This is a test

- 98 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In Nepal, deeply embedded structural conditions determined by gender, caste or ethnicity, religion, language, and even geography have made access to and benefits from energy resources highly uneven. Women, the poor, and excluded groups experience energy poverty more severely. To address this imbalance, the government and other stakeholders have introduced measures to achieve greater gender equality and social inclusion. This study is an attempt to understand the factors affecting the outcomes and extent to which the initiatives have fostered gender equality and social inclusion. The study recommends measures to facilitate the distributive impact of energy sector development if Nepal is to meet its target of ensuring energy access to all.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Assessment of the Energy Sector by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

There is a considerable energy divide in the world—between rich and poor countries; within countries, with the rich benefiting the most from energy resources; between urban and rural areas; and within households.1 Addressing these gaps has become crucial, especially since the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 7 (ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all) recognizes that energy is central to progress in all areas of development.2 However, in the context of Nepal, as in many other South Asian countries, deeply embedded structural conditions determined by gender, caste or ethnicity, religion, language, and geography to name a few have meant that access to, as well as benefits from, energy resources flow are unequal, with women, the poor, and people from excluded groups experiencing energy poverty differently and more severely than those from relatively advantaged groups.3

To address these challenges, the government, development institutions, and civil society groups have introduced policies and programs in Nepal. However, the extent to which these measures have brought transformative changes in the lives of the local population, especially women, the poor, and the marginalized remains to be determined. Further, the twin pressures of expanding energy resources to meet Nepal’s ambitious growth agenda, for which energy is crucial, and ensuring energy access to all, including addressing the distributive impact of energy sector development, provide an additional challenge.

This study seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) issues of the energy sector.

1.1 Research Context: Energy Development in Nepal

1.1.1 Energy Resources

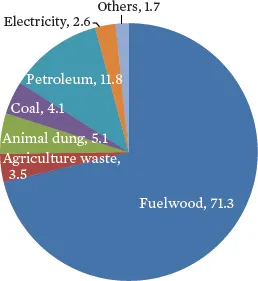

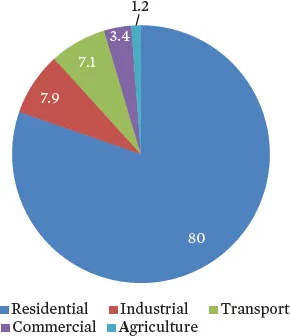

The Government of Nepal has classified the country’s energy resources into three: (i) traditional (fuelwood, agricultural residue, and animal dung); (ii) commercial (energy supplied by grid electricity, coal, and petroleum products); and (iii) alternative (biogas, solar power, wind, and microhydropower).4 The latest available data show that 80% of the country’s energy comes from traditional sources (Figure 1.1) with the bulk (80%) consumed by the residential sector (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1: Sources of Energy, 2012–2013

(%)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics. 2015. Statistical Pocket Book Nepal, 2014.

Figure 1.2: Energy Consumption by Sector, 2012–2013

(%)

Source: Water and Energy Commission Secretariat. 2014. Energy Data Sheet.

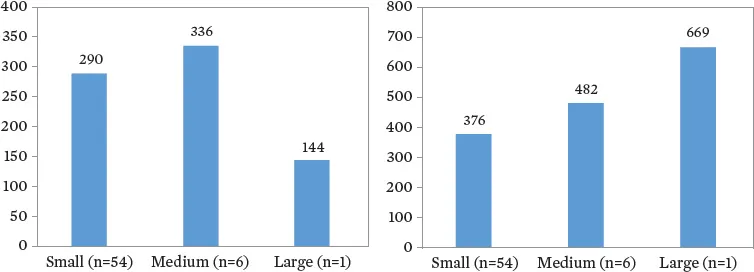

Nepal’s continued dependence on traditional sources stands in contrast to the fact that it has one of the highest per capita hydropower potentials in the world. Yet, hydropower provides less than 3% of its energy needs and has failed to deliver its potential so far.5 Figure 1.3 shows the generation capacity of hydropower projects that are currently in operation and under construction. More specifically, the hydropower potential of Nepal’s rivers is estimated to be 83,290 megawatts (MW), with 45,610 MW considered technically feasible (footnote 4).

Figure 1.3: Generation Capacity of Projects in Operation and under Construction, July 2015

(MW)

Source: Independent Power Producers’ Association, Nepal. 2015. List of Projects to be Developed by Independent Power Producers and Nepal Electricity Authority. Unpublished, updated 28 July 2015.

To provide the much-needed impetus to its economy and to address infrastructure gaps, the government is seeking major investments in infrastructure development, and the hydropower sector has emerged as a key priority area.6

As a response to continued challenges associated with the generation and expansion of the national grid, wind and solar energy have recently been identified as potential alternative sources of renewable energy, with the commercial potential of wind power estimated at 3,000 MW and of solar at 2,100 MW.7 Accordingly, the government has been providing subsidies, particularly in rural areas, to promote alternative forms of renewable energy, namely, mini-, micro-, and pico-hydropower, solar, biogas, and biomass, mainly through the Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC). As a result, there has been incremental progress in rural electrification, with AEPC reporting 20,108 rural households electrified though 2.2 MW generated by 102 micro-and pico-hydropower plants in 2012–2013, 42,875 households in 2013–2014, and 25,235 in 2014–2015, far short of a rate at which the entire population can be supplied with a reliable and uninterrupted source of energy.8 As for wind energy, there has been very little achievement, with less than 20 kilowatts of electricity generated,9 though wind–solar hybrid systems have increasingly been promoted in rural communities.10 Recent estimates suggest that 12% of Nepal’s population has access to electricity through renewable energy sources.11

1.1.2 Energy Demand, Consumption, and Distribution

Nepal’s per capita energy consumption is very low. In 2013, it was 370 kilograms of oil equivalent, two-thirds of the South Asian average of 550 kilograms of oil equivalent and a fifth of the world average of 1,894.12 Growth in energy consumption has also been slow, averaging a 2.7% annual increase during 1990–2013 compared with the regional average of 4% (footnote 12).

