![]()

1

The Tyranny of Litanies

In some African cities, traffic police who engage in petty corruption by routinely stopping motorists to obtain cash from them are known for their ability to come up with endless justifications for doing so. The goal of these rogue cops is not to catch bad drivers who commit traffic violations but to find ways to squeeze money from whomever they stop. After randomly pulling motorists over and checking first that they do not have political connections or are not a high-level authority, they search for an infraction with which to cite the driver—if the driver is unwilling to give them cash. They usually start by requesting the registration and insurance for the vehicle. If this paperwork is in order, they will not hide their discontentment. They then request the driver’s license. Again, they will not conceal their displeasure if the driver is able to provide a valid license. They then must find something else to justify a citation. After they go through a list of other nonmoving violations or infractions (defective or improper vehicle equipment, seat belt or child-restraint safety violation, etc.), their logical next request is to ask to see the pharmacy box. Yes, in many countries motor vehicles on the road are required to have a pharmacy box. No one knows what it must legally contain, and rogue police use its absence as an excuse to issue a traffic ticket.

Some motorists heroically resist complying with such extortion and are well prepared for encounters with the police by keeping a pharmacy box in their car. When confronted with such drivers the disgruntled police ask a final, unanswerable question: “Can you prove that you were driving at the appropriate speed limit when I pulled you over?” adding with a sarcastic smile, “I stopped you because you were driving too fast!”

In such bad-luck situations it is impossible to escape punishment. The only remaining question is whether the motorist will choose to play the game, plead guilty to a phony charge, and pay the bribe or will pursue the heroic fight to prove compliance with laws and regulations. If the motorist wishes to contest a traffic infraction, the police will take away the vehicle’s registration and promise a hearing to be set by the court. The hearings are supposed to take place before a magistrate or judge. Of course, no motorist wants to take the chance of relinquishing important documents to rogue police, so the rational (less risky and frankly less costly) option is to plead guilty to whatever traffic violation the driver is being accused of and then make a deal with the police, often in the form of a couple of dollars paid as a ransom to avoid further harassment.

The discourse on economic development is often reminiscent of this kind of uneven interaction. When asked why only a handful of countries have managed to perform well since the Washington Consensus policies were launched in the 1980s, many experts tend to behave like the rogue police on the streets of Africa. They offer ever-changing explanations that they present as irrefutable truths. Defending their intellectual agenda even in the midst of obvious failure and disappointments, they come up with a litany of reasons for the failure of their prescriptions—typically a wide range of reasons about poor implementation—that policy makers in developing countries cannot dispute. This justification strategy of constantly putting the blame on the recipient allows the proponents of the Washington Consensus to require further compliance by poor countries. Like the helpless motorists on some African streets, policy makers must accept whatever recommendations are imposed on them.

Of course, it would be unfair to characterize the honest but difficult search for answers that motivates most development economists and experts as equivalent to the immoral and illegal behavior of renegade police. But the fundamental tactics often used to justify a predetermined and liturgical discourse and to enforce a priori decisions are similar. They are often based on false diagnostics and rely on rhetorical sophisms. This is why policy makers in low-income countries often confess that they constantly feel pressure from powerful development experts whose opinions carry weight and can determine whether a small economy has access to external funding. In many such countries, Washington Consensus policies still represent the dominant intellectual framework for policy analysis and justify all prescriptions for reforms (Monga and Lin 2015; Mkandawire 2014; Mkandawire and Soludo 1999; Mkandawire and Olukoshi 1995). Questions about the sources of low growth, low employment creation, and persistent poverty are given successive answers that are meant only to reflect and validate a predetermined truth. After trying in vain to offer alternative views of the problems of development, government officials find themselves in the same situation as the African motorists. The opportunity cost of asserting different opinions and of taking the chance to pursue different strategies is simply too high. It becomes rational to just go along with the prevailing truth and conventional thinking—and to accommodate policies that have little chance of yielding the expected positive results.

This chapter examines some of the policy issues often presented as the causes of poor economic performance and underdevelopment. It identifies the most commonly posited causes—insufficient physical capital, bad business environment and poor governance, weak human capital and absorptive capacity, low productivity, and bad cultural habits (laziness)—and explains why they are inconsistent with both the historical and the empirical evidence.

