![]()

PART I

Making Meaning

Although an individual who had unusual experiences played a central role in launching each of the spiritual paths, they and their collaborators interpreted their experiences in very different ways and conceived of their paths in very different terms. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) understands itself as a religion founded by a prophet who received revelation and translated new scriptures, while AA and ACIM emphatically declare that they are not religions and that their founders were not saints or prophets or gurus. Yet both AA and ACIM are avowedly “spiritual” movements. AA conceives itself as a “way of life” and a fellowship comprised of small groups that center on the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. According to Step Twelve, the steps culminate in a “spiritual awakening” and, according to Tradition Twelve, “anonymity is the spiritual foundation of all our traditions, ever reminding us to place principles before personalities.” ACIM is “a complete self-study spiritual thought system that teaches that the way to universal love and peace—or remembering God—is by undoing guilt through forgiving others, healing our relationships and making them holy” (http://www.acim.org/AboutACIM/).

Organizationally, they are also quite different—Mormonism is a church structured by means of doctrine and covenants, AA is a democratic fellowship of small groups centered on the Twelve Steps and structured organizationally by the Twelve Traditions and Twelve Concepts, and ACIM is a networked movement of students that is resourced by several foundations and makes use of study groups, conferences, workshops, and websites, but has no formal organization apart from the two foundations tasked with publishing, distributing, and teaching the Course. Mormonism, which claims to be the true path to a religious goal, does not allow dual membership in another religion. AA, which claims to be—and has been widely recognized as—a spiritual path that is compatible with any religious goal or none at all, encourages dual memberships. Students of the Course differ regarding the extent to which the Course can be combined with other systems of thought, but given its lack of organization, they have no way to adjudicate the issue officially.

The development of each type of path presented distinctive challenges. For Mormonism, the challenge was to convince others that the golden plates were real and that Smith was the seer, revelator, and prophet of the restored church. With AA, the challenge was to convince alcoholics that it offered a transformative path and religious groups that the new path was not a (heretical) competitor. With ACIM, the challenge was to convey the radical nature of its vision and, in light of that, to clarify its relation to other paths. Despite these distinctive challenges, each group developed a guidance procedure that they believed gave a suprahuman source input into the process, through ongoing revelation to Smith (and subsequent prophets) in Mormonism, a Higher Power operating through the conscience of the group in the case of AA, and inner guidance from the Holy Spirit in the case of ACIM. This guidance procedure, once in place, provided a means of overcoming these challenges and ensuring that the emergent process stayed on its “prescribed” course.

Toward the end of the emergence process, each group coalesced around an overall understanding of what had happened, which they captured in more or less official narratives of their group’s emergence. These quasi-official origin accounts not only defined what it meant to be a member of the group, but also constituted the group as a social formation. In the Mormon case, Joseph Smith’s 1839 history was canonized as scripture along with the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants (D&C), and a few other inspired writings. AA’s official understanding of its history is represented in brief in the prefaces to the Big Book and more expansively in the histories published by AA World Services (Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age [AACOA; 1957], Dr. Bob and the Good Oldtimers [Dr. Bob; 1980], and Pass It On [PIO; 1984]). Helen Schucman’s preface to A Course in Miracles (Schucman [1977] and Schucman [1992]) provides a brief history of how it came to be; it was supplemented in the late seventies and early eighties by interviews from the collaborators that expanded on the preface. Robert Skutch’s Journey Without Distance (JWD [1984a]) provides the earliest attempt at a comprehensive insider account, and Kenneth Wapnick’s Absence from Felicity (AFF [1991]) provides a history of Schucman and the Course from the point of view of a close collaborator.

Because each group framed these events and appropriated their framed version to constitute themselves as a formation—a church, a fellowship, or a spiritual thought system—the challenge in Part 1 is to reconstruct the process as it unfolded, beginning with the sources that are as close to real time as possible. The nature of the sources is discussed in detail in the introduction to each of the case studies. Because the nature of the sources differs in each case, the chapters devoted to each case study unfold in different ways.

