![]()

PART I

An Overview of Brazil in Transition: Beliefs, Leadership, and Institutional Change

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

SINCE 1994, BRAZIL HAS BEEN ON A RELATIVELY VIRTUOUS PATH OF economic and political development, though there have been bumps in the road. Is twenty years long enough to conclude that Brazil is still on the road to a sustainable developmental path whose hallmarks are social inclusion with steady economic and political development? Or, were the past twenty years simply a flash in the pan similar to the short-lived Brazilian miracle of the late 1960s and early 1970s? This time, the miracle is for real because of a change in beliefs in Brazilian society and consequent changes in economic and political institutions. Today, the dominant belief held among those in power as well as the majority of the population is in “fiscally sound social inclusion.” How did this belief emerge? And, moreover, what are the forces that will sustain it? To understand the changes in Brazil over the past fifty years, we wed the concepts of windows of opportunity, beliefs, dominant network, leadership, institutions, and economic and political outcomes into a framework to understand the dynamics of institutional change and the beliefs within which they are nested.1 Development is contextual; that is, each country must find its own way. Brazil is no exception, though the concepts developed in this book have purchase in understanding institutional development or persistence elsewhere.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND CRITICAL TRANSITIONS

Our main theme is the process of development in the modern world. The purpose is to better understand the forces leading some contemporary societies to achieve economic and political development while most societies remain in autopilot. “Development” may seem fairly intuitive; yet, all countries manage to grow during some periods and almost all develop to some extent over time. However, few countries manage to complete what we call the “critical transition,” which is a more fundamental change in a country’s circumstance than simply increases in GDP.

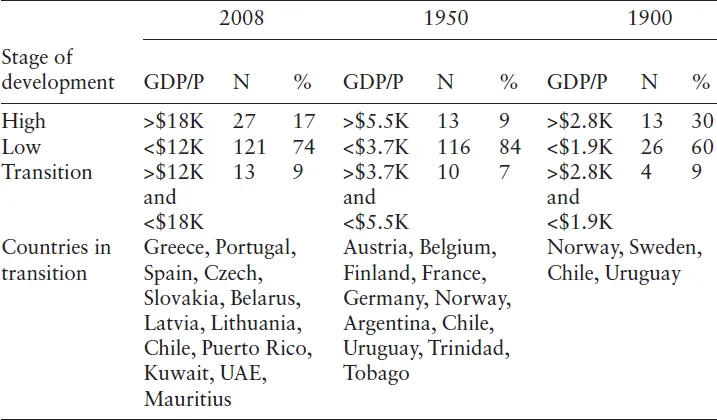

To see that the process of development entails a transition from one state to another, rather than simply an incremental change along a continuum, note that it is common for analysts—whether growth theorists, development economists, political scientists, journalists, or others—to classify countries into two broad groups. There are rich and poor countries; developed and developing; center and periphery; First World and Third World (the Second World disappeared with the fall of communism); industrialized and nonindustrialized; and open-access and limited-access orders. Although the labels and the associated theoretical approaches differ, the basic notion is that there are two categories. It is natural then for the interest to center on trying to understand the determinants of the transition from one group to the other. It turns out that recent cases of countries making the transition are quite rare. It is not simply a matter of time until most countries grow themselves from the bottom to the top category. In table 1.1, we used the Maddison Project data set to classify each of the countries for which there was GDP per capita data, as being in the high income, low income, and middle/transition categories.2 We did this for three different years spanning the data set—1900, 1950, and 2008. In order to classify the countries, the choice of cutoff for the high group was chosen somewhat arbitrarily to include countries that are normally accepted as being “developed” at that time, and the cutoff for the low group was set at two-thirds (66.7 percent) of that level. Given the propensity to classify all countries into just two groups, the countries between the low and the high groups are considered as being in transition from one to the other. As expected, there are fewer countries in the high GDP per capita group than the low group (note that in 1900, the limited data availability biases upward the proportion of those in the high group). Strikingly, the number of countries in the transition group is always relatively small—less than 10 percent. The last row in the table names the countries in the transition group, which allows one to see that this group would be even smaller if we reassigned the special cases (Puerto Rico, Kuwait, UAE in 2008, and war-torn Europe in 1950). Furthermore, some of the transition countries are transitioning downward (such as Argentina and Uruguay in 1950), corroborating the notion that countries making the transition from the bottom to the top group is a relatively rare occurrence. Although the numbers in table 1.1 depend on the criteria used to classify the countries (see note to table), the general conclusion that there is a small high-income group and a large low-income group, with few transitioning countries in between, is quite robust. This flies in the face of the notion that poor countries will inexorably grow over time and catch up with richer countries, known as the convergence hypothesis, which has been a major debate in economics in the past decades.3

TABLE 1.1. Number and Percentage of Countries: High, Low, and Transition

Source: Calculated using data from the Maddison Project (Bolt and van Zanden 2013).