INFRASTRUCTURE: A REAL CONSTRAINT BUT A CONVENIENT CULPRIT

The most common policy precondition given by many economists for improved economic performance in developing economies is the quantity and quality of infrastructure. Since at least Adam Smith, economists have known that transport infrastructure plays an important role in economic growth and poverty reduction. Starting with the work of D. Aschauer (1989), B. Sanchez-Robles (1998), and D. Canning (1999), researchers have offered compelling theoretical and empirical analyses to support infrastructure’s role. While the empirical arguments about the specific conditions under which infrastructure is beneficial are far from being fully settled, there is broad consensus that under the appropriate conditions, infrastructure development can induce growth and equity, both of which contribute to poverty reduction. Infrastructure services increase total factor productivity (TFP) directly because they are an additional production input and have an immediate impact on enterprises’ productivity. Indirectly they can raise TFP by reducing transaction and other costs, thus allowing a more efficient use of conventional productive inputs. In addition, infrastructure services “can affect investment adjustment costs, the durability of private capital and both demand for and supply of health and education services. If transport, electricity, or telecom services are absent or unreliable, firms face additional costs (e.g., having to purchase power generators), and they are prevented from adopting new technologies. Better transportation increases the effective size of labor markets” (Dethier 2015).

It is conventional wisdom that all economies rely heavily on various types of infrastructure and investments to improve conditions and performance and to move people and goods more efficiently and safely to local, domestic, and international markets. All countries need effective transport, sanitation, energy, and communications systems if they are to prosper and provide an adequate standard of living for their populations. Decent roads, railways, seaports, and airports are essential for the sustainable growth of key industries such as agriculture, industry, mining, or tourism—particularly important in developing economies. Good transport infrastructure improves the delivery of and access to vital social services such as health and education. Without a well-functioning transport system, much activity in most countries would grind to a halt.

Transportation infrastructure has substantial economic benefits in both the long and the short run. Investments that create, maintain, or expand road and railway networks can improve economic efficiency, productivity, and economic growth. These investments can also support employment in construction and in the production of materials, with the increased spending by the workers hired in these sectors generating positive ripple effects throughout the economy. The short-run effects can vary depending on the state of the economy. At the peak of a business cycle, when the economy is operating at or close to full potential, the benefits of hiring workers for infrastructure projects could be partially offset by the diversion of these workers from other productive activities, and the investment of public funds may “crowd out” some private investment (EOP 2011). But economies around the world are generally operating significantly below their full potential, with underemployment and unemployment still high. In such excess-capacity situations there is little risk that increased spending on construction materials and increased private spending by newly hired workers will divert goods or materials from other uses. In fact, with large amounts of resources sitting idle, the opportunity costs of using them for infrastructure investment are greatly reduced. Therefore the value of making such investments is high at a time when the global economy continues to have substantial underutilized resources, including more than 200 million workers seeking employment.

Yet many developing countries suffer from a large infrastructure deficit, which hampers their growth and ability to trade in the global economy. Asia still demonstrates a massive gap in infrastructure funding.1 The situation in Latin America and the Caribbean is no better. César Calderón and Luis Servén (2011) compare the evolution of infrastructure availability, quality, and accessibility across the region with that of other benchmark regions. They focus on telecommunications, electricity, land transportation, and water and sanitation. Overall they find evidence that an “infrastructure gap” vis-à-vis other industrial and developing regions opened up in the 1980s and 1990s. They also estimate the quantitative growth cost of the region’s infrastructure gap.

Africa’s infrastructure challenges are even more daunting. Compared with other regions, Africa has a low infrastructure stock, particularly in energy and transportation, and the continent has not fully harnessed its information and communication technology potential. Inadequate infrastructure raises the transaction costs of business in most African economies. Studies by the African Development Bank estimate that inadequate infrastructure shaves off at least 2 percent of Africa’s annual growth, and that with adequate infrastructure, African firms could achieve productivity gains of up to 40 percent. The situation is particularly worrisome in the agriculture sector. Calestous Juma (2012) notes:

A large part of the continent’s inability to feed itself and stimulate rural entrepreneurship can be explained by poor infrastructure (transportation, energy, irrigation, and telecommunication). The majority of Africa’s rural populations do not live within reach of all-season roads. As a result they are not capable of participating in any meaningful entrepreneurial activities. On average, in middle-income countries about 60 percent of rural people live within two kilometers of an all-season road. In Kenya … only about 32 percent of the rural people live within two kilometers of an all-weather road. The figure is 31 percent for Angola, 26 percent for Malawi, 24 percent for Tanzania, 18 percent for Mali and a mere 10.5 percent for Ethiopia.

