![]()

CHAPTER 1

THREE CRISES AND AN OUTCOME

THE CHOICE AMONG ALTERNATIVES

Every generation gets the history it needs. Fashions come and go; some reappear, suitably restyled, long after their original incarnation has been forgotten. The historiographical record indicates that previous trends have boomed for a decade or so before subsiding. The branch of the subject that deals with imperial and global history illustrates the oscillations of the last half century with particular clarity. Modernization theory, which was profoundly ahistorical, gave way to the dependency thesis, which tempted social scientists to embrace the past with unguarded passion. Marxism corrected the over-flexible radicalism of the dependency thesis by reasserting the paramountcy of production over exchange. Postmodernism inverted the prevailing hierarchy of causes by elevating the ideal over the material. Today, historians have resurrected the “totalizing project” and are busily globalizing continents, empires, and islands.

The changing mood of the profession obliges scholars to find their place among shifting priorities. If they fail to move with the times, they risk being trapped, as Marxists used to say, in an “outdated problematic.” If they follow fashion, they are in danger of losing their individuality. Those who buy stock at the outset do well. Those who join when the market is at its peak suffer in the collapse that follows. Each fashion appeals because it offers a seemingly comprehensive response to a pressing current issue. Each ends when it is laid low by contrary evidence or is beaten into submission by incessant repetition. After the event, it becomes clear that the issue of the day was not, after all, the riddle of the ages.

The ability to anticipate the next phase of historical studies would greatly ease the difficulty of choosing priorities. Unfortunately, past performance, as financial advisors are obliged to say, does not guarantee future returns.1 Nevertheless, historians can still use their knowledge of previous and current priorities to help configure their work. It would be unwise, for example, to assign globalization a central place in the interpretation advanced in the present book without recognizing that the term now has a prominent, indeed almost mandatory, place in publications written by historians.2 Similarly, empire studies have enjoyed a revival that has been stimulated by the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the further rise of the United States, which commentators regard as the superpower of the day, notwithstanding the sudden appearance of China.3 Accordingly, there is now a danger of repeating a message that has already been received. Once the boredom threshold is crossed, the latest approach becomes redundant. There is a risk, too, of being caught handling an outdated problematic when the mood of the moment changes. If hostility toward globalization gathers momentum, scholars may shift their attention to alternatives, such as nation-states. At this point, however, it is necessary to keep a steady hand, recalling, with Oscar Wilde, that “it is only the modern that ever becomes old-fashioned.”4

Appearances to the contrary, however, the current problematic has not yet passed its sell-by date. Although the “global turn” has attracted the attention of scholars, it has made only a limited impression on the curriculum, which remains resolutely national.5 Moreover, publications that respond to the demands of fashion often have more appeal than substance. Some authors have inserted “global” in the titles of books and articles to achieve topicality and add theoretical weight to otherwise orthodox empirical narratives. Others have raised the term to macro-levels that are superficial rather than insightful. As yet, few historians have connected their work to the relevant analytical literature in ways that command the attention of other social scientists.

Despite these weaknesses, which are common to all historiographical trends, there have also been significant advances. Pioneering work during the last decade has established a powerful case for enlarging standard treatments of U.S. history by supplying it with an international context.6 Research on the non-Western world has shown that globalization had multicentered origins, and was not simply another long chapter in the story of the Rise of the West. Similarly, the realization that globalization can create heterogeneity as well as homogeneity has had the dual effect of showing how localities contributed to global processes and how supranational influences shaped diverse national histories.7 Other work has opened routes to the past that have yet to be explored. One key question is whether the history of globalization is the record of a process that has grown larger with the passage of time without fundamentally changing its character, or whether it is more accurate to see it as the evolution of different types in successive sequences.8 The latter position provides the overarching context for the interpretation advanced in this study, which identifies three phases of globalization and explores the dialectical interactions that transformed them.

The renaissance of empire studies has also left some central questions unresolved. Historians have wrestled with the problem of defining an empire for so long that it is unlikely they will ever agree on a formula that commands majority assent. Contributions to the literature by other commentators have now widened the application of the term to the extent that exchanges are often at cross-purposes. Comparisons are particularly vulnerable to definitional differences. If the term “empire” is used in a very broad sense to refer to great states that exercised extensive international powers, numerous comparisons can be made through time and across space. However, if the characteristics of the units chosen for comparison differ in their essentials, conclusions about commonalities are likely to be invalid. If the definition is narrowed to suit a particular purpose, potential comparators may fail to qualify, and the resulting study treats singularities without also being able to identify similarities. The definition adopted here, and discussed later in this chapter, tries to steer a course between these pitfalls. The hypothesis that empires were globalizing forces provides a basis for establishing their common purpose. The argument that globalization has passed through different historical phases anchors the process in time and suggests how the history of the United States can be joined to the history of Western Europe, and indeed the world.

