![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE SECULAR PILGRIM

OR, THE HERE WITHOUT THE HEREAFTER

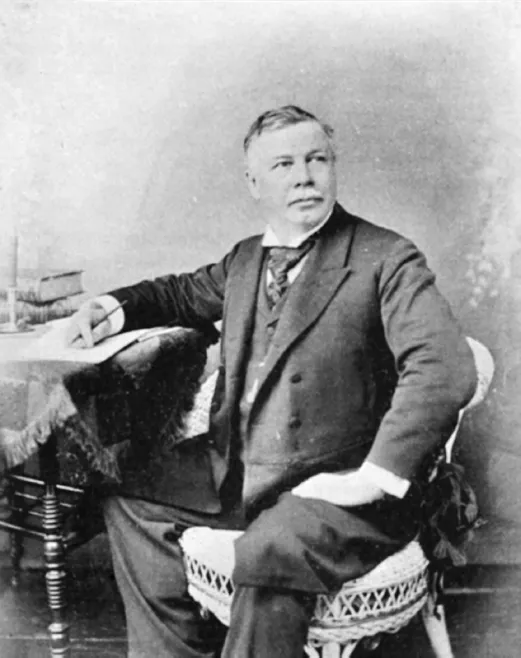

SAMUEL PORTER PUTNAM WAS “BRED IN BLOOD AND BONE” in the orthodoxy of New England’s old Congregational order. His father, Rufus Austin Putnam, was a Harvard graduate, class of 1822, who spent his entire career in the parish ministry. The wandering son recollected his steady father—he “never yielded one iota of his orthodox convictions”—with almost formulaic images of severity. Rufus had been as austere and unloving as the Father God he extolled: “He seemed a kind of grand shadow in my childhood. I do not remember that there was ever a flash of real sympathy between us.” The scattered farmers of Chichester, New Hampshire, would gather each Sabbath to hear the patriarch preach his undiluted Calvinism: “All were fellow-travelers to eternity, and heaven was the goal,” Samuel recalled. “Only a few, however, expected to get there, and the terrors of hell-fire were expatiated upon with fear and trembling.” Decades afterward, Putnam expressed only bitterness toward the long Sabbath services of his childhood and the haunting fright of his father’s sermons: “Many a night I awoke crying with terror,” scared that his prayers for a “new heart” would come to naught and that he was among the damned. To a small boy, in that tiny church under his father’s care, Protestant orthodoxy had felt inescapable and overpowering. If there were any village atheists in this New Hampshire crossroads, the pastor’s son never met them: “To be an Infidel at that time, in that place, was an almost unheard-of monstrosity.”1

FIGURE 1. Samuel Porter Putnam, from Samuel P. Putnam, 400 Years of Freethought (New York: Truth Seeker Co., 1894), plate at p. 518. Author’s Collection

In penning My Religious Experience (1891), Putnam imagined his life story as a Puritan counternarrative, a testimonial antitype. To be able to give a credible account of regeneration was at the heart of his evangelical Calvinist upbringing; he had heard about the marks of genuine conversion “all the years of my childhood.” But, when it came time to relate his own experience, he selfconsciously plotted a reverse pilgrimage from the one his father had projected for him. Among the few books besides the Bible that the young Putnam remembered being explicitly encouraged to read was John Bunyan’s classic allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). Bunyan’s Christian—a model Puritan saint—anxiously traverses a treacherous, narrow, temptation-laden path to get to the Celestial City. Among the distractions Christian encounters is Atheist who, scoffing at the dreary journey the pilgrim has undertaken, has stopped looking for Mount Zion and is heading back to the City of Destruction. Bunyan’s saint, of course, remains true to his faith and quickly moves past Atheist, whose only remaining god is this world. In narrating his religious experience, Putnam effectively rewrote that archetypal Protestant narrative from Atheist’s viewpoint. No longer a sojourner making his way in the light of eternity, Putnam became an itinerant freethinker, “a confirmed Materialist and Atheist,” and a paradigmatic American secularist. His was an earthbound pilgrimage, not a celestial one. Putnam’s self-chosen sobriquet—“the Secular Pilgrim”—made that Puritan antithesis unmistakable.2

