![]()

ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL,

PROPHET OF DIVINE PATHOS

If I say, I will not mention him,

or speak any more in his name,

there is in my heart as it were a burning fire

shut up in my bones,

and I am weary with holding it in,

and I cannot.

—Jeremiah 20:9

IT IS FITTING TO BEGIN THIS BOOK with a chapter on Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, whose description of the prophet as one who shares the divine pathos for humanity characterized not only his own life but also those of each of the seven figures who follow. Born on January 11, 1907, in Warsaw, Poland, Heschel, named after his grandfather, was the youngest of six children; he had four sisters and one brother. His mother, Reizel (Perlow) Heschel, and father, Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Heschel, were each descended from distinguished Hasidic rebbes, a family of nobility in the Jewish world. “Yes,” he remarked in later years to an interviewer, “I can trace my family back to the late fifteenth century. They were all rabbis. For seven generations, all my ancestors have been Hasidic rabbis.”1 At the age of eight or nine, he began to study the Talmud, the massive collection of rabbinical commentaries and debates. According to his daughter, Susannah, “As a small child he was accorded the princely honors given the families of Hasidic rebbes: adults would rise when he entered the room, even when he was little…. He would be lifted onto a table to deliver … learned discussions of Hebrew texts. He was considered … a genius.”2 His ancestral pedigree did not shelter him, however, from the anti-Semitism of his Polish environment. As he recalled in a 1967 interview with a Benedictine priest, “I have been stoned and beaten up many times in Warsaw by young boys who had just come out of church.”3 When his father died at the age of forty-three during a flu epidemic, Heschel was nine years old. His uncle, Rabbi Alter Israel Shimon Perlow, took over the responsibility of supervising his education.

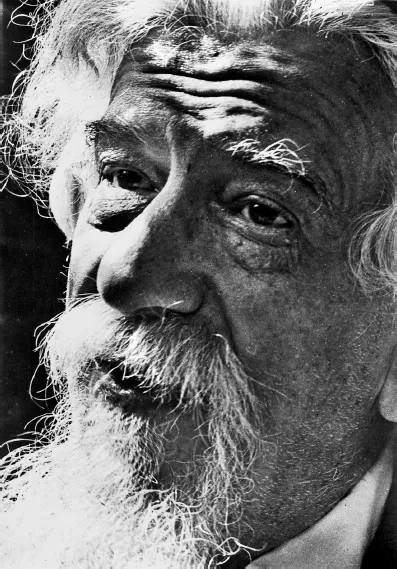

Figure 1.1 Abraham Joshua Heschel. Courtesy: CSU Archives / Everett Collection.

Hasidic and Kabbalistic spirituality had a profoundly formative as well as lasting influence on the young Heschel’s religious experience and worldview. He absorbed the teaching of the Ba’al Shem Tov, the revered founder of Hasidism, that “we are called to see the holy sparks within all created beings … and to bring together the sparks to preserve single moments of radiance and keep them alive in our lives, to defy absurdity and despair and to wait for God to say again: Let there be light. And there will be light.”4

In later years, Heschel fondly described his childhood heritage:

I was born in Warsaw, Poland, but my cradle stood in Mezbizh (a small town in Ukraine), where the Ba’al Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name), founder of the Hasidic movement, lived during the last twenty years of his life. That is where my father came from, and he continued to regard it as his home…. I was named after my grandfather, Reb Abraham Joshua Heschel—“The Apter Rav,” and last great rebbe of Mezbizh. He was marvelous in all his ways, and it was as if the Ba’al Shem Tov had come to life in him…. Enchanted by a wealth of traditions and tales, I felt truly at home in Mezbizh. That little town so distant from Warsaw and yet so near was the place to which my childish imagination went on many journeys.5

The adult Heschel would express his lifelong devotion to Hasidism in aphorisms such as “I have one talent and that is the capacity to be tremendously surprised, surprised by life…. This is to me the supreme Hasidic imperative,” and “The claim that we not only need God but that God needs us is likewise nurtured from Hasidic roots.” As Heschel says in his book about Hasidism, The Earth Is the Lord’s: “The meaning of man’s life lies in his perfecting the universe. He has to distinguish, gather, and redeem the sparks of holiness scattered throughout the darkness of the world. This service is the motive of all precepts and good deeds. Man holds the key that can unlock the chains fettering the Redeemer.’”6 By the time he was a teenager, Heschel was writing his first articles, short studies in Hebrew, of Talmudic literature, which were published in a Warsaw rabbinical journal, Sha’arey Torah (Gates of Torah) in 1922 and 1923. Deciding he wanted exposure to secular knowledge and culture, he left home for high school in Vilna, Lithuania, at the age of seventeen. Vilna was at the time the center of Eastern European Jewish life and culture, a magnet for poets, philosophers, and religious seekers. There he helped organize a club of young Jewish writers and artists called Young Vilna, and composed his first poems. Although he no longer dressed like a Hasid or studied exclusively religious texts, Heschel continued to observe Jewish law and remained proud of his heritage.

