![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHAT WAS LIFE?

Answers from Three Limit Biologies

“What was life? No one knew.”

—Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, 1924

WHAT IS LIFE? A GATHERING consensus in anthropology, science studies, philosophy of biology, and even the biological sciences themselves suggests that the theoretical object of biology, “life,” is today in transformation, if not dissolution. Proliferating technologies of assisted reproduction, along with genomic reshufflings of biomatter in such practices as cloning, have unwound the “facts of life.”1 Biotechnology, biodiversity, bioprospecting, biosecurity, biotransfer, and other things bio- draw novel lines of property and protection around organisms and their elements (e.g., genes, organs), which now circulate in new ways as gifts, as commodities, and as tokens of social belonging or exclusion.2 From cultural theorists and historians of science we learn that “life itself,” consolidated as the object of the discipline of biology around 1800, has morphed, as material components of living things—cells and genes—rearrange and disperse, and exist in distributed laboratory choreographies that have them frozen, amplified, and exchanged.3 Writers in philosophy, rhetoric, and cultural studies of science, meanwhile, claim that as “life” has become the target of digital simulation and bioinformatic representation, it has become virtual, mediated, and multiple.4

All these transformations unsteady any naturalistic or ultimate foundation that life forms—embodied bits of vitality like organisms and species—might provide for forms of life—social, symbolic, and pragmatic ways of thinking and acting that organize human communities.5 In the language of anthropology, these changes unsettle the nature so often imagined to ground culture. Life moves out of the domain of the given into the contingent, appearing not as a thing-in-itself, but as something-in-the-making in discourse and in practice. “Life” becomes a term increasingly placed within scare quotes—even in the pages of the most cited scientific journal in the world, Nature, which (as I report in the introductory chapter to this book) in 2007 published “Meanings of ‘Life,’” an editorial calling for the abandonment of “life” as a scientific term of art. “Life” becomes a trace of the scientific and cultural practices that have asked after it, a shadow of the biological and social theories meant to capture it.

In his 1802 discipline-dubbing book, Biologie, the German naturalist Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus asked, “What is life?” a question that, as it has traveled into the present, has admitted of various answers.6 The physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s 1944 What Is Life? offered that life might issue from a hereditary “code-script,” which conception became in subsequent years enlisted into models of DNA and into informatic and cybernetic visions of vitality.7 Fifty-one years after Schrödinger, the microbiologist Lynn Margulis and the writer Dorion Sagan offered a less unitary account in their book What Is Life?, in which they delivered a distinct answer to the question for each of life’s five kingdoms: bacteria, protists, animals, fungi, and plants—emphasizing neither some underlying logic nor an overarching metaphysics but rather the situated particulars of microbial, fungal, plant, and animal embodiment; life was not something that could be compressed into the linear logic of a code but instead was a process ever overcoming itself in an assortment of embodied manifestations.8 If Schrödinger’s model fit into forms of life calibrated to Cold War practices of coding, secrecy, and cryptography, Margulis and Sagan’s view speaks to a world in which environmentalism and biodiversity—and their unknown futures—organize many contemporary forms of hope and worry.

But if it is now possible to think of life as having a variety of plural futures—as a 2007 conference, “Futures of Life,” held in the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University had it—it is also possible, in the face of a seemingly endless multiplication of forms, to inquire, as did a 2007 conference at Berkeley, What’s left of life?9 That question, posed by scholars in the humanities and social sciences, asked whether what Michel Foucault in 1966 identified as life itself, the epistemic object of biology that Foucault claimed first manifested in the early nineteenth century, still retains its force to organize matters of fact and concern—life forms and forms of life—arrayed around the life sciences.10 It is a limit question, a worry about ends. What was life?

How has it become possible for scholars in the sciences and humanities to declare the possible end of “life”? How has the following diagnosis, offered by rhetorician Richard Doyle, become possible?