Putnam saw his “passing from the heart of orthodoxy to Freethought” as a liberating progression, but that hardly made it a straightforward process. It was, as Putnam acknowledged, “a varied journey,” not a linear march from religious authority to secular enlightenment, but an unsteady dance with his Protestant inheritance. In hindsight, the end point of his countervailing pilgrimage into atheism may have looked foregone, but it unfolded in multiple stages—with at least two switchbacks into the faith and three separate stints in Congregational and Unitarian ministries. For a long time, Putnam was not sure whether he wanted to extricate himself from Christianity entirely or instead to reimagine it on liberal Protestant terms; even his split from evangelical Calvinism never looked so much like a neat divorce as a family psychodrama. Having haltingly removed himself from the pulpit’s long shadow, he would try out a series of public reinventions: as a customs official, a novelist, a traveling lecturer, an editor, and a historian. Around one self-transformation, however, he built an elaborate secret—his momentary boldness as a free lover. All narratives are unfaithful, but Putnam’s relation of his religious experience proved doubly so. He studiously hid the sexual implications of his infidelity as well as the vulnerabilities of his secular identity behind a facade of atheistic assurance and finality.3

To say that Putnam’s secular pilgrimage was paradigmatic warrants some specification. The snaking route by which he relinquished his evangelical Calvinism for atheistic materialism involved all the major conduits of secularism’s formal articulation: (1) liberalizing religious movements that pushed within and then beyond Protestantism—Unitarianism and the Free Religious Association were key institutionalized expressions; (2) organized forms of freethinking activism—the National Liberal League and American Secular Union stood out; and (3) expanding media platforms to spread the secularist message—coast-to-coast lecture circuits and successful weekly journals, including the Index and the Truth Seeker, were critical. Putnam was a wayfarer through all of these religious fluctuations and irreligious developments. “When … I think of the seminary, and orthodox pulpit, and Liberal ministry, and the Secular pilgrimages, and the immense theological and metaphysical spaces I have traversed,” Putnam remarked on a roving lecture tour in 1886, “I feel about a million years of age. It has been a round-about journey, during which God, heaven, and hell have disappeared like so many sparks, and only the earth remains.” That could have been the epitaph for the secular pilgrimage Putnam embodied and exemplified: only the earth remained. The empyrean horizon of the hereafter dimmed to vanishing in the fleshy immediacy of the here-and-now. And yet Putnam’s journey also disclosed the very fragility of that disappearance—how much work was required to keep the celestial from reinserting itself into his own allegory of secularism’s triumph.4

Putnam recalled his mother, Frances, more fondly than he did his father. She was “more companionable,” more “open to the sunlight and beauty of this world.” The big meals Frances prepared for Sunday evenings marked the reentry of some bodily delight after a full day at the meetinghouse; apart from a little whittling on the sly between the morning and afternoon sermons, Putnam considered his mother’s Sabbath fare the day’s only consolation. Not that she was anything less than a faithful churchgoer, the proper helpmeet for her husband’s ministry, but Samuel saw in her a greater ease with earthly enjoyments, tender emotions, and mundane responsibilities. The son recalled Monday washdays, for example, as glittering and happy by comparison to Sabbath observances; his mother presided over the duties in which “things seemed real” and his father over the errands that seemed impalpable. Putnam here traded on a series of familiar gender oppositions in which his father was cerebral and remote and his mother corporeal and sociable, but his observations were nonetheless suggestive. His mother was “a good cook,” and, late in life, Putnam was ready to set down those Sunday meals as his first taste of a secular pilgrimage—a gustatory indication, within his strict Sabbatarian upbringing, of how freeing it would be to have religious obligations give way to fleshly appetites.5