Further, four-fifths of the energy consumed nationally is by the “nonproductive” residential sector while the share of industry is just about 8%, indicating a suboptimal pattern of energy consumption (Figure 1.1). Yet, nearly a quarter of the population still has no access to electricity.13 One reason is that the transmission line network, extending to around 2,800 kilometers with 27 grid substations, is considered insufficient.14 This lack of adequate infrastructure is considered a major hindrance to evacuating energy from generation sites to load centers.

Complementing state efforts to expand access to electricity is the community approach, whereby rural communities purchase electricity in bulk from the state-owned electricity distribution monopoly, the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA), and resell it to its members. Since the Community Rural Electrification Programme began in 2003, some 45,000 households in 55 districts have received electricity through 480 community groups (footnote 14).

Energy demand has, however, been increasing. In 2014–2015, demand for grid electricity stood at 1,292 MW15 while supply was limited to a peak of 770 MW in the rainy season.16 Factors such as rapid urbanization are leading to this steady rise in demand that is estimated to rise by an annual average of 8.9% between 2010–2011 and 2019–2020.17 So far, the government and NEA have met the shortfall through scheduled blackouts, called “load-shedding,” and through import of power from India. In the rural areas, this has meant, as mentioned above, the continued use of traditional fuels such a fuelwood, agricultural residue, and animal waste. However, the impact of this energy scarcity for different population groups is not yet known or analyzed.

1.2 Gender Equality and Inclusion Issues in Energy Sector: Review of Existing Knowledge and Gaps

GESI has now been recognized as one of the main factors influencing development outcomes in Nepal.18 Accordingly, development policies and programs are increasingly seeking to either promote direct interventions to support GESI outcomes and mainstream GESI issues in programmatic responses, or promote GESI-sensitive policies and programs.19 While the commitment and endorsement of the GESI agenda is certainly one of the hallmarks of the current development discourse in Nepal, a knowledge gap around GESI issues continues in the energy sector, particularly about (i) how social inequities influence the outcomes in energy projects; (ii) what the differential needs of men, women, and socially excluded groups are in terms of energy services and technologies; and (iii) the nature of barriers that women and socially excluded groups experience while seeking to benefit from energy services. Likewise, questions remaining to be answered include: (i) Can and does access to energy services and technologies enhance welfare, efficiency, empowerment, and gender relations? (ii) How do issues of gender inequality and social exclusion affect certain development outcomes? (iii) What are the potential entry points for leveraging GESI issues in the energy sector to have transformative impacts?

A review of the literature on social exclusion in Nepal indicates that different excluded groups typically experience various structural barriers, including in matters relating to energy access (Table 1.1). In terms of how these barriers intersect with energy services and technologies, the evidence from Nepal and other countries is, however, limited primarily to women and the poor. In a pattern similar to other developing countries, Nepal has plenty of evidence indicating that women experience energy poverty differently and more severely than men.20 Women are responsible for fetching fuel and water for their households as well as for engaging in various types of microenterprises. Since the burden of providing energy to fulfil their household needs fall disproportionately on women who spend a significant amount of their time and effort in collecting fuel, the opportunity cost is high for them as it takes them away from employment, education, and other activities for “self-improvement” (footnote 11 and footnote 20 [Identification of Gender and Social Inclusion Gaps at Policy and Institutional Level]). Further, continued dependence on traditional biomass has detrimental effects on women’s health through indoor air pollution caused by smoke and unhealthy work places (footnote 11). Yet, socially constructed perceptions that consider modern energy as “men’s domain” limit the opportunities for women to take full advantage of new energy sources, particularly in entrepreneurship.21 Further, a study conducted by AEPC also indicates that existing income inequities also determine the ability to benefit from energy.22

Table 1.1: Structural Barriers Experienced by Different Groups

| Social Group | Nature of Barriers |

| Women | Patriarchal values; social stigma; discriminatory practices impacting women of diverse social groups; limited access to land and other economic assets; violence, including domestic violence; restrictions on mobility; limited voice and agency; and low decision-making authority |

| Janajatis | Language and culture not given due recognition, especially of the more disadvantaged Janajati groups; remoteness and geographical isolation; discrimination due to different culture, traditions, and practices; higher levels of poverty; negative perceptions about Janajati women’s comparatively higher mobilit... |

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables, Figures, Boxes, and Map

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Research Framework

- 3 Policy, Legal, and Institutional Framework

- 4 Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Features of Energy Programs and Projects

- 5 Current Situation of Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Energy Development

- 6 Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Impacts of Energy Programs and Projects

- 7 Lessons Learned and the Way Forward

- Appendix 1 Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Project Cycle

- Appendix 2 Policy and Legal Framework

- Appendix 3 Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Engineering

- Footnotes

- Back Cover