In Part 1, I often break with historical convention and refer to individuals by their first rather than their last names. I do so in the chapters on AA in order to comply with the requirements of the Stepping Stones Foundation Archives (SSFA) and General Service Office Archives (GSOA), which ask historians to maintain the anonymity of AA members by identifying them by their first name and last initial only. I often refer to individuals by their first names in the chapters on Mormonism and ACIM in part to keep naming conventions more uniform in Part 1, but also because it reflects the more intimate nature of microhistory, where first names are routinely used in the primary sources and are necessary at times in order to distinguish family members. In the introduction and in Part 2, in which I express my own views and focus on the main characters in the case studies, I generally refer to them by their last names.

![]()

CASE STUDY

A Restored Church

When Mormons today tell the story of their church’s origins, they usually begin where Joseph Smith began in his 1839 version of his history, which is excerpted and canonized in Mormon scripture, that is, with an account of what Mormons now refer to as his “first vision” (JSP, H1:204–46; EMD 1:59–72). The 1839 account situates his first vision in 1820 in Manchester Township in Upstate New York, near the village of Palmyra, in the context of revivals of religion. Once convicted of their sins by revival preachers, converts were expected to select and join one of the many Protestant denominations. In the story, the young Joseph Smith, at about the age of fifteen, sought forgiveness for his sins but was confused by the multitude of denominations and retired to the woods to ask God which one he should join. In response, according to this account, the Heavenly Father and his Son, Jesus, appeared in a pillar of light and, standing above him in the air, told him that he should join none of the churches, because they were all wrong. He recounted that when he told a Methodist preacher about his vision, the preacher dismissed it with great contempt and that others persecuted him because he claimed to have seen this vision.

The next major event occurred in September 1823 at his home in Manchester, when, while calling upon God, a light lit up his room and a glorious personage dressed in white appeared at his bedside. The personage said he was a messenger sent by God to tell him of a book “written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent and … [containing] the fullness of the everlasting Gospel … as delivered by the Saviour to the ancient inhabitants.” The plates were buried along with two stones of the sort used by seers in former times, referred to in the 1839 account as Urim and Thummim, which would enable him to translate the book. The personage instructed him to recover the plates, allowing him to see where they were buried so clearly that he recognized the place when he visited it the next day. Although he was able to find and see the plates, he was forbidden by the messenger to remove them and was told to return every year until the time came to retrieve them.

In September 1827, four years after the discovery of the golden plates and almost exactly nine months after his marriage to Emma Hale, he was finally able to recover them. Others were so eager to take them from him that Joseph and Emma took the plates to Harmony, Pennsylvania, where her family lived, to begin the work of translating them. Martin Harris, a relatively well-to-do farmer who lived near Palmyra, soon joined them to help with the translation. In mid-June 1828, two months into the translation process, Harris asked Smith to ask the Lord for permission to take the writings home to show them to his wife, Lucy. While he was in Palmyra, the initial 116 pages disappeared and were never recovered. Smith completed the translation with the help of Oliver Cowdery, who arrived in Harmony in April 1829, and the three of them moved to Fayette, New York, in June 1829, to the home of David Whitmer, where they completed the translation later that month. Also in June 1829, Smith received a revelation indicating that three witnesses would be allowed to see the plates directly—Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris. Their testimony, along with the testimony of eight additional witnesses, was included in the Book of Mormon when it was published in March 1830, and was followed by the founding of the restored Church of Christ a month later.