The current interest in globalization has had the unanticipated benefit of allowing economic history to re-enter the discussion of key historical issues. Postmodernism and the linguistic “turn” gave historians a new and welcome focus on cultural influences but also reduced their interest in the material world. Today, there is a renewed awareness of the relevance of economic history, but a shortage of practitioners.9 By reintegrating economic themes, the present book hopes to alert a new generation of researchers to the prospects for contributing to aspects of the past that have been neglected in recent decades. This is not to say that economics should be regarded as the predominant cause of great historical events, as specialists can easily assume. As conceived here, globalization is a process that also incorporates political, social, and cultural change. This comprehensive approach to the subject underlies the interpretation of the present study and the chronology derived from it.

A consideration of empires as transmitters of globalizing impulses reveals a further dimension of the past that recent versions of imperial history have yet to incorporate, namely indigenous perspectives on the intrusive Western world.10 With the rise of Area Studies in the 1960s, the old-style imperial history with its focus on white settlers and rulers gave way to new priorities, which concentrated on recovering the indigenous history of parts of the world that had recently gained political independence. Although this work has continued its remarkable advance, it has done so principally by creating separate regional specialisms. The new imperial history, on the other hand, has tended to take a centrist view of empire-building, while exploring topics such as the expansion of the Anglo-world, the creation of racial stereotypes, and the formation of gender roles. The position taken here seeks to integrate the standpoint of the recipients of colonial rule. It will become apparent that the story is not simply one of “challenge and response” but of interactions among interests that were drawn together by the absorptive power of global processes. Globalizing impulses were multicentered. Islands, including those colonized by the United States, were not merely backwaters serving as minor recipients of much larger influences, but cosmopolitan centers that connected entire continents with flows of goods, people, and ideas.11 They were both turnstiles and manufacturers of globalization. What entered was often processed and altered before it exited. This degree of creativity ought not to be surprising. Borderlands and islands are typically more fluid and often more innovative than established centers, where hierarchy predominates and controls are more readily exercised.

This study combines global, imperial, and insular approaches to compose a history of the United States that builds on, but also differs from, those currently on offer, principally by describing a view from the outside in, rather than, as is more usual, from the inside out.12 As large claims readily confound those who make them, it is wise to take insurance against the possibility of misfortune. One exclusion clause covers the scope of the book, which does not deal with the totality of U.S. history but with those features judged to be most pertinent to empire-building and decolonization. Accordingly, domestic politics feature principally at the federal level in the nineteenth century, when external influences, especially those from Britain, made themselves felt, but only to a limited extent in the twentieth century, when the United States had gained full control of its own affairs. Other important themes, such as Native American history and the history of borderlands, appear only in relation to issues that directly pertain to the subject examined in this study. Fortunately, these topics and others not mentioned here are being given the prominence they deserve in new accounts of the national story.

