![]()

1

SEEKING INFORMATION IN DISASTER

We now live in a world of 4G news updates. The latest breaking news crisis can turn any one of us into an instant Anderson Cooper, the anchor man on the street of the next major crisis or tragedy. All we need is to phone a friend on our latest smartphone, text an “OMG!,” capture eyewitness video and stills, and finally upload it to our own YouTube channels, Facebook walls, and Twitter feeds. Instantly, we are all our own personal newsmakers. We now expect information on anything and everything—when we want it and where we want it. Yet Hurricane Katrina, in user-sharing advanced 2005, rendered 4G a 1G.

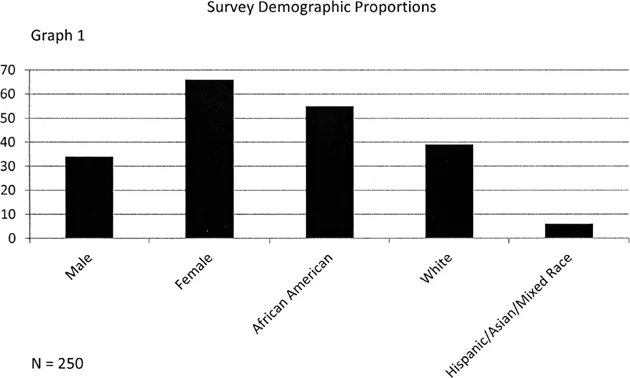

Katrina was a perfect storm of winds carrying a technology blackout. Some victims described it as “apocalyptic.” From local journalists to evacuees, cell phones and all their gadgets became useless as they scampered around a devastated city in search of working landlines, analog radios, and the small chance of a faint signal that would send a text message to anyone whose area code did not start with the dreaded 504. For scores of local journalists interviewed, and 250 victims and evacuees surveyed in the days and months after Katrina, technology in that summer of 2005 had failed them. Katrina remains a standout case study for what could happen in a technology blackout, but it is also a standout case for the coming of age of Internet journalism.

No longer a repository for rehashed print news, news organizations’ websites became local, community portals—a way to inform and engage that had never before been used at this level. Users and communicators were forced to adapt in order to send and receive life-saving information. This adaptation mimicked a spiderweb rather than a triangle, in terms of the relationship between news providers and consumers. A stranded evacuee in St. Bernard Parish would text-message a relative on the East Coast asking to be rescued. That relative would post on the NOLA.com blog that their family was stranded. The NOLA.com blog staffer for the day would text-message a reporter in the field who might be embedded with the parish sheriff. The parish sheriff would text-message his crew at a post near the victim’s home to go in search (anyone with the New Orleans area code of 504 could not be contacted directly). When the evacuee was brought to the nearest shelter, a journalist there interviewed him or her to share the rescue story. Neither of them was aware of the web in which they participated in the creation of news and the relay of information. Before Katrina, journalists sought out stories, published or broadcasted them, and users occasionally posted feedback after the fact, and that was as much of a flow as there was between the two entities. Hurricane Katrina turned this structure on its head, forecasting a view of how information and news may be transmitted in a technology-driven century when local communications infrastructures flatline.

Hurricane Katrina showed us the importance of having diverse media for information distribution, but it also highlighted the diversity of those affected by disaster and their information needs.

This is the story of how the victims, the displaced, the evacuees—those affected by the crisis—used the media. For those around the nation and the globe who watched the natural disaster and its aftermath unfold, the use of media and its available technology was quite different from those users at ground zero whose needs for the media and its information were far more crucial to their decision-making and, in many cases, their survival.

Diverse Evacuees

The victims of Hurricane Katrina used all forms of media, both national and local, traditional and online in three main ways. Also, where they were situated as victims corresponded with how they sought out and used the news. Three main groups provide a window into these three media-use trends. Trend one we named “early responders” because they travelled the furthest away from the storm, and ended up relying on more remote news sources, such as national news and displaced local news outlets sharing simulcasts with subsidiaries in other southern states. We labeled trend two “caught in the middle” because they were the last group to evacuate moments before the storm hit and only made it as far as the closest city such as Baton Rouge, in the Louisiana case. This group relied on a mixture of media sources as they still had access to local media and national media in the region. The third group we named “caught in the storm.” For this group, media use resembled the spiderweb of information. Given a communication and technology blackout, this group was the most inventive in seeking, relaying, and transmitting information on the unfolding of the crisis in order to make life-saving decisions.