Note: Data: GDP per capita in 1990 Int. GK$. Countries classified by the following criteria: 2008—High (GDP/P > $18,000), Low (GDP/P < $12,000), Transition ($12,000<GDP/P<$18,000); 1950—High (GDP/P > $5,500), Low (GDP/P < $3,666), Transition ($3,666<GDP/P<$5,500); 1900—High (GDP/P > $2,800), Low (GDP/P < $1,866), Transition ($1,866<GDP/P<$2,800). Upper bound is 1.5 times the lower bound.

The evidence in table 1.1 refers solely to GDP per capita. Although higher levels of income and wealth are necessary for a critical transition, this concept requires important changes in several other dimensions as well. Many times, an increase in GDP per capita can take place in circumstances that are not sustainable or that compromise future growth, creating a middle-income trap. A critical transition, in contrast, requires not only economic improvements but also accompanying changes in social relations (e.g., greater equality) and political institutions (e.g., alterations of power and checks and balances). Therefore, a country that has achieved a critical transition has done something significantly harder and more fundamental than simply raising its GDP. Note that according to the classification in table 1.1, Argentina was a high-income country in 1900 (GDP per capita $2,875), in transition in 1950 ($4,987), and in the low-income group in 2008 ($9,715), suggesting that although incomes were high at the outset, other conditions were lacking. In the opposite direction, although Austria, Belgium, France, and Germany are classified as in the transition group in 1950, this was a temporary setback due to the two world wars, suggesting that the other fundamental conditions besides GDP that had promoted the development of these countries in the nineteenth century were still in place.

The conditions besides GDP growth that are necessary for a critical transition vary from country to country. By examining those countries that have achieved sustainable development, we can see that there are many common features, such as rule of law for all, political openness and universal participation, free entry and exit for all sorts of organizations (business, political, religious, and associational), checks and balances, electoral uncertainty ex ante, and certainty ex post. No country has all these features, and each has its own set of quirks and dysfunctionalities, but by and large their institutions share a related set of such characteristics and generally lack other conflicting elements, such as authoritarianism, inequality, segregation, favoritism, and systemic violence.

Brazil is currently poised to make the critical transition. Given that only a handful of countries have managed to do this in the past decades, it is incumbent on us to back up this claim with evidence and argumentation. Furthermore, given that Brazil’s performance in terms of GDP growth has been merely mediocre in past decades, we need to make a strong case that other fundamental changes are taking place that are setting the stage for economic growth to follow. In chapter 2, we present a basic framework for understanding how countries develop or fail to do so. In chapters 3–6, we provide a detailed analysis of the changes in Brazil since the 1960s. We show that the country has become economically orthodox, politically open, and socially inclusive, with all these three areas marked by a general respect for the rules. The characteristics, which are now firmly rooted and less likely to be reverted by eventual shocks, have never been aligned in such a way in Brazilian history and contrast markedly with the state of the country just a few decades ago. Previously, chronic fiscal and monetary indiscipline kept the country in a perpetual inflationary state with high internal and external indebtedness. Misguided and excessive state intervention fostered inefficiencies, distorted markets, reduced productivity, and left market failures unaddressed. Politics was at different times mired in different combinations of authoritarianism, corruption, clientelism, populism, nepotism, electoral fraud, gridlock, and exclusion. Socially, the country was highly unequal—among classes, races, regions, and sectors—with lack of opportunity for the disadvantaged and few effective policies seeking to address these imbalances through redistribution. Though some of these problems persist, there have been huge strides.

BRAZIL: THIS TIME FOR REAL?

Brazil currently boasts the world’s sixth largest economy, and it has been undergoing a profound transformation toward its critical transition. At first blush, this is a bold claim because the rates of GDP growth during the past twenty years, especially at the start of its transition, have been generally unremarkable and often disappointing. But, as noted earlier, a critical transition is about more than GDP growth; it also includes economic opportunity and distribution as well as genuine political competition and democratic stability. On these scores, we demonstrate in the empirical section that Brazil is a different country now than it was twenty years ago.

We are bullish about the changes in Brazil, but the perception by much of the media inside and outside of Brazil is that the slowdown in economic growth is an indication that once again the glory years are lost. This replacement of hope and confidence with skepticism and despondency is not hard to understand. From 1975 to 1994, the country underwent two decades of unrelenting economic decline during which a crippling process of hyperinflation wreaked havoc with individuals’, organizations’, and governments’ attempts to structure their lives and to plan for the future. To many, the repeated frustrations and failures of this period destroyed the country’s self-esteem and instilled a sense that perhaps this dysfunctional state of affairs was not a phase to be overcome, but rather a natural Brazilian characteristic.

Since 1994, things have changed for the better. Inflation has been kept under control, and several economic indicators have clearly improved, some of them remarkably so. Poverty and inequality have been falling for more than ten years; the country’s debt ranks as investment grade; agriculture and other exports are booming; international reserves are above US$350 billion; extensive oil reserves have been discovered; and powerful politicians involved in corruption scandals have faced tremendous reputational costs, and some have been tried and punished by the Supreme Court. Over this period, Brazil has consolidated a vibrant, competitive, and liberal democracy in a global context in which generalized elections have often not resulted in guarantees and safeguards to citizens’ civil and individual rights.