KEY COLLABORATORS

The Smith family, comprised of Joseph Smith Jr. (1805–44), his parents, Joseph Smith Sr. (1771–1840) and Lucy Mack Smith (1775–1856), and his siblings—particularly Alvin (1798–1823), Hyrum (1800–1844), Samuel (1808–44), Sophronia (1803–76), William (1811–93), Katherine (1813–1900), and Don Carlos (1816–41)—collaborated in bringing forth the Book of Mormon and establishing the church. Joseph Smith Sr. married Lucy Mack in Tunbridge, Vermont, in 1796, where he was a member of the Universalist Society. They and their children moved from Vermont to Palmyra, New York, in 1816, living there and in neighboring Manchester Township until 1831. Lucy Mack Smith, along with Hyrum, Samuel, and Sophronia, joined the Presbyterian Church of Palmyra in the mid-1820s.

Emma Hale Smith (1804–79), the daughter of Isaac Hale and Elizabeth Lewis, was born in Harmony, Pennsylvania, where she and her family belonged to the Methodist Church. She married Joseph Smith Jr. in January 1827. Emma and Joseph Smith Jr. initially settled in Manchester near his parents. With Emma’s help, Joseph recovered the golden plates in September 1827. In December 1827, they moved to her parents’ farm in Harmony, Pennsylvania, where Emma assisted in the translation of the plates.

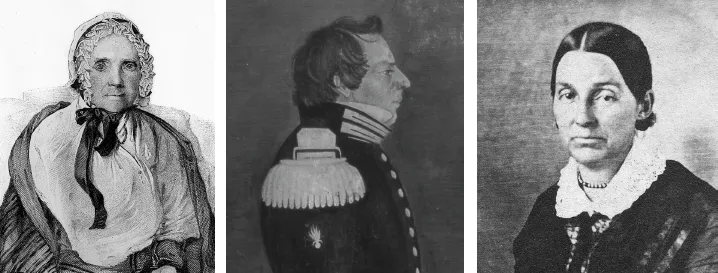

FIGURE 1.1. Lucy Mack Smith (left), Joseph Smith (center), Emma Hale Smith (right). LMS image © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Martin Harris (1783–1875) moved with his parents to Palmyra, New York, in 1793. He married his first cousin, Lucy Harris, in 1808, and together they farmed some 320 acres in Palmyra. He was religiously unsettled—reportedly investigating many denominations—before deciding to assist Smith with “the Lord’s work” in December 1827. In February 1828, he shared copies of the Book of Mormon characters with experts and assisted Smith with the translation from mid-April to mid-June 1828 in Harmony, Pennsylvania. In June 1828, he took the first 116 pages to Palmyra to show his wife, at which point the pages disappeared. In the wake of the loss, Harris remained in Palmyra and translation was discontinued. Harris visited Harmony again in March 1829, was one of the three witnesses to the gold plates in June 1829, and helped pay for the printing of the Book of Mormon. He and his wife were separated in June 1830.

Oliver Cowdery (1806–50) was born in Vermont and raised as a Congregationalist. He moved to western New York in the mid-1820s. He taught school in Manchester, New York, in 1828–29, at which time he heard about the golden plates from Lucy and Joseph Smith Sr. He traveled to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in April 1829 and served as principal scribe for most of the Book of Mormon.

Joseph Smith Jr. and Oliver Cowdery baptized each other in May 1829, and baptized Hyrum and Samuel Smith in June 1829. They baptized Joseph Smith Sr., Lucy Mack Smith, and Martin Harris in April 1830 and Emma Hale Smith, William Smith, Katherine Smith, Don Carlos Smith, and probably Sophronia Smith in June 1830. The six original members of the church (founded in April 1830) were all drawn from this group, as were two of the three witnesses to the golden plates (Oliver Cowdery and Martin Harris) and three of the eight witnesses (Joseph Sr., Hyrum, and Samuel) in June 1829. They all moved to Kirtland, Ohio, in 1831.1