Weeks after Katrina hit, we tracked down approximately 250 residents living along the Louisiana/Mississippi state line to the New Orleans metropolitan area to tell us the stories of why the news mattered for them in this crisis, and how they accessed the news. Their experiences reinforced the argument that information and the jobs journalists hold as conveyors is vital in a disaster.1 A crisis like Katrina highlights the point that in an age of cynicism and supposed decline of the traditional press, media users in a disaster find that old-fashioned journalism is not outdated, yet. It may be adapted, but it remains vital.

Of the 250 Gulf Coast residents who told us their stories, 100 were “early responders,” 99 were “caught in the middle” and 51 were “caught in the storm.”2 A window into their evacuation narrative helps explain their media use trends in the Katrina crisis. “Early responders” to the crisis were the region’s professionals, business owners, public sector workers, and employees of major companies. They were the ones who could afford a week’s hotel stay in Houston, Atlanta, or Birmingham, and who had practiced evacuation drills implemented in their households, dusted and rolled out every hurricane season, once their local weather forecaster or mayor announced a voluntary evacuation. Katrina being a mandatory evacuation, this group was the first to make plans and leave the area.

About two-thirds of this group converged on Baton Rouge and its surrounding towns in the first two weeks. The rest relied on geography much further than the nearest city. Many fled to Houston and Dallas, Texas, others to the Florida panhandle, some to towns in northern Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. However, this was not a static group. Many moved several times across the Gulf Coast region in the aftermath of the storm as they strained their budgets staying at hotels they had only expected to hunker down in for a weekend and a few extra days.

The decision makers or heads of households of the “early responders” made the call for their families to leave the affected area before the storm, and then to return afterward. In the weeks and months after Katrina, once the city had reopened, roughly two-thirds of this group had returned, oftentimes with just one adult or part of the family, to live in outskirt towns of the New Orleans metropolitan area such as Kenner and in towns on the west bank of the Mississippi River that avoided flooding. Other “early responders,” about a third of them, commuted to their jobs from rentals and relatives’ homes in towns around Baton Rouge.

What informed the mobile lifestyle of this first group of evacuees was a shift in media use from a national account of the storm fed to them in hotel rooms to active search for local updates on the conditions in their area. Before the Katrina disaster, “early responders” overwhelmingly consumed local news reports on a weekly basis far more regularly than the other two groups at a rate of five to one. Local news helped them decide the best neighborhoods, where to send their kids to school, the state of the local economy, and which politician should have their vote.3 Partly due to age, ranging from twenty-five to sixty-one in our survey, also due to income, local television was their main information source as residents of the region. When there was a partial local news blackout in their remote evacuation locations, this prompted information seeking on their part for news that helped them decide whether to bring their families back to uncertain conditions in the weeks following the crisis.

The second group, those “caught in the middle,” are like the “early responders” in that over time they became active information seekers of local news content despite their quasi-remote locations camping on the outskirt towns of the city. Where they differ is in their demographics and prior media use before the crisis. We surveyed ninety-nine of those “caught in the middle,” who had evacuated a little more than an hour away to the Louisiana state capital, Baton Rouge, and sought shelter with friends, relatives, or even slept in their vehicles at the side of the road or in public buildings around the city. Many residents “caught in the middle” were late deciders, who in the last windows available to evacuate the areas in the eye of the storm made a quick dash to the nearest exit points and only made it as far as the next largest city, given the bottleneck traffic heading in all directions of Interstate 10.

Half of this group we found enrolled at Louisiana State University for the fall 2005 semester as “visiting students.” The state’s flagship university made special accommodations for such students from universities in the affected area that were forced to close their doors for the rest of the academic year. LSU made two dorms on the campus available to specifically house them once they arrived, opened special sections of core courses for them to gain standard credits for transfer once their colleges had reopened, and waived tuition and other enrollment requirements as many of these students had already paid tuition at New Orleans–area institutions. Why this group is unique is because unlike the “early responders” and those “caught in the storm” roughly half of this group were not native to the Gulf Coast region; many were out-of-state students and employees, such as professors. Therefore, local news was not their go-to source for information.

Despite offers from universities across the country, including Harvard, inviting students “caught in the middle” to attend the semester there, these students chose to attend the university closest to the affected area, LSU. A major factor in this decision was the information and narrative students “caught in the middle” gleaned from local news accounts about the affairs on the ground.4 This mostly young, ages eighteen to twenty-six years old, tech-savvy, Internet-using group had perhaps the most options to leave the crisis area and never return. The “early responders” and those “caught in the storm” had the most ties to the region—jobs, homes, and memories going back several generations of families—yet something prompted many “caught in the middle” Katrina evacuees to remain. Perhaps the information they received and shared during the crisis contributed to their decision to linger in the area longer than would be expected of them.

