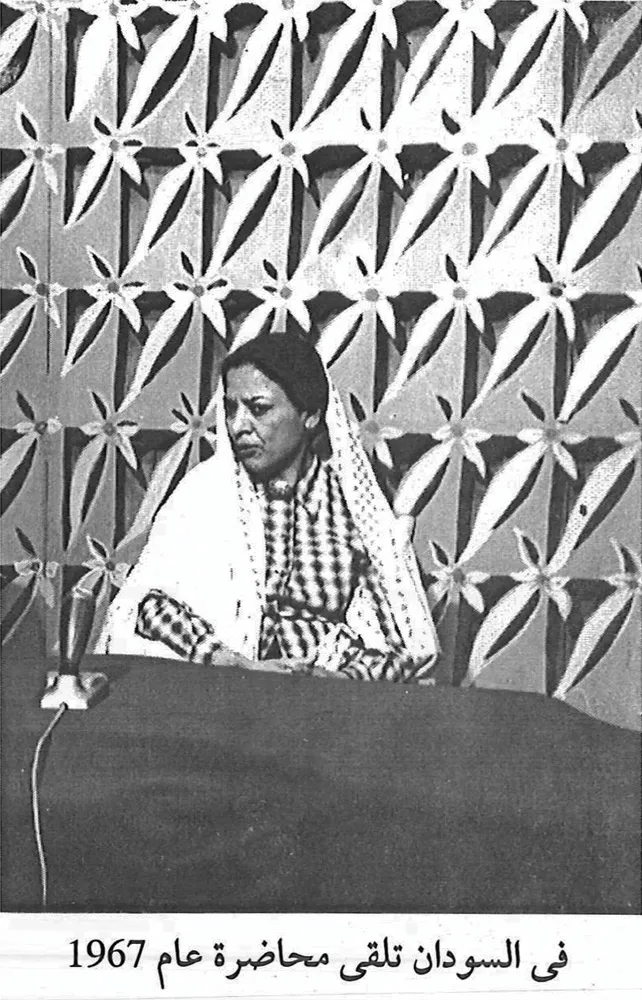

Bint al-Shatiʾ lecturing at the Islamic University of Omdurman in 1967. Image courtesy of Hasan Jabr.

Epitomizing a new kind of Islamic intellectual not formally educated in religious institutions or disciplines, Bint al-Shatiʾ became a popular authority on the Qurʾan and religious literature. The spread of public education and literacy created literate audiences for these writings, opening up religious knowledge and religious texts to portions of the populace for whom they had previously been inaccessible. By deploying new approaches and techniques, she reconfigured religious knowledge for the modern middle class. One of the most important parts of the spread of education was the increased literacy of women, and Bint al-Shatiʾ was one of the first fruits of this generation. Even as she firmly situated herself as an Islamic scholar, she was not trained in Islamic institutions but at Cairo University. She did not (officially) specialize in Islamic studies but earned her degree in Arabic literature. She used alternate channels (Arabic literature and poetry, the press, literary writings, popular literature) to access domains of Islamic learning largely closed to women of her age. In doing so, she helped throw its doors open to women’s religious scholarship and to the women’s Qurʾanic exegesis that followed. One of the ways she did this was by rewriting classical Islamic stories into new, popular literary forms. Her biographies of women in the Prophet’s family read like romance novels, even though they are carefully grounded in rigorous religious scholarship. Through new modes of popular writings, she helped disseminate formal religious learning among a newly emergent reading public.

A lion(ess) of the literary establishment, Bint al-Shatiʾ enjoyed an intellectual trajectory that spanned eras and genres. Through her own publishing career, she connected the surge in Islamic literature of the 1930s and 1940s to the awakening of the later 1970s and 1980s. Literary writing played a key role in catalyzing the rise of an Islamic public sphere, connecting the awakening (nahḍa) of the late nineteenth century to the later awakening known as the ṣaḥwa. Precisely because of her position at the center of public institutions, she was able to visibly sustain a newly decentralized Islamic discursive tradition throughout the secularly oriented Nasser era. Her writings provided a public outlet for religious discourse at a time when the Muslim Brotherhood was driven underground, the religious courts were abolished, and al-Azhar was put under the control of the state. Her literary production during the Nasser years laid the foundation for the intellectual Islam of the later revival, especially the gendered politics that became so critical to the literature of the ṣaḥwa.