Unfortunately, too many experts draw the wrong conclusions from these diagnostics. Identifying a problem correctly does not necessarily translate into a good understanding of its meaning and implications. One should be careful not to misinterpret Albert Einstein’s admonition, “If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend fifty-five minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” While the infrastructure gap must be resolved, it is a mistake to postulate—as many development experts do—that it necessarily prevents developing countries from initiating a process of sustained economic growth.

Poor infrastructure is indeed a major binding constraint on economic performance, but it is not an insurmountable barrier for launching economic transformation, especially with today’s globalized economies, decentralized global value chains, increasingly freer trade, mobile capital flows, and migration of skilled workers. Economic development and infrastructure building can evolve in parallel and feed each other. No country in human history started its process of economic development with good infrastructure—certainly not Great Britain in the late eighteenth century, the United States in the early nineteenth century, or China in the late twentieth century, where there was only a very small network of highways. Yes, Africa’s infrastructure gap is a major bottleneck to economic growth and welfare. But it is a mistake to expect that economic development can be launched successfully only after that gap is filled—in fact, it may never be filled, even when the continent’s annual GDP per capita reaches $100,000. Infrastructure development and maintenance are matters of constant concern for policy makers—even high-income countries need continuous industrial and technological upgrading.2

Moreover, by assuming that the infrastructure gap is the culprit for poor economic performance and that it should be resolved before sustained growth can take place, many experts and policy makers tend to adopt generic, costly, and unrealistic solutions to the problem. Asia’s overall national infrastructure investment needs are estimated to amount to $8 trillion over the 2010–2020 period, or $730 billion per year—68 percent of which is for new capacity and 32 percent for maintaining and replacing existing infrastructure (ADB/ADBI 2009; The Global Competitiveness Report 2011–2012). These are staggering numbers. India’s infrastructure needs for the next decade are estimated to vary between $1 trillion and $2 trillion. Africa’s infrastructure gap is estimated to amount to $93 billion per year (Andres et al. 2013). In South Africa alone, a country considered the most industrialized on the continent, infrastructure needs are still so large that the government unveiled in 2012 a three-year, $97 billion plan to upgrade roads, ports, and transportation networks aimed at accessing coal and other minerals. That is more than the combined annual GDP of Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Mozambique.

By approaching economic growth as a linear and teleological process in which all infrastructure constraints must be addressed before positive dynamics can take place, proponents of the Washington Consensus have generally recommended policy reforms that amount to privatizing the infrastructure sector and devoting more public and private money to it (Foster and Briceño-Garmendia 2010). Such recommendations, which involve untargeted policies and broad reform programs that are often politically difficult to implement, may or may not yield positive results.

The inadequacy of the broad infrastructure policies recommended to developing countries mirrors the unrealistic and daunting reform programs prescribed in the Washington Consensus framework. No country with limited financial and administrative resources should be expected to seriously adhere to the long list of reforms identified as conditions for generating economic growth. Each reform may or may not make sense individually. Without prioritization, these dozens (if not hundreds) of difficult policy prescriptions are politically unfeasible and certainly do not reflect the real, binding constraints in potentially competitive industries. This is why successful developing countries typically do not blindly follow them. The puzzling inconsistencies in the Doing Business rankings are evidence that the recommended reforms are problematic. Several of the top-performing countries in the world for the past twenty years are consistently ranked quite low when it comes to the ease of doing business: Brazil is 132nd, Vietnam 98th, and China 91st, behind such star economies as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Tunisia, Belarus, and Vanuatu (Doing Business 2013).