Having passed his final high school exams in June 1927, he decided to study in Berlin and enrolled at the age of twenty at the Academy of Scientific Jewish Scholarship, which trained Liberal rabbis and scholars, and at the University of Berlin. In April 1929, Heschel passed the required entrance exams in German language and literature, Latin, mathematics, German history, and geography. He chose philosophy as his major field, with minors in art history and Semitic philology. Down the street from the academy was the Hildesheimer Seminar, the Orthodox rabbinical seminary. Heschel was one of the few students able to move easily between the two institutions. In a private seminar taught by the social philosopher David Koigen, Heschel developed a vision of a traditional Judaism responsive to the contemporary world. In the decade he spent in Berlin (just as Adolf Hitler came to power), he refined philosophical and theological categories with which to explain religious thinking, prophetic inspiration, and Hasidic piety.7

In December 1929, he passed the examinations at the academy in Hebrew language, Bible and Talmud, Midrash, liturgy, philosophy of religion, and Jewish history and literature, and in May 1930, he received a prize for a paper he wrote, “Visions in the Bible.” He was also appointed as an instructor, lecturing on Talmudic exegesis to the more advanced students. In July 1934, he passed his oral examinations and was granted a rabbinical degree after completing a thesis titled “Aprocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, and Halakah.” On February 23, 1933, just three weeks after Hitler seized control of the government, Heschel took oral examinations for his doctorate at the University of Berlin and passed. That same year his first book, a volume of Yiddish poems, The Ineffable Name of God: Man, dedicated to his father’s memory, was published in Warsaw. Several of his poems foreshadowed major themes in his later theological work and the aphoristic poetic style in which he wrote. For example, “God’s Tears” heralds his belief that sharing in the divine pathos for human suffering reverses the usual criteria of social and moral judgment:

God’s tears lie on the cheeks

of shamed, weak people

Let me wipe away His lament

He in whose veins there whirls

a quiet shudder before God,

let him kiss the nails of a pauper

To the worm crushed under-foot

God calls out “My holy martyr!”

The sins of the poor are more beautiful than

the good deeds of the rich.

In “God Follows Me Everywhere,” he celebrates God’s allusive presence intimated by our capacity for wonder and “radical amazement”:

God follows me everywhere—

Spins a net of glances around me,

Shines upon my sightless back like a sun.

God follows me like a forest everywhere.

My lips, always amazed, are truly numb, dumb,

Like a child who blunders upon an ancient holy place.

God follows me like a shiver everywhere.

My desire is for rest; the demand within me is: Rise up,

See how prophetic visions are scattered in the streets.

I go with my reveries as with a secret

In a long corridor through the world—

and sometimes I glimpse high above me, the faceless face of God.

God follows me in tramways, in cafes.

Oh, it is only with the backs of the pupils of one’s eyes that one can see

how secrets ripen, how visions come to be.8

In December 1932, Heschel had submitted his dissertation, “Prophetic Consciousness,” which was approved by his committee. For reception of the doctoral degree, however, the university required that the dissertation be published. Heschel did not have the money to pay for publication and had to appeal to the dean for repeated delays until finally, in 1936, the Polish Academy of Sciences published it, with the costs borne by the Erich Reiss Publishing House in Berlin. In 1937, at the age of thirty, Heschel left Berlin for Frankfurt to replace Martin Buber as director of a Jewish adult school since Buber was immigrating to Palestine to escape the inexorably expanding Nazi persecution. In 1938, Gestapo agents awakened Heschel in the middle of the night. They gave him two hours to gather his possessions and report to the local police station as required by a new law ordering the deportation to Poland of all Jewish residents of Germany holding Polish passports. Loaded down with two heavy suitcases of books and manuscripts, Heschel boarded a train so overcrowded that he was forced to stand for most of the three-day journey. At the Polish border, the refugees were confined in a squalid detention center. Heschel’s family eventually managed to arrange for his release. But it was all too clear that the situation for Jews in Poland was increasingly precarious.