Bint al-Shatiʾ drew on classical models of adab, the Qurʾan, sunna, tafsīr, literature, and poetry, yet she also formulated a contemporary vision of the “Islamic personality,” one rooted in political lexicons of freedom and responsibilities, rights and duties.2 She used new kinds of Islamic humanities to envision new kinds of Islamic selves. Her primary frame of reference is al-bayān, the Qurʾan. Throughout her career, the concept of al-bayān is a constant and multivalent point of reference. The word, language, speech, eloquence, the very articulation that God gave to humanity (al-bayān) becomes the path to human enlightenment, the means of emancipation from ignorance, the way of awakening the self through knowledge. In a pivotal lecture that she presented at the Islamic University of Omdurman, “al-Mafhum al-Islami li-Tahrir al-Marʾa” (The Islamic Understanding of Women’s Liberation, 1967), she quotes a verse from the Qurʾan referring to al-bayān no fewer than three times: to open the lecture, to drive her point home in the lecture’s climax, and to close the lecture. “The merciful. Taught the Qurʾan. Created humanity. Taught it eloquence (al-bayān)” (55:1–4).3 These verses could be said to encapsulate Bint al-Shatiʾ’s Islamic humanism, realized through the practice of eloquent speech, through God’s word, and through His signs. Bint al-Shatiʾ uses this Islamic humanism to articulate a political project of women’s rights in Islam—to knowledge, to education, to participation in the world of letters, to public scholarship, to free speech, to debate and deliberation about Islam’s “established principles.” The human, she says, becomes complete only through the power of intelligence and articulation (al-bayān: also, “the Qurʾan”), distinguishing the human from the “mute beast.” This human right to knowledge is “our intrinsic and authentic right to life, this is not extrinsic to us, nor is it a foreign import. It is the book of Islam in us” (6).

The Adab of Islamic Humanities

Bint al-Shatiʾ came of age during a time of literary flourishing, when secular intellectuals were tackling religious themes. They used modern narrative techniques—journalism, short stories, novels, theater, contemporary biography, family romance—to reinterpret classical sources for popular audiences. In Egyptian public life, especially between the late 1920s and late 1940s, literary writing helped develop a modernist hermeneutics for Islamic thought.4 Literary treatments of religious texts dominated the world of letters during this time, as the most illustrious innovators of Arab literature in the twentieth century treated scriptural subjects through modern genres.5 This approach developed largely from intellectuals who had come from secular backgrounds, written on secular topics, and emulated Western models of knowledge earlier in their careers.

Discourses of revival (iḥyāʾ, nahḍa, baʿth) were integral to Islamic publishing during this time, with the aim of “awakening” classical literature, generating new kinds of literary production, and building the new on the basis of the old. Historians proffer a number of explanations for the shift toward religious themes in the 1930s and 1940s, among them the “revival of the Islamic-Arab cultural legacy as the basis of modern society and culture” and “the desire to appeal to new literate publics . . . through the use of popular forms and themes of literary production.”6 Integral to this process was the formulation of a “non-Western national ideology based on indigenous values which could be accepted as a modern framework of identity by broad sectors of society.”7 These writers drew on a spiritualist paradigm that sought to counter the dehumanizing effects of colonial modernity with a newly enchanted humanistic approach (what these thinkers call a “revival of the spirit”). This new literary movement infused religious “aura” into supposedly secular forms of technological reproducibility, belying Lukács’s formulation that modern narrative forms like the novel depict “a world . . . abandoned by God.”8 This new kind of literature reinterpreted traditional religious sources for the modern age, imagining a religious community in terms accessible to a broad, contemporary reading public. New genres and narrative styles did not so much break with the Islamic intellectual tradition as reconfigure it in new forms of communicability. Theorists like Benedict Anderson and Walter Benjamin interpret modern mass media as secular and as destroying sacred and traditional modes of art. But more recent scholarship by thinkers like Charles Hirschkind and Brian Larkin analyzes the power of new technologies to communicate religious sensibilities and create “anew the grounds for communal belonging.”9 The affective site of the family has been a particularly powerful vehicle for communicating—and reproducing—religious sensibilities, a realm of intimate relations continually defined and redefined in public discourses.