And yet, there remains a nagging feeling among analysts and the Brazilian public that these achievements may merely be a temporary good spell of the sort the country has often had in the past, but which inevitably ends in tears. Perhaps the most salient argument along these lines is that all these achievements are a direct consequence of the world’s commodity boom since 2003 and now that this has ended, everything will come crashing down.

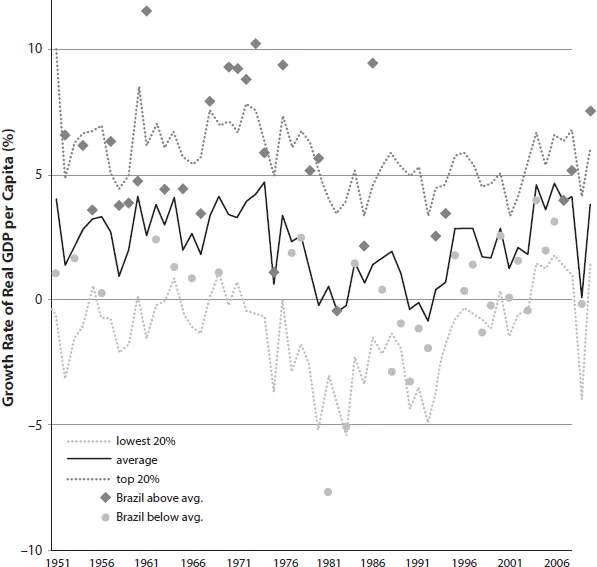

Skepticism about Brazil’s achievements as well as its future prospects is not gratuitous. An examination of several indicators of performance and prosperity provides sufficient ground to be suspicious of claims that the country has deeply changed. Figure 1.1 shows Brazilian GDP per capita growth rates from 1950 to 2010. For the purpose of comparison, the figure also shows the average GDP per capita among all countries as well as the boundary for the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent countries in each year. The figure differentiates when GDP per capita in Brazil grew above and below the average. The data show that prior to 1980, Brazil performed overwhelmingly above the world average and often above the top 20 percent mark. Since then, however, its performance has been, more often than not, below average. This is not an obvious candidate for a study of a country on a successful transition to sustainable development.

Other indicators are equally ominous. In the United Nations’ Human Development Index, Brazil was only 85th out of 187 countries in 2011. In the World Bank’s 2011 Doing Business ranking, which compares the ease of doing business across countries, Brazil was ranked 126th out of 183. The Legatum Prosperity Index puts Brazil at 42nd out of 110 in 2011. In the Heritage Foundation’s 2012 Index of Economic Freedom, Brazil was in the “mostly unfree” category, ranking 99th out of 179 countries. In terms of corruption, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) places Brazil at 69 out of 174 countries in 2012. In 2012, Reporters without Borders ranked Brazil at 99 out of 179 countries in terms of the freedom of press. In the 2009 OECD PISA test for educational attainment for fifteen-year-olds, Brazil came in 50th, 55th, and 51st out of 62 countries in reading, math, and science, respectively.4 These are clearly not the kind of rankings that would make a country stand out as an example of successful development. In most categories cited above, Brazil seems woefully distant from the leading group. How is it then that we justify our choice of Brazil as a country on the road to prosperity?

Figure 1.1. Brazilian GDP per capita growth relative to the rest of the world. Sources: Heston, Summers, and Aten (2009) data for 1950–2007 in constant 2005 prices; IMF for 2008–2010 data, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/02/weodata/download.aspx.

Rather than trying to discredit these indexes and the comparisons they purport to allow, we find that such attempts at measuring different dimensions of a country’s performance can often be quite useful. It is naive, however, to expect a successfully developing country to simultaneously and monotonically improve all or even most of these dimensions throughout that process. The process of development is inherently messy and contextual, and no combination of indicators ever provides a sure telltale sign of whether a definitive transition is really underway. Many of the indicators measure performance variables that vary widely over time, reflecting cyclical rather than deeper determinants. Other indicators are built using perceptions by experts, businessmen, and other individuals, for example, the CPI (Transparency International) and the Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank). Yet, perceptions are often overly influenced by more salient current information and are often subject to herd behavior. Tetlock (2006) has shown the weakness of expert opinion at predicting issues such as which countries will thrive and which will fall. His twenty-year study with a large and varied sample of experts from various fields concluded that even those who by definition should be knowledgeable predict only marginally better than chance.

Furthermore, there are several indicators in which Brazil fares remarkably well, for example, 10th out of 133 in “soundness of banks” in 2009; 15th out of 236 in number of documents published in scientific journals from 1996 to 2010; and first in a ranking of developing countries’ efforts to fight hunger.5 Another shortcoming of using any arbitrary assortment of indexes and indicators to infer the true nature of a country’s process of development is t...