Putnam’s debt to his father also remained substantial, far more so than the son cared to admit. All the jeremiads about diminished clerical authority notwithstanding, the Congregational ministry remained an esteemed learned profession in antebellum New England. Rufus Putnam’s vocation depended on serious study and substantial intellectual training, and he had a library fit to undergird his calling’s scholarly, literary, and apologetic demands. As a youth, Samuel delved into his father’s books for hours on end. A miscellany of theology, literature, and history, the collection belied Putnam’s flat depiction of his father’s blinkered dogmatism. Among the books the son found, for example, were histories of ancient Greece that left him agape at the glories of Athens (as opposed to Jerusalem). He discovered as well the works of William Ellery Channing, the champion of New England’s liberal Christian vanguard, the herald of both Unitarianism and the wider Transcendentalist ferment of Ralph Waldo Emerson and company. The father was by no means one of Channing’s acolytes, but, as a learned minister, he had to be well versed in the theological debates that were then agitating the Congregational churches in order to shore up his own evangelical Calvinism. The son, by contrast, took Channing’s sermons as a breath of fresh air; they filled him “with a strange feeling of relief.” In the “top loft of the big old parsonage,” the son read against the grain of his father’s orthodoxy and bubbled with a youthful enthusiasm for more. Once he had his hands on Shakespeare, for example, the Bible seemed so “vastly inferior … in wealth of thought and life.” His father’s library, Putnam reminisced decades later, “was the nearest to heaven I ever got in my childhood.”6

By his mid-to-late teens, when Putnam was at Pembroke Academy prepping for his 1858 matriculation at Dartmouth College, his reading had turned decisively to Romantic poetry. He became fixated, above all, on Percy Bysshe Shelley, a poet notorious for his heterodoxy (Shelley had been expelled from Oxford for authoring a pamphlet entitled The Necessity of Atheism): “I was saturated with his genius,” Putnam effused. He described Shelley as “my Bible and my religion”; he claimed to have experienced a “new birth” through Shelley’s “brilliant revival of the Pagan and Greek spirit.” It was, of course, the opposite of the conversion for which his parents had long been praying—anti-Christian, pantheistic, if not atheistic, in its vivid rebellion. Once at Dartmouth, Putnam relished his Promethean revolt all the more and saw his irreligion as part of a heady adventure. The lingering “orthodox influences” at the college—chapel prayers and professorial admonitions—left him entirely untouched; he was blithe about the Bible’s irrelevance to his new life. Dreamy and impulsive, with Shelley as his guiding spirit, Putnam was sure that “the bands of the Puritan faith were broken” and that he would “never be anything else but an Atheist.”7

Thirty-some years later Putnam would look back with embarrassment on his “unreal and fantastic college life” and the “sentimental Infidelity” that had seized him: “My unbelief was the romance of sentiment.” He felt, in hindsight, as if he had been a Transcendentalist caricature, gasping at sunsets and starry nights and listening to the melodies of forests and fields. “They who are Infidels as I was at college, merely through the emotions, are not always able to stand the onslaught of the churches,” he admitted, “for anything built upon emotion is apt to be swept away by emotion.” He had not been schooled in Enlightenment infidelity—in Hume, Voltaire, or Paine—but instead had “come out of Christianity” much as Ralph Waldo Emerson had, on a counter-Enlightenment “wave of feeling.” The problem, as Putnam ultimately came to see it, was that his romantic pantheism still valued religious feeling and soulful epiphany, and, in that, it was “too much like sentimental Christianity.” It had taken the fifty-something infidel a very long time to see his collegiate mistake for what it was—that “religious feeling, as feeling, is wrong”—but the seriousness of that intervening intellectual struggle made him no less forgiving of his youthful naïveté. “The last superstition of the human mind,” the mature Putnam somberly averred, “is the superstition that religion in itself is a good thing.” The retention of transcendental aspiration, in whatever guise, was what ultimately needed to be dissolved.8