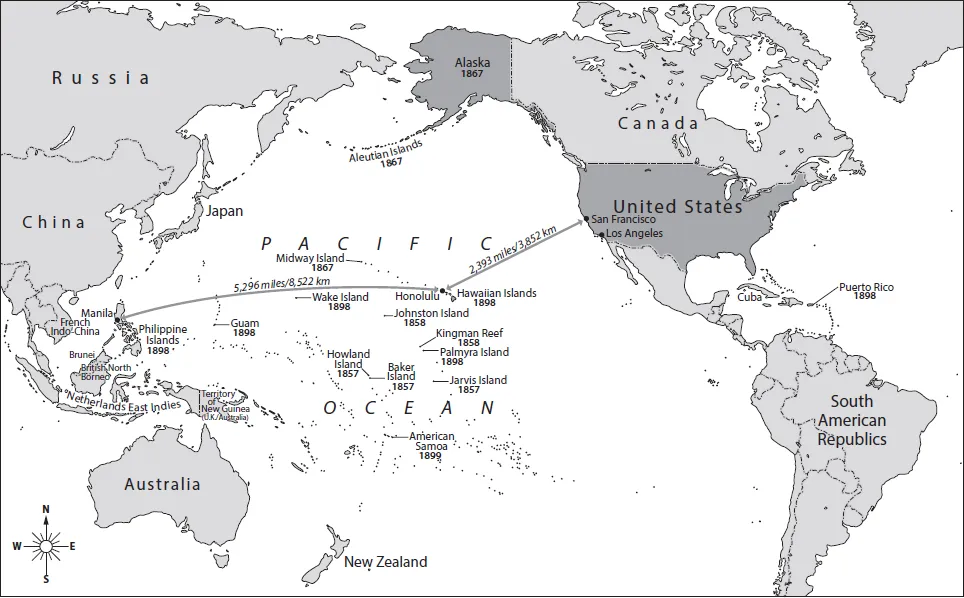

A further limit concerns the recipients of U.S. imperialism. The empire considered here is the insular empire acquired after 1898. In 1940, the U.S. Bureau of the Census listed thirteen inhabited overseas territories, which, with Alaska, had a population of 18,883,023.13 The great majority were islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. Almost 99 percent of the total population was located in the Philippines (16,356,000), Puerto Rico (1,869, 255), and Hawai‘i (423,330). These three islands, together with Cuba, form the basis of the U.S. territorial empire considered here. Cuba, which had a population of 4,291,100 in 1940, has been included as an example of a protectorate. The Open Door and dollar diplomacy are not explored in detail, though they undoubtedly merit further examination. One problem arises from the amorphous character of informal influence and the difficulty of tracking it geographically and chronologically. A more prosaic obstacle is that the space required to treat the subject adequately would turn a large study into a forbidding one. On the other hand, the restricted treatment of this theme in the early twentieth century has allowed room for a discussion of U.S. power in the world after 1945, when the debate on informal empire and hegemony imposes itself in a manner that is so weighty as to be unavoidable.

MAP 1.1. The U.S. Insular Empire.

BEYOND “THE NATIONAL IDEOLOGY OF AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM”14

The emphasis placed here on the global setting requires a reappraisal of the strong national tradition that has long formed the basis of historical studies in the United States, as it has in other independent states. National traditions of historical study arose in the nineteenth century to accompany (and legitimate) new nation-states, and they remain entrenched today in programs of research and teaching throughout the world. The tradition has many admirable qualities that need to be preserved. However, it no longer reflects the world of the twenty-first century, which is shaped increasingly by supranational influences. The national bias can also produce distortions, which are expressed most evidently in the belief that what is distinctive is also exceptional rather than particular. The conviction that the United States had, and has, a unique providential mission has helped to form the character of American nationalism and the content of U.S. history. What the literature refers to as exceptionalism retains a strong grip on popular opinion and continues to influence foreign policy, as it has done since the nineteenth century.15

The persistence of a historiographical tradition that is still largely insular ensures that the case for American exceptionalism is largely self-referencing.16 The consequence is a failure to recognize that distinctiveness is a quality claimed by all countries. Some form of providentialism invariably accompanies states with large ambitions. A sense of mission produces a misplaced sense of uniqueness, which, when allied to material power, translates readily into assumptions of privilege and superiority.

Comparisons, as Marc Bloch pointed out in a classic essay, supply a more convincing means of testing historical arguments than do single case studies.17 The claim that a particular nation is “exceptional” is demonstrated, not by compiling self-descriptions of the nation in question, but by showing that other nations do not think of themselves in the same way. The common procedure, however, is to ignore competing claims as far as possible and, if challenged, to assert the principle of ideological supremacy.

Yet, Russia’s rulers have long attributed semi-divine status to the state and assumed that their purpose is to deliver a special message to the world.18 The French believe that they are the chosen guardians of a revolutionary, republican tradition. For the historian and patriot, Jules Michelet, the revolution that made France was itself a religion.19 The concept of l’exception française endowed la grande nation with the duty of carrying la mission civilisatrice to the rest of the world.20 The poet and philosopher Paul Valéry considered that “the French distinguish themselves by thinking they are universal.”21 They were not alone in this belief, even if Valéry was unaware of the competition. Spanish writers have long discussed their version of excepcionalismo. Scholars have traced Japan’s sense of distinct cultural identity, Nihonjinron, to the eighteenth century, and discovered elements of it long before then. German theorists devised “den deutschen Sonderweg” in the late nineteenth century to describe their own country’s special path to modernity.22 The British, unsurprisingly, had no doubt who had reached the summit of civilization first. “Remember that you are an Englishman,” Cecil Rhodes advised a young compatriot, “and have consequently won first prize in the lottery of life.”23

It needs to be said at once that few professional historians, as opposed to members of the public, still subscribe to an undiluted notion of exceptionalism. As some historians have made progress in placing U.S. history in a comparative context, so others have amplified and qualified the founding national saga by ...