“Life,” as a scientific object, has been stealthed, rendered indiscernible by our installed systems of representation. No longer the attribute of a sovereign in battle with its evolutionary problem set, the organism its sign of ongoing but always temporary victory, life now resounds not so much within sturdy boundaries as between them.11

If, as Foucault argued, biopolitics brought “life and its mechanisms into the realm of explicit calculations”—that is, if it drew on life science knowledge to organize practices of governance (public health programs, reproductive policies, etc.)—what happens to such politics as life delaminates, escapes itself?12

Where is life off to?

What was life?

This essay offers possible answers to those questions, drawing on anthropological fieldwork I conducted among biologists in the late 1990s and in the first decade of the 2000s. In that ethnographic work, I pursued the question of what “life” is becoming for those professional biologists who worry very explicitly about the limits of life, both as an empirical matter of finding edge cases of vitality and as a matter of framing an encompassing theory of the biological, a theory that might unify all possible cases. In the three scientific communities I studied, such limit accounts of life forms are tethered—sometimes explicitly, more often implicitly—to claims about the forms of cultural life proper to a world in which understandings of nature and biology are in revision. Life forms and forms of life inform, transform, and deform one another.

THREE LIMIT BIOLOGIES

In the 1990s, scientists working in the field of Artificial Life dedicated themselves to modeling evolutionary and biological systems in computers. Many claimed not just to be simulating life in silico, but also to be synthesizing new life in cyberspace and in robots. For practitioners, “life” could be decoupled from its carbon instantiations and might one day supersede organic life. In Silicon Second Nature, I analyzed how scientists working in Artificial Life, in dialogue with post- and transhumanists, argued that digital life forms would reveal the informatic logic of evolution, ushering in a science-fiction world in which “life” would become fully technological, a pattern transposable across media.13

Around the turn of the millennium, a parallel community of biologists sought the limits of life in another context—not cyberspace, but ocean space. In Alien Ocean, I looked to marine biologists studying microbes in extreme ecologies, like deep-sea hydrothermal vents.14 These scientists’ encounters with organisms thriving at extremes of temperature, chemistry, and pressure pressed them against the boundaries of assumptions about organic embodiment—with implications for comprehending the limits of life on Earth and for thinking about how political ecological forms of life (e.g., the consumption of fossil fuels) might encounter or, perhaps, overcome biological limits. With work with microbes that engage in lateral gene transfer—mixing up genes “within” generations, that is, with their contemporaries—even taxonomy, the naming of life forms, became unstable, with implications for apprehending the possible natural and technical malleability of living things.

Moving from ocean space to outer space, another group of limit biologists—astrobiologists—have been keen to theorize and scout out life at its boundaries. My research among astrobiologists investigated how these scientists define and discern “biosignatures,” possible signs of extraterrestrial life present either in extraterrestrial rocks that have made their way to Earth or in the remotely read atmospheric profiles of other worlds.15 Astrobiologists seek traces of possible life elsewhere in the solar system or galaxy and hope that such findings can be read back to situate Earthly life in a cosmic ecology.

I here read across these three ethnographic examples to suggest that biological studies in which “life” is conceptually stretched to a limit resonate with uncertainties about what kinds of sociocultural forms of life biology might now anchor. Limit biologies such as Artificial Life, extreme marine microbiology, and astrobiology can be read as symptomatic of the emergence elsewhere, in less ivory-towerish zones of practice, of growing instabilities in concepts of nature—organic, earthly, cosmic.16 Such instabilities can be fruitfully mapped by attending to how scientists of extreme biologies test the limits of form in life forms.17 If, as Treviranus wrote in Biologie, “the objects of our research will be the different forms and manifestations of life,” those forms are being deformed by the object and form of biological inquiry.18 While there are implications here for the stability of the “bio” in biopolitics, I am equally interested in how biologists think about limits—and I think that the very notion of the limit, as an object of study and fascination in biology and in interpretative social science, also requires analytic scrutiny. At the essay’s close, I train attention on limits in order to understand some limits of “theory” today, as it is transforming within both professional biological discourse and critical inquiry.