The grizzled atheist of 1890 had it in for the callow infidel of 1860 because of what happened next. The Civil War broke out in 1861, and the idyll Putnam had been living was swiftly blown apart. Leaving Dartmouth his junior year without graduating, he enlisted as a private in the Union Army. His father had been a staunch reformer—active in temperance, missionary, and anti-slavery societies—and the son, even in his religious estrangement, knew intimately the strenuous demands of the New England conscience. Samuel went off to war with exalted purpose and high enthusiasm—to fight for “absolute principle,” to put an end to slavery, to save the nation. He served first in the Fourth New York Heavy Artillery before being promoted in early 1864 to captain in the Twentieth U.S. Colored Infantry, a post he held until the end of the war. Camp life and the battlefield, especially “marching and counter-marching for days and weeks” in the Shenandoah Valley, came close to destroying him. “It is well enough to talk about inward strength and self-reliance,” he observed, but those shibboleths made no sense of the absolute dependency upon the circumstances of army life that he now felt. The war’s “prison-house” of dull routine and horrific violence left Putnam with one strangely Christian verity intact: “We cannot live upon what we are in ourselves.”9

On one forced march toward Washington, Putnam was overtaken by fever, hunger, thirst, and blinding pain. Suddenly, he found his “whole life’s history” flashing through his mind “with astonishing distinctness,” as if in that moment he were drowning. And that is when it happened—when the “sentimental Infidelity” of his college days proved no bar against the vast onrushing of devout emotion:

Home came before me with its sweet scenes, and mingled with the pictures the teachings I had received from father and mother; the milder aspect of religion, not the wrath of God or the fires of hell, but the love of Jesus…. With overwhelming power sounded the appeal I had so often heard: “Surrender to Jesus.” I was looking at the cross shining against an ineffable halo. There was no fear in my emotions. It was simply attraction…. Suddenly out of my weakness, my suffering, the pain, the weariness, and the despair, my heart cried out, “I surrender!” There was no reserve.

Even thirty years later, when he was once again an atheist, Putnam remained in awe of this visionary episode, his battlefield surrender to Jesus. In a twinkling he had been saved; he had been transformed: “That one can pass in a moment from darkness to light, from the deepest misery to the brightest joy, by a belief in Jesus, has been a fact in my own life.” What to make of that fact—what interpretation to give this experience—absorbed him for the remainder of his days. That he ultimately settled on “natural causes” to explain this epiphany did not make the transformation any “less real.” The fruits of the experience were, in this case, as tangible as a Monday washday.10

Putnam’s surrender to Jesus reconciled him to his childhood faith and dramatically reoriented his life aspirations. After he left the Union Army in June 1865, he decided to follow in the vocational footsteps of his father, and he headed off to Chicago Theological Seminary to train for the Congregational ministry. He went as an evangelical Calvinist much in the mold, he said, of “the theology of my parents.” While his new birth had given his faith an emotional imperative, those warmhearted feelings were necessarily filtered through all the catechesis of his upbringing. Doctrine very much shaped experience—as was evident when Putnam reflected on the theological underpinnings of his own conversion: “So far as the phenomenon of the ‘new birth’ was concerned,” he concluded, “the theologians were right. It came about just as they said it would.” Putnam went to seminary having made the standards of evangelical Calvinist piety and learning very much his own. He led with the heart perhaps, but he talked up as well the intellectual delights of the profession—the “leisure and position” it would afford him to “learn all there is to learn.” The other professions, he insisted, required too much specialized knowledge; the minister’s calling was a summons instead to “universal inquiry” into “all philosophy, all poetry, all art, all history.” His freethinking companions of the 1880s and 1890s might wonder why “any man of intelligence” would choose to enter the Christian ministry, but Putnam would never issue an apology for “the ideal ministry” he had imagined for himself in the wake of his wartime experience.11

That the reality would fall well short of the ideal was surely a given. Putnam found theological study corrosive to his religious affections; the seminary’s “intellectual gymnastics” seemed to him anything but universal. They were, rather, trivial, the equivalent of counting angels on pinheads or distinguishing “betwixt twe...