Finally, we found those “caught in the storm” to be of all age groups, but mostly of lower-income backgrounds. We found retirees, skilled laborers, the unemployed, single mothers, low-income families, and in some cases those overcoming addictions or mental and physical disabilities.5 A small 10 percent of them had finished high school, and an even smaller 2 percent had college degrees and were working in fields such as nursing and education.6 They rode out the storm, stayed behind to safeguard their homes, could not afford to evacuate, and in some cases told us that they had “rescued themselves.”

Those whom law enforcement and other relief crews rescued found themselves deposited at organized shelters such as the Baton Rouge River Center and faith-based shelters in Baton Rouge, such as one organized by Bethany World Prayer Center, a large evangelical church in the capital.

Those who “rescued themselves” tell of journeys in search of shelter where they waded and swam through water, losing loved ones to unknown suctions under their feet. Some broke into schools, headed toward police stations or parish government buildings and finally were told to go to the New Orleans Superdome or Convention Center. Once at these two notorious shelters there was endless waiting for supplies or information on their fate. A week into the aftermath they were moved to the Houston Astrodome awaiting a final destination. Many of them said they wanted to return to the state and took the first opportunity to be housed in one of the temporary Federal Emergency Management Authority (FEMA) trailer parks set up for evacuees on the outskirts of Baton Rouge. We were given official access to this group of evacuees at the FEMA trailer park in Baker, Louisiana. Again, this group had low income and education. Often, we had to read aloud the survey to them and write down their answers.

Their stories of escape and rescue shed light on what happened to those media users who experienced a complete blackout of information as the storm passed over and as they helplessly waited for word on their fates. They help us to understand the spiderweb of information relay that occurred in this crisis, and the power and need for the media in matters of life and death.

Media-Use Trends

“Early responders” used local news as a traditional news source, those “caught in the middle” used the Internet and national news, and those “caught in the storm” rarely used any media source consistently, before the Katrina disaster. Yet once nearly a million residents across the Gulf Coast got word that a major hurricane was coming their way, they told us that they all tuned in to local television news for information. The situation changed quickly in the days to come. Putting this volume of residents on the region’s interstates and highways for roughly three days of intense evacuation provided a logical media-use transition. Residents told us they had few options but to listen to the radio reports as they sat in their cars in the parking lot that Interstate 10 had become. However, this was not the typical top-of-the-hour radio news report cutting off their favorite pop tune. Some noted they tuned in to the radio signal many television stations still broadcast through, but seldom listened to. Others noted that many music format stations reaired or read local television and print news updates on the status of the approaching hurricane in longer news segments. For those placed at a dead stop on contra-flowed highways, or, as we will see later, left behind without power and becoming prisoners of accessibility, radio was their only lifeline.

Once evacuees reach their destinations, and the disaster is now in what crisis researchers call the “impact phase,” we begin to see a divergence of media use among the three main groups. Some of those “caught in the middle” tech-savvy users lost their 3G signal once the storm blacked out cell phone lines, and for the first time, Internet use drops in accessibility and influence behind television, radio, and even newspapers.

It is in the impact phase where we begin to see a new user habit. Evacuees, in general, acknowledge that national news accounts were most accessible, meaning they could see it or hear it in public or residential spaces with ease. However, they pointed out that they actively sought out alternative media accounts, particularly local news. They were active information seekers, texting relatives out of state to check the websites of local news outlets of their cities for specific updates and accounts. Some “caught in the middle” evacuees sat in their cars to pick up AM radio transmissions from the affected cities once power went out in outskirt areas from the impact zone of the storm. For those who did not have cell phones with a 504 area code, they recalled being able to use their phones, powered by car batteries, to call in to local news hotlines to find out about areas where loved ones were left behind. Others texted friends out of state to call in on their behalf, given the jam to area cell phone numbers.

The impact phase of the crisis started the spiderweb of communication and information-seeking that flourished in the aftermath of the crisis, once the storm had passed over, leaving its devastation behind. This media usage is significant, supporting studies of prior disasters where victims actively sought out local news accounts because their confidence rested in local journalists’ knowledge of their cities and conditions on the ground.7 Where Katrina is different is that the information flow is far more complicated by the inability to communicate, both on the part of journalists, as chapter 2 demonstrates, and on the part of victims. When the media cannot speak directly to its primary users, in this case Katrina victims, we find that the relationship remains unshaken. It is these users who now find creative ways, through friend and family networks across the country, outside of the disaster zone, whom they alert to local news sources, to channel information to them or back to them. It is this that gives Katrina unique information use in an age of technology and interactivity online, and one that shows up in other disasters with communications blackouts such as the 2010 earthquake disaster in Haiti.8

In the aftermath of the storm, media use broke down across the three groups. “Ea...