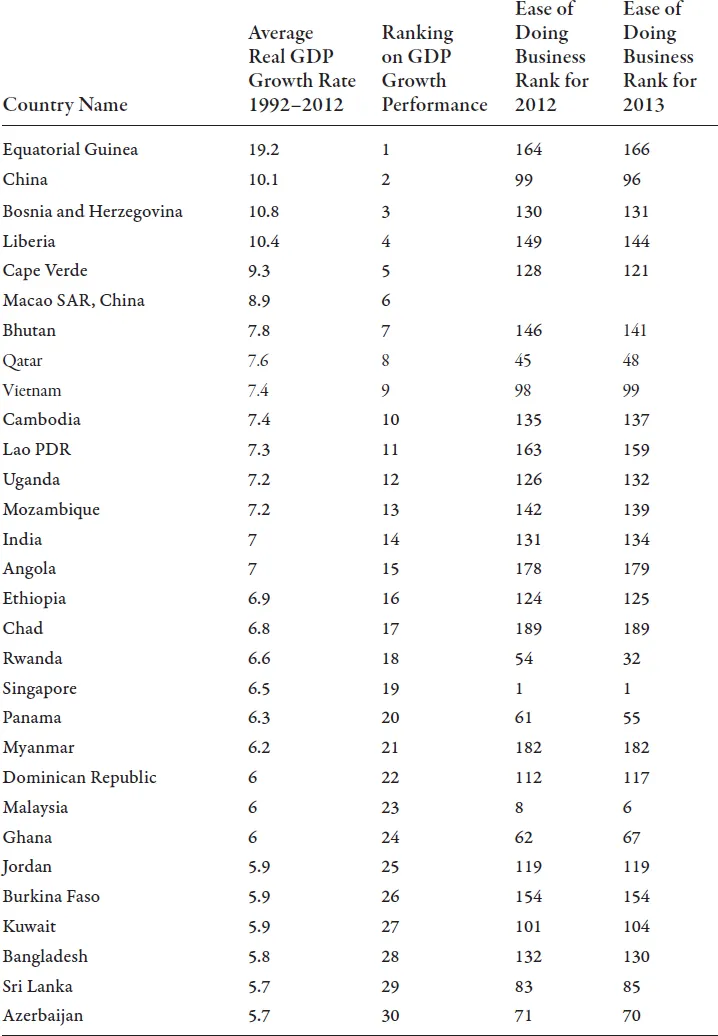

Table 1.1, which lists the thirty fastest-growing economies of the past two decades, provides evidence that the quality of the business environment, at least as measured by popular indicators, does not seem to matter: except for Singapore and Malaysia, the remaining economies score rather poorly on the Doing Business indicators.

A more pragmatic approach is to focus the government’s limited resources and implementation capacity on the creation of “islands of excellence,” or carefully selected areas with good infrastructure and business environment (even in countries with a poor overall infrastructure and business climate), to facilitate the emergence of competitive industries—those that exploit the economy’s latent comparative advantage.3

TABLE 1.1. STELLAR ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE IN A POOR BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT: THIRTY FASTEST-GROWING ECONOMIES IN THE WORLD, 1992–2012 GDP GROWTH PERFORMANCE EASE OF DOING BUSINESS RANK FOR 2012

Source: Authors’ calculations.

REALITIES AND MYTHS OF A WEAK HUMAN CAPITAL BASE

If, despite its importance and relevance, the infrastructure gap is not a constraint that completely prevents economic growth from taking place in low-income countries, then what is the problem? Following the logic of the rogue police on the streets of Africa, the most obvious suspect should be human capital (generally defined as “the knowledge, skills, competencies, and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being”4), and for very good reasons: human capital is indeed generally weak in developing nations.

Human capital theory, which emerged in the early 1960s, argues that schooling and training are investments in skills and competences and that individuals make decisions on the education and training they receive as a way of augmenting their productivity—a rational expectation of returns on investment (Schultz 1960, 1961; Becker 1964). Subsequent studies have explored the interaction between the education and skill levels of the workforce and technological activity, explaining how a more educated/skilled workforce allows firms to adopt and implement new technologies, thus reinforcing returns on education and training (Nelson and Phelps 1966). James Heckman (2003, 796–97) explains how human capital improves productivity:

First of all, human capital is productive because of its immediate effect on raising the skill levels of workers. So, for example, if an individual is trained to be a better accountant, the accounting performance of that individual will rise. If a worker is trained to fix an engine, the worker will be more productive in fixing engines. These are the obvious direct effects of making people more skilled. But human capital also improves the adaptability and allocative eff...