In spring 1939, he received an invitation from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati from its president, Julian Morgenstern, to join the faculty—part of Morgenstern’s initiative to save Jewish intellectuals from the Nazis. To escape meant that Heschel had to leave his family, for whom visas were not available. That summer, he left for England six weeks before the Nazis invaded Poland. He stayed with his older brother, Jacob, who had left Warsaw one year earlier, until he was finally able to obtain a visa in March 1940 for the United States. On arrival in New York, he stayed in Brooklyn with his oldest sister, Sarah, the only one of his sisters to escape Europe.

In fall 1940, Heschel began teaching at Hebrew Union College. Five difficult years ensued. He was not yet fluent in English, and his observance of Jewish dietary and ritual obligations set him apart from the customs of the Reformed institution. He took meals in his room since the cafeteria didn’t keep kosher. He also found the American students much less prepared to handle Hebrew texts than those he had taught in Germany. Efforts to save his mother and three sisters in Poland failed, and they perished in the Holocaust. Years later in his inaugural lecture as a visiting professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York, he would epitomize the tragedy by introducing himself “as a person who was able to leave Warsaw, the city in which I was born, just six weeks before the disaster began. My destination was New York; it would have been Auschwitz or Treblinka. I am a brand plucked from the fire in which my people was burned to death. I am a brand plucked from the fire of an altar of Satan on which millions of human lives were exterminated to evil’s greater glory.”9

In 1945, Heschel met a young concert pianist, Sylvia Strauss, at a dinner party. They discovered that they shared mutual interests in music, philosophy, and art, and fell in love. In December 1946, they married and moved to New York City, where Heschel accepted a teaching position as a professor of Jewish mysticism and ethics at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the center of Conservative Judaism in the United States. Their only child, Susannah, was born in 1952.

From his small, overcrowded office at the Jewish Theological Seminary, a steady stream of books began to appear, including essays on the philosophy of religion from the perspective of the phenomenological analysis of religious experience; biographies of Jewish thinkers such as Moses Maimonides and Abravanel; the circle of followers of the Ba’al Shem Tov; an elegiac depiction of the Eastern European Hasidic culture destroyed by the Shoah; and theological reflections on the Sabbath, the relationship of human beings and God, and a masterful revision in English translation of his dissertation on the consciousness of the prophets. As Susannah Heschel noted, “One looks hard to find discussion of [direct] political activism in my father’s scholarly and theological writing of the 1940s and ’50s. As he later explained in an interview, it was revising his dissertation on the prophets for publication in English during the early 1960s that convinced him that he must be involved in human affairs, in human suffering.”10

In The Prophets, Heschel offered his clearest articulation of the connection between religion and politics, sanctity and social activism. The relationship between God and human beings is not only that of creator to creature but also one of mutual partnership. He made this radical claim: “God is in need of human beings.” We all see the cruelty of humans and the misery they cause, but strive to stifle our conscience by cultivating indifference. Note that Heschel does not exempt himself from blame but speaks of “we,” including himself among the ranks of those Thomas Merton would call “guilty bystanders.” As Heschel would famously put it, “Few are guilty but all are responsible.” It is the divinely imposed task of the prophet to break down the wall of our indifference by voicing the suffering and anguish of the poor, the widow, the orphan, and the oppressed of our society.11

To the prophet … God does not reveal himself in an abstract absoluteness, but in a personal and intimate relation to the world. He does not simply command and expect obedience; He is also moved and affected by what happens in the world, and reacts accordingly. Events and human actions arouse in Him joy or sorrow, pleasure or wrath. He is not conceived as judging the world in detachment. He reacts in an intimate and subjective manner, and thus determines the value of events. Quite obviously in the biblical view, man’s deeds may move Him, affect Him, grieve Him or, on the other hand, gladden and please Him. This notion that God can be intimately affected, that He possesses not merely intelligence and will, but also pathos, basically defines the prophetic consciousness of God.

Unlike the unmoved mover of the philosophers,

unknown and indifferent to man … the God of Israel is a God Who loves, a God Who is known to, and concerned with, man. He not only rules the world in the majesty of His might and wisdom, but reacts intimately to the events of history. He does not judge men’s deeds impassively and with aloofness; His judgment is imbued with the attitude of One to W...