SOURCES AND BEGINNINGS

Although the LDS Church follows this 1839 account and begins its history with Smith’s first vision, believers in the early 1830s began the story not with the first vision but with the discovery of the golden plates in 1823.2 This starting point is assumed in the accounts of Smith’s close associate, Oliver Cowdery, and the church’s first historian, John Whitmer (JSP, H1:6) and, in the words of LDS historians, records predating 1832 “only hint at JS’s earliest manifestation” (JSP, H1:6). That the starting point shifted over time should not be surprising. By all accounts, Smith claimed access to continuing revelation, and on this basis, he and others edited and revised both their histories of the church and the revelations allegedly vouchsafed to Smith. This process of revising in light of new revelation means that, although early Mormonism is richly documented, most of the accounts of unusual experiences are embedded in layers of interpretation. To reconstruct the process through which this new church emerged, we need to peel back layers of later interpretation to reconstruct how those involved in the process viewed events and understood their experiences as they unfolded.

The Joseph Smith Papers Project, which is publishing critical editions of texts related to Joseph Smith, is providing scholars with access to the earliest known versions of texts, along with subsequent emendations and revisions. This massive undertaking makes it possible for historically minded scholars to approach the emergence of the movement in a new way. Rather than attempting another chronological narrative premised on reconstructing a plausible beginning, we can start with the earliest period for which we have real-time sources and work our way forward and back in time, focusing on questions of interest, in this case, the role of unusual experiences in the emergence of the movement.

If we take the earliest sources as our starting point, they focus our attention on the late 1820s, that is, on the period during which the plates were being translated (Calendar of Documents, in JSP, D1:391–428). These include:

• 1825, 1 November, Agreement of Josiah Stowell and Others (including Joseph Smith), Harmony Township, Susquehanna Co., PA (authenticity not confirmed; JSP, D1:345–52; see also EMD 4:407–13).

• 1826, a court record that predates the recovery of the plates (not extant; for a discussion of later versions, see EMD 4:239–56).

• 1827, copies of Book of Mormon characters, Harmony Township, PA (not extant; for a discussion of later versions, see JSP, D1:353–67).

• 1828, reference to a (now missing) letter written by Joseph Smith Jr. to Asahel Smith (see EMD 1:553); Revelation, July 1828 (JSP, D1:6–9 [D&C 3]).

• 1829, a letter from Jesse Smith to Hyrum Smith (EMD 1:551–54); numerous revelations, February–Summer (JSP, D1:Parts 1–2 [D&C 5–10, 11–16, 17–18, 19]); the manuscript of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Mormon copyright, title page, and preface (JSP, D1:58–65, 76–81, 92–93); and the testimony of the three and eight witnesses (JSP, D1:378–87).

• 1830, the published Book of Mormon; another court record (original not extant, reprinted in the New England Christian Herald, 7 November 1832 [facsimile ed., Signature Books]); the Articles and Covenants (April, JSP, D1:116–25); numerous revelations, April–December (JSP, D1:Parts 3–4 [D&C 21–37]); and the vision of Moses (June, JSP, D1:150–55).

The most extensive documentation of this early period is provided by the revelations received during the process of translation (1828–29), which were transcribed in two manuscript revelation books between 1830–31 and published in the Book of Commandments (1833) and the Doctrine and Covenants (D&C; 1845), and by the text of the Book of Mormon itself, read in the order in which it was most likely dictated.3 Apart from the 1825 agreement with Josiah Stowell and the 1826 court record, both of which are preserved in later versions, we have no real-time access to events until July 1828, when D&C 3—the first real-time recorded revelation—opens a window in the wake of the loss of the first 116 pages of the manuscript. Chapter 1 thus opens with an in-depth analysis of D&C 3, read as a window on that moment rather than as it was interpreted and reinterpreted in later accounts.

In reconstructing these events, we do not have to limit ourselves to the perspectives of insiders. Although insiders generated most of the early realtime documentation, we have a few early sources that offer a more skeptical perspective: Jesse Smith’s 1829 letter to Joseph’s brother Hyrum and the transcripts of the 1826 and 1830 court cases that involved Smith. We also have numerous later accounts from both b...