A new genre of religious writing known as islāmiyyāt emerged during this period, deploying artistic license to paint idealized portraits of the early Islamic community (the aslāf). Using a modernist humanism to reinterpret religious texts, this literature emphasized the Prophet’s humanity and the “divine inspiration” that produced the miracle of the Qurʾan. There were several principal genres of islāmiyyāt, the main ones being travelogues of the pilgrimage, biographies of the Prophet, biographies of the aslāf, and eventually, literary interpretations of the Qurʾan. One of the first exemplars of this kind of literature was Muhammad Husayn Haykal’s biography of the Prophet, Hayat Muhammad (Life of Muhammad, 1935), which drew on classical sources but was narrated as a modern biography—a response to and reformulation of orientalist portraits of the Prophet. An earlier proponent of (the secularly inflected) Pharaonism and an author of Egypt’s “first” novel, Haykal emphasized that the miracle of the Qurʾan was a “human” and “rational” one, even as he drew on romantic notions of the Prophet as divinely inspired. Through this approach, writers like Haykal employed a modernist humanism toward reinterpreting the divine miracle of the Qurʾan. Haykal characterized his biography as “striving for freedom of thought. However strange it may sound, this is the message of Muhammad and the foundation of his preaching.”10 The humanistic freedom of Islam would become both the central theme of Bint al-Shatiʾ’s later religious writings and a foundational concept of writings connected to the ṣaḥwa.

Bint al-Shatiʾ would almost methodically master the different genres of islāmiyyāt, using it as a path to guide her own popular cultural production. She first wrote about her experience of the ʿumra (the lesser pilgrimage), then composed extensive tarājim (biographies) of women from the Prophet’s family, and finally ventured her own literary exegeses of the Qurʾan. Through vivid portraits of the early Islamic community, Bint al-Shatiʾ and other leading intellectuals of her time employed a kind of literary Salafism to imagine an idealized umma, principally through biographies of the aslāf. Curiously, Bint al-Shatiʾ would start writing other works on Islam only after the death of her husband, the Islamic scholar Amin al-Khuli. In her autobiographical work ʿAla al-Jisr (On the Bridge, 1967), published just after al-Khuli’s death, Bint al-Shatiʾ describes how she wanted to pursue Islamic studies at the university. Al-Khuli encouraged her to instead study Arabic language and literature—perhaps because of her gender—arguing that she had to first master this primary tool for understanding religion.11 Master this tool she did, completing her dissertation on the eleventh-century poet Abu al-ʿAlaʾ al-Maʿarri. Her dissertation was supervised by the great literary scholar Taha Husayn, another intellectual who experimented with literary approaches to religious texts. He, too, had written his dissertation on al-Maʿarri at the newly opened Cairo University (then called Fuʾad University), after leaving his religious studies at al-Azhar.12 From the beginning of her scholarly career, Bint al-Shatiʾ had fought for the right to go to school, first against her own father’s opposition. She garnered support from her mother and maternal grandfather, an Azhari shaykh, whom she often credits when invoking her own intellectual lineage. Her intellect was fiercely precocious. Even before beginning the university in 1934, she acted as editor-in-chief for Labiba Ahmad’s Islamically inflected journal for women, al-Nahda al-Nisaʾiyya (Women’s Awakening).13 No sooner had Bint al-Shatiʾ entered Cairo University than she became al-Khuli’s spiritual and intellectual companion—and his second wife. While still in college, she published two well-received books ...