ARTIFICIAL LIFE: LIFE FORMS AT THE LIMITS OF ABSTRACTION

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the rise of Artificial Life, a hybrid of computer science, theoretical biology, and digital gaming devoted to mimicking the logic of biology in the virtual worlds of computer simulation and in the hardware realm of robotics. Named by analogy to artificial intelligence, Artificial Life promised to deliver a fully formalized account of life, one that could be instantiated across a variety of platforms, including, most crucially for practitioners, computational media.19 My 1990s fieldwork among Artificial Life scientists was centered at New Mexico’s Santa Fe Institute for the Sciences of Complexity, where researchers claimed that life would be “a property of the organization of matter, rather than a property of matter itself.”20 Some found this claim so persuasive that they held that life forms could exist in the digital medium of cyberspace; they hoped that the creation of such life could expand biology’s purview to include not just life-as-we-know-it, but also life-as-it-could-be—life as it might exist in other materials or elsewhere in the universe. On the initiate’s view, Artificial Life’s extreme abstraction leverages biology into the realm of universal science, like physics, with a formalism applicable anywhere in the cosmos.

The founder, Chris Langton, characterized the ethos behind Artificial Life as animated by “the attempt to abstract the logical form of life in different material forms.”21 This definition of life holds that formal and material properties can be partitioned and that what matters is form. What was form for Artificial Life scientists? Two things: information and performance.

INFORMATION

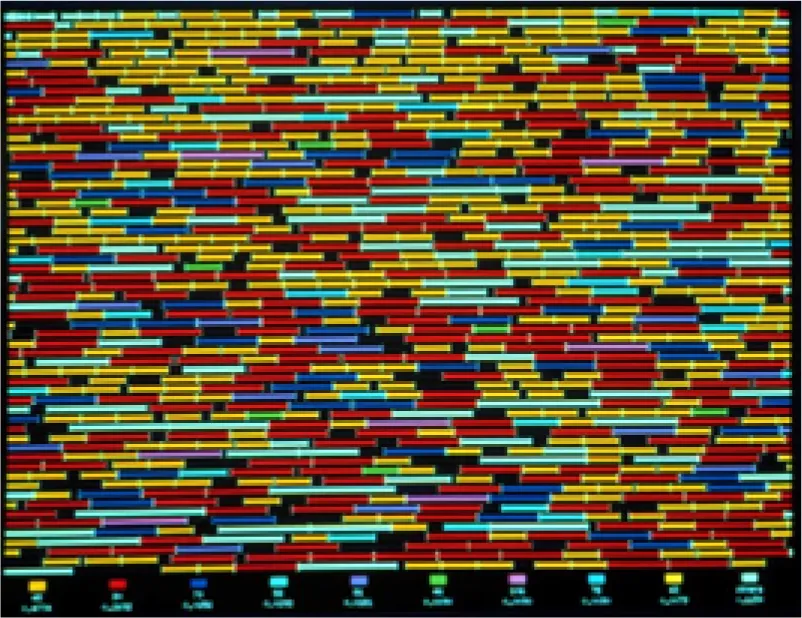

Artificial Life founded its reputation on computational models of evolutionary dynamics. One of the most popular models during my fieldwork was the biologist Tom Ray’s “Tierra,” a system in which assembly language programs resident in random-access memory (RAM) self-replicate based on how efficiently they make use of central processing unit (CPU) time and memory space. Ray described these programs as “digital organisms” and characterized Tierra as a “universe,” writ in “the chemistry of bits and bytes,” within which only the fittest survive (see figure 1.1). For Ray, who was trained as a tropical ecologist and self-taught as a programmer, Tierra was not so much a model of evolution as it was “an instantiation of evolution by natural selection in the computational medium.” “Digital life,” Ray wrote, “exists in a logical, not material, informational universe.”22 Ray understood life to be a process of information replication and, like many of his Artificial Life colleagues, interpreted genetic code as analogous to computer code; in fact, the analogy was so tight that he considered it an identity. “The ‘body’ of a digital organism,” he urged, “is the information pattern in memory that constitutes its machine language program.”23

Figure 1.1. A screenshot of Tom Ray’s Tierra, visualizing space taken up by “digital